By Susannah Hume, Zoe Claymore and Vanessa Todman |

The long–anticipated Augar Review was finally released last month, and raises many questions about the future of Higher Education (HE) funding. The review recommends, inter alia, a cut to the fee cap from £9250 to £7500; a reintroduction of means-tested maintenance grants, to replace the current loans system; and an increase and lengthening of repayments once the graduate is in employment.

Money Saving Expert has written a comment exploring in detail the financial impacts of this for students, so we won’t rehash it here, but Augar’s system manages to both look cheaper to prospective students and cost less to government. Depending on your perspective, this is either a neat bit of accounting or sludge that mostly impacts lower earning graduates.

However, with or without Augar, an important question is how to encourage students to make good decisions about HE, being mindful of what the financial costs and benefits are likely to be to them over the course of their lives. In this blog post we explore some of the ways that behavioural insights can help students consider the financial implications of going to university and make the right decision for them.

The nudges: how Augar’s recommendations reduce psychological barriers to study

Reflecting on Augar, our colleagues at the Behavioural Insights Team have blogged about the importance of how loans, fees and grants are framed, and note that cutting the headline fees may encourage more low-income learners to consider higher education. Likewise, returning maintenance grants could make university seem cheaper and more feasible. If we believe that going to university will benefit the individual financially over and above the higher repayments, then reducing the most salient figure is potentially a positive change.

Another behaviourally informed change proposed by the review is changing the discourse from ‘debt’ to a ‘student contribution system’. This also could be a positive change, as some research suggests students from disadvantaged backgrounds are particularly averse to acquiring debt to fund education. The discourse around the current student loans system has long been criticised for talking about student ‘debt’ when on a practical level it behaves quite differently to other forms of debt.

The sludge: the funding changes hide the sting in the tail – repaying more for longer

People struggle with processing financial information generally, and tend to prefer simpler information over more complex, and certainty over uncertainty, which helps explain the salience of the simple headline fee over the more complex repayment calculation. This is mainly problematic for the subset of students who might be enticed into choosing a low value degree when they should have considered other pathways (something Augar is quite elsewhere exercised about).

Further, behavioural research consistently suggests that people struggle to empathise with their future selves. Where this involves the disproportionate influence of costs and benefits in the immediate present over those in the future, it is known as present bias. For HE fees, the cost is in the future regardless of the fee regime; however, a subtle but important case of present bias may choosing to avoid the mental- and time-cost of reasoning through a complex decision like post-18 study, in favour of ‘going with your gut’. The costs or benefits of the choice are in the future, while the costs of the decision-making process are happening right now.

Helping students to make good financial decisions regarding university – whatever the fee regime

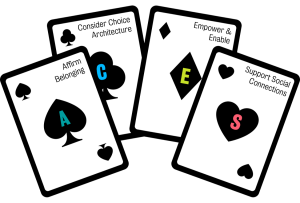

Ultimately, with or without the Augar reforms, our challenge is to provide financial information in a way that helps students engage with it and understand what the liabilities they are taking on now are likely to mean for them in the future. We use our ACES framework to think about how to use behavioural science to support students; ACES stands for Affirm Belonging, Consider the Choice Architecture, Empower and Enable, and Support Social Connections.

Below we outline some ways in which we think ACES can be applied to financial information provision; however, these approaches are speculative and would need to be evaluated in context before being implemented.

Affirm belonging

Making financial trade-offs is challenging, and for low-income students may be occurring in the context of broader worries about university and what it will be like for them. Experiential (‘hot’) information is equally, if not more, important to our decisions as factual (‘cold’) information. We can consider how to provide experiential financial information to students, such as using ambassadors, videos or testimonials by students from similar backgrounds, and giving financial information in the context of other aspects of university life. Knowing that others like them have navigated these decisions successfully and succeeded at university may free up mental bandwidth for thinking about financial trade-offs.

Consider the Choice Architecture

We can help people make optimal financial decisions and engage with quality information by making communications short and to the point. This information should include financial benefits as well as costs so students can estimate the differential between the average income of those who go into work straight from school and those who get a degree first. In addition, people find natural frequencies (1 in 5) easier to understand than percentages (20%).

A number of studies suggest the importance of personalised or semi-personalised information, rather than either providing generic information or expecting students to navigate to relevant information themselves. An example of this for the current student finance model is the Money Saving Expert student finance calculator, which focuses on repayments (the actual total amount of debt is never mentioned). Individuals can input potential loan amounts, along with projected earnings and it will provide them with estimates of their total repayments over the loan term.

Empower and enable

Financial self-efficacy is likely an important component of students’ propensity to engage in complex financial calculations: if a student has a sense that they are capable and competent at dealing with financial information, they are more likely to do so. Self-efficacy can be built up via direct experience or role models. We could get ambassadors to talk to prospective students about how they navigated the financial decisions, ask students to complete financial calculations that break things down into small steps, or encourage them to reflect on how they or their family have successfully managed other financial challenges.

An important factor in the level of present bias an individual displays is the extent to which they feel a sense of continuity between their current and future selves. Increasing students’ empathy with their future selves by, for example, getting them to write a message to the person they want to be, or to describe their ideal future life, may help to motivate them to more carefully weigh up the costs and benefits that will affect that future self.

We can also think about rendering costs and benefits to make it easier for young people to contextualise the impact on their future lifestyle of the need to repay their student loan. Breaking down incomings and outgoings to a level that is meaningful (for example, by weekly budget five years out from graduation, including other indicative outgoings) may help them to imagine the trade-offs. This could also be customised by asking students what is important to them; e.g. a meaningful job, opportunity to travel, lifestyle, building up savings, and so on, and tailoring the advice accordingly, and could be presented for several earnings scenarios, rather than just the average or median.

Support social connections

People’s social networks have a huge impact on their aspirations, expectations and opportunities. Research conducted by LKMCo for King’s suggests that parents are particularly concerned about the costs of university, and whether university will improve their children’s financial security in future. Working with parents and other influencers such as other family, friends and teachers, and considering how we can incorporate them into the approaches outlined above, is an important part of helping young people weigh up the costs and benefits of their post–18 options. For example, we are currently doing a project where we give parents information on HE subjects and pathways for their children (see our blog post on the trial for more info).

Helping students make the best decisions for them

Ultimately, making financial decisions can be challenging, and people find it very difficult to weigh up costs and benefits that occur at different time points, especially when there is uncertainty about some of those costs and benefits. Young people may find this doubly difficult because they have less experience managing money and may struggle to contextualise how much (or little) student loans will affect their adult lives.

Augar’s recommendations arguably make this calculation trickier, which could mean fewer students are deterred from beneficial university degrees because the real costs have become less salient to them. However, to the extent that we want students to be able to make informed choices about the best decision for them, we should be thinking – whatever the funding and fee environment – about how we can facilitate this.

Behavioural science suggests helpful ways we can help students to meaningfully engage with the information they are provided. Above, we have explored some possible directions for initiatives. However, its important to remember that people’s motivations and reactions to financial information can be complex and difficult to predict. It’s always important to understand why and how we think a particular initiative may work, and to design a robust evaluation strategy that takes account of the experiences of participants, and the context, alongside trying to understand the causal impact of the initiative.

Click here to join our mailing list.

Follow us on Twitter: @KCLWhatWorks

______________________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Behavioural Insights Team. (2015) Behavioural Insights and the Somerset Challenge. Available at: https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Somerset-Challenge-Report1.pdf, pg 16-26

Behavioural Insights Team. (2016) Moments of Choice. Available at: https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Moments-of-Choice-report.pdf.

Bettinger, E P; Long, B T., Oreopoulos, P & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2012). The role of application assistance and information in college decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(3), pp. 1205-1242

Costa, E. King, K. Dutta, R. and Algate, F. (2016) Applying behavioural insights to regulated markets Available at: http://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Applying-behavioural-insights-to-regulated-markets-final.pdf

Financial Conduct Authority (2017) From advert to action: behavioural insights into the advertising of financial products https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/occasional-papers/op17-26.pdf

Herbaut, E., and Geven, K. (2019) What Works to Reduce Inequalities in Higher Education? A Systematic Review of the (Quasi-) Experimental Literature on Outreach and Financial Aid , World Bank Group, Policy Research Working Paper 8802, Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/31497/WPS8802.pdf?sequence=4

Hershfield, H. E. (2011). Future self‐continuity: How conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1235(1), 30-43.

Kaiser, T. Menkhoff, L. (2017) Does Financial Education Impact Financial Literacy and Financial Behaviour and If so, When? The World Bank Economic Review, Volume 31, Issue 3 pp 611- 630 Available at: https://academic.oup.com/wber/article/31/3/611/4471971

Lim, H., Heckman, S., Montalto, C. P., & Letkiewicz, J. (2014). Financial stress, self-efficacy, and financial help-seeking behavior of college students. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 25(2), 148-160.

McGuigan, M., McNally, S., & Wyness, G. (2016). Student awareness of costs and benefits of educational decisions: Effects of an information campaign. Journal of Human Capital, 10(4), 482-519.

Money Advice Service, Behavioural Insights Team & Ipsos MORI (2018) A behavioural approach to managing money: Ideas and results from the Financial Capability Lab Available at: https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Financial-Capability-Lab-Report-May18.pdf

Oreopoulos, P. and R. Dunn, (2009), Information and College Access: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w18551.

Leave a Reply