On the right, they denounce political correctness and the interference of the nanny-state. On the left, corporate cronyism and capitalism’s chosen ones, the ‘1%’, are the target of their ire. Might the success of populism’s class of 2016 owe a debt to our innate cognitive biases?

Aside from the untimely deaths of beloved actors and musicians, the rise of populist politicians – speaking truth to power and challenging the perceived political elites – has very much been 2016’s thing. In the UK, Nigel Farage’s successful campaign for a ‘leave’ vote in June’s referendum on ‘Brexit’ relied heavily on exhorting British citizens to “take back control”. Donald Trump collected the Republican nomination to run for President of the United States vowing to “Make America Great Again”, and has seen his poll deficit to Democratic candidate and stalwart of the American political establishment Hillary Clinton narrow in recent months. Honourable mentions must also go to Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders for their leftist take on the genre.

- Jeremy Corbyn

- Nigel Farage

- Bernie Sanders

Undoubtedly, there are geopolitical, economic and historical explanations for the trend. But, in amongst all the rationalising and reasoning around 2016’s populist success stories, there should be an awareness of how and why their messages resonate so resoundingly with people – and why now? Cognitive biases – characteristic patterns in the ways our brains cut corners when processing information from the outside world – may offer a partial explanation.

As a member of the EDIT lab, I think most about cognitive biases in terms of psychopathology. For example, previous work from our group has shown how attributional style – the tendency to attribute events to internal versus external, stable versus transient, and global versus local causes – is genetically related to both current and prospective depressive symptoms in adolescence. Similar results have also been found for interpersonal cognitive biases (‘perceptions and expectations of others and beliefs about oneself’), attentional biases to threat (sensitivity and bias in attending to environmental factors perceived as threatening) and anxiety sensitivity (the tendency to perceive anxiety-related cues as threatening or dangerous), among others.

“Understanding the biases that motivate us as democratic voters is worthwhile; not least, because you can bet that the politicians competing for our attention do”

One of the key aspects of our approach to the study of these cognitive biases is an assumption that they are, on the whole, continuous traits that are normally distributed within the population. This means that everyone’s cognition is biased in the kinds of ways described above, to a greater or lesser degree. For example, one individual could have a strong bias towards interpreting negative events as being caused by their own actions, and another a strong bias towards perceiving external causes – with most people falling somewhere in between. Indeed, the idea of biased cognition as ‘rule’ rather than ‘exception’ is not controversial; many famous examples exist (e.g., the Dunning-Kruger effect), and the issue of implicit biases has recently become a mainstream topic.

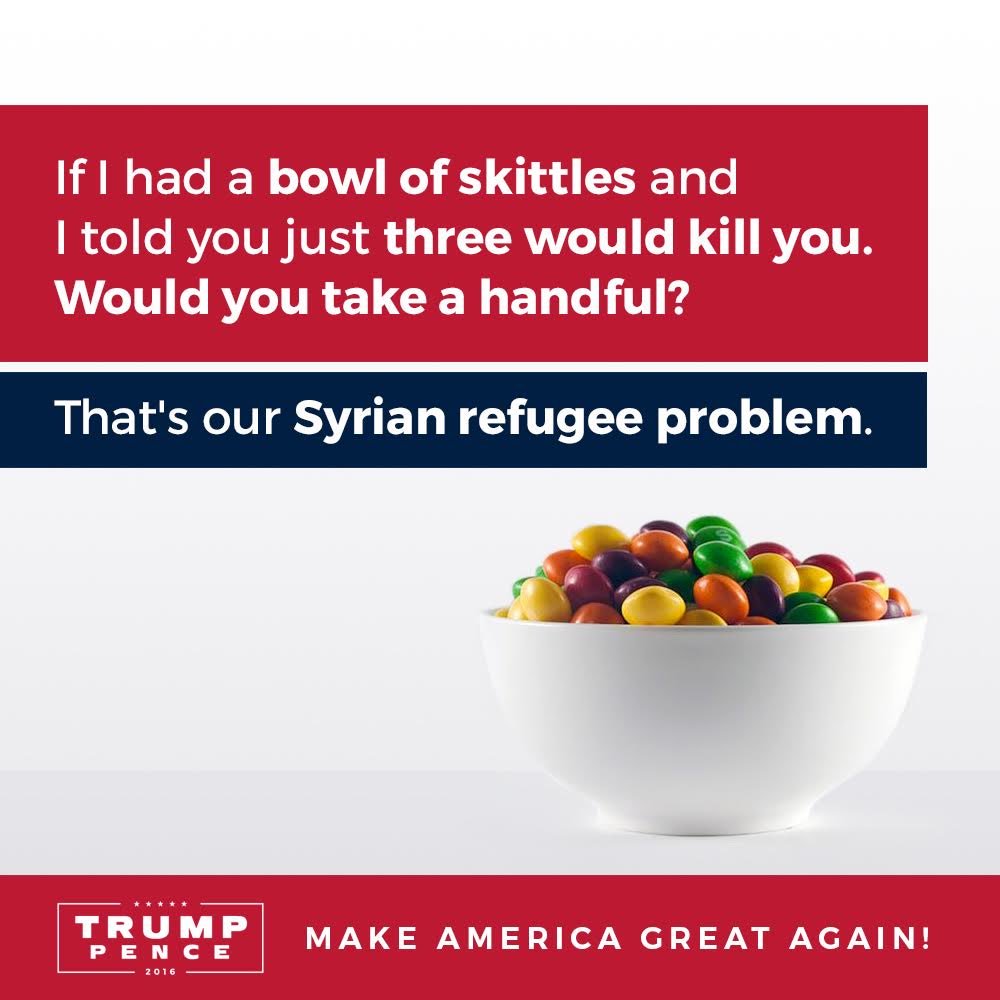

- Seeing threat where there is ambiguity? Donald Trump’s presentation of the ‘Syrian refugee problem’

As far as our cognitive biases are concerned, populist political messages may be music to our ears. Underlying all the specific biases listed above is our brains’ quest for simplicity where there is complexity. As a strategy for an individual human navigating a busy, noisy, messy, sometime dangerous world, heuristic rules to sort the semiotic wheat from the idiosyncratic chaff make perfect sense. However, the government of nations is, by definition, a complex business. Perhaps then, the route of the appeal of a populist political challenger – whether Corbyn or Trump – lies in their freedom to pit the simplicity we all crave, against a ‘political establishment’ entangled in the complexity of actually doing the job.

The point here is not that our cognitive biases are bad – but that they can be exploited. Understanding the biases that motivate us as democratic voters is worthwhile; not least, because you can bet that the politicians competing for our attention do. Whether the populist class of 2016 are able to turn their success at feeding our biases into the kind of political success that materially affects people’s lives remains to be seen.

In the meantime, at least some people are finding alternative uses for the characteristic communication style of populism’s poster-boy Trump:

We need a total and complete shutdown on methodological terrorists entering our journals, until we can figure out what the hell is going on.

— Stuart Ritchie (@StuartJRitchie) September 21, 2016

[…] made me think about Laurie’s excellent piece about cognitive biases and their role in the recent rise of populist politicians. He speaks about […]