“In order to keep up with the world of 2050…you will above all need to reinvent yourself again and again.”

Yuval Harari: 21 lessons for the 21st Century

“The future belongs to those who can reconnect with play.”

Rod Judkins: The Art of Creative Thinking

“Imagine inventing an education system that has the will to be creative as its core educational value and purpose.”

Emeritus Professor Norman Jackson, University of Surrey

Instructor: Dr Kieran O’Halloran

Email: kieran.o’halloran@kcl.ac.uk

Module: Film, Poetry, Style Level 5 https://www.kcl.ac.uk/abroad/module-options/film-poetry-style-1

Assessment activity: as part of an ethos of fostering creative thinking, students make a short film of a poem on a mobile phone. They use their analysis of the poem’s style to motivate creative choices in filming.

Why did you introduce a film poem assignment?

The need for creative thinking skills

Creative thinking and the practice of creating are fundamental to progress. Yet developing creative thinking has never been an explicit goal of higher education. More than ever, in the 21st century, this is needed. As environmental emergencies intensify—enormous problems specific to this century—as artificial intelligence rapidly penetrates the workplace performing tasks traditionally done by humans—the so-called ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ or ‘4IR’ (Schwab, 2016)—our students will need to be problem-solvers, change-makers and opportunity-generators in an unprecedentedly unpredictable and fast-paced world.

‘In the foreseeable future, low-risk jobs in terms of automation will be those that require social and creative skills; in particular, decision-making under uncertainty and the development of novel ideas.’

Karl Schwab (2016:40)

One key reason for creative thinking skilling is conjuring opportunities from unparalleled changes emanating from A.I. Moreover, for effective creative thinking in this fast-changing century, graduates should be adaptable (Penprase, 2018: 220). Encouragingly, alongside critical thinking, collaboration, communication, creativity is one of the ‘4Cs’ educational theorists increasingly promote for graduate flourishing in the 21st century (Davidson, 2017; Kivunja, 2014; Trilling, 2009). All these ‘soft skills’ are needed by employers, as well as the ‘hard skill’ of video-production (Fig.1).

Fig.1 Desirable skills in the contemporary workplace (LinkedIn Learning)

Fig.1 Desirable skills in the contemporary workplace (LinkedIn Learning)

Making and creative problem-solving

In subjects such as art and design, architecture, fashion and textiles, progressive development of students’ creativity happens by making new things. This occurs too in STEM “makerspaces” (science, technology, engineering, mathematics). Constructing novel stuff—whether digital or non-digital—practises and hones inventive problem-solving, in turn extending inventive thinking capabilities. Assignments that involve making new things have not, however, been the norm in humanities teaching. A focus on (collaborative) making in the humanities, with the byproduct of extending inventive problem-solving capabilities, helps students develop confidently creative self-images for a future they will have to continually adapt to.

On Film, Poetry, Style, videoing a poem is a new form of problem-solving for students (how to realise successfully a cinematic vision for a video of a poem, where best to shoot, how to employ actors effectively, how best to use backgrounds to communicate symbolically etc):

‘A big part of a director’s job is problem-solving—and doing it on the spot. You need to make decisions quickly and wisely, because not making a decision is a decision.’

(Stoller, 2019: 244).

Adapting to and solving problems within an unfamiliar digital arts practice leads to new creative resources being released. The module has been designed to be accessible to any student in higher education, not just in English Studies—no previous experience of filmmaking or analysing poetry being required (see below ‘Humanities Creative Thinking as Generic Skilling’).

Risky-ready versus risk-averse students

Understandably given the expense, many students see university education as attaining a good degree for realising job opportunities. This can lead, however, to a risk-averse mindset. Why experiment (too much) in an assignment if this leads to failure and a bad grade? Far better to reproduce the assignment models provided by the lecturer. While such risk-averseness is understandable for the short-term goal of a good degree, it can mean students leave higher education without confidently creative self-images. It is important, then, that pedagogies encourage ‘risk-ready’ mindsets (Watts and Blessinger, 2017). Film, Poetry, Style gives credit for boldness of vision, incentivising through its marking scheme (see below) students to experiment and take chances.

What is a film poem?

A film poem is simply a film of a poem, often a canonical one (Blake, Dickinson etc). While the genre is around as old as film itself, as digital innovation makes film-making easier, there has been a surge in film poems in recent years. A key feature of a film poem is ‘mashup’ of unrelated visual images with the poem, activating fresh meanings in it. This means a film poem usually exceeds standard perceptions of what the poet intended, becoming a new artwork. One creative work is used as a springboard for another. (For many examples of film poems, see Movingpoems.com).

Integral to the imaginative process is making new and unusual connections:

‘Creativity is that marvelous capacity to grasp mutually distinct realities and draw a spark from their juxtaposition.’

Max Ernst

Since they involve unusual connections between film and poem, making film poems is ideal for fostering creative thinking. Film, Poetry, Style expects students to make surprising and imaginative connections between their movie and the source poem.

The module, however, goes beyond what is standard in the film poem genre in requiring that students make a secondary set of connections: identifying foregrounded features of style in the poem and using these to motivate creative choices in filming. (Analysis of a poem’s stylistic foregrounding doesn’t happen in the film poem genre as a rule where, overwhelmingly, the emphasis is making the film). The student utilises understanding of the poet’s creativity to extend their own.

Illustration: a student film

I come to a student film of a Charles Bukowski poem, “the bluebird” (Bukowski, 2010). In this five stanza poem (46 lines; 191 words), the poem’s persona uses the bluebird as a metaphor for something they keep hidden since its escape could lead to difficulties.

Here is a film of “the bluebird” made by former students Jasmine Bastable and Courtnay Osborne-Walker.

In line with the film-poem genre, Courtnay and Jasmine created a cinematic vision that goes beyond, more than likely, what Bukowski intended. In the students’ cinematic vision, the poem’s persona is fleshed out as a young man, with the bluebird his hidden homosexuality. Moreover, this is a good illustration of how quite simple features of a poem’s style, in this case personal pronouns, can be used to motivate creative choices in filming.

Click for short explanation (PowerPoint slides) of how changes in personal pronouns (‘I’, ‘you’, ‘he’) across the five stanzas correlate with different shot choices in the film: Short explanation

Click for a longer (prose) explanation of the same: LONGER_EXPLANATION

Click for the film’s shot list: Shot_list_the_bluebird

How did you design the assessment criteria and weighting?

The assignment has three components:

(A) short film (at least 1 minute);

(B) 500-1000 word shot list in note form together with how stylistic features motivated creativity;

(C) 2,500-word report: analysis of poem’s style plus explanation of how analysis motivates creative choices in film.

Since a key focus of the module is developing creative thinking, the assignment balances marks for creative ideas in the film with analysis of the poem’s style:

50% for creativity of film plus clear and convincing explanation of how creative choices are motivated by analysis of the poem’s style;

50% for accurately analysing prominent features of the poem’s style.

Students are expected to create a “working shot list” in the first instance, in order to plan their shooting. Otherwise, filming is too open and time inefficient. Yet things in the filming environment will occur spontaneously to the students to use inventively for their film (“creative connection-making 1”). What students submit for Part B is the “final shot list”, a note-form final written record of their edited video and how the poem’s prominent stylistic features motivated creativity (“creative connection-making 2”).

Part B and Part C are done individually or in a pair. Even if Parts B and C are individually produced, Part A—making the film—involves collaboration. The module develops this other 4C skill by students acting in each other’s films, working as alternative camera operators etc. Indeed, it is in the interests of the student director(s) to employ other camera operators whose footage can provide surprisingly creative possibilities for the video. More generally, student collaborators can offer ideas for problem-solving in filming the poem. The student director(s) is expected to exercise critical thinking (another 4C skill), too, in selecting the most effective ideas to build on.

A gorgeous and technically arresting videoed poem is unlikely without sustained film production training. While beautiful films are welcomed, the pedagogy emphasises inclusivity. So the film poem’s artistic quality is not evaluated. That said, sound—including voice-over—in the video should be audible; lighting too should be sufficient for the viewer to see it. And, in line with any passable film, students are expected to use a variety of camera shots (e.g. close-up, mid-shot, long shot) to stimulate viewer interest. Lastly, in allowing students to experiment with video production, the module provides a useful platform for further developing this increasingly desirable ‘hard skill’ in the workplace.

How do you introduce the assessment to students?

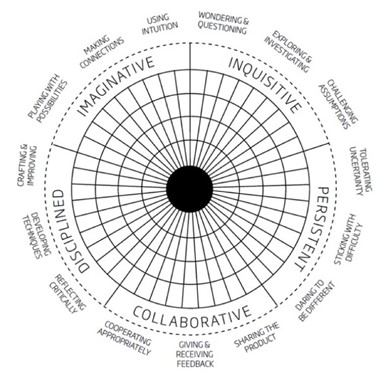

From Week 1, students know they are expected to make a creative film of a poem of their choosing. To this end, I flag a variety of aids for creative thinking from the start, e.g., the “creativity wheel” (Fig.2) devised by Bill Lucas and Ellen Spencer from their book “Teaching Creative Thinking” (Lucas and Spencer, 2017). This helps students become keenly aware of key creative thinking processes for enhancing film design.

Fig.2 “Creativity Wheel” from Lucas and Spencer (2017)

Students receive not only a detailed study guide but an assignment guide also.

Throughout the module, there is plenty of modelling of the summative assignment. Students are shown examples of previous student film poems (in the public domain or I have permission to show). Moreover, in Weeks 1-7, I model stylistic analysis of poetry, using different poems each week.

The module being inclusive, students are assured there is no expenditure for their summative assignment. The video camera quality of contemporary mobile phones—which they all own—is very good, and there are numerous free apps for editing and enhancing (effects, colour grading etc) their film, e.g. Apple’s iMovie and Capcut.

How do you give feedback?

- Formative assessment

It is important students practise making a film poem before the summative assignment. (I have yet to encounter a student who has created a film poem before). After the Week 5 teaching session, they do this in groups of three, honing collaborative skills in the process. Crucially, students make films of poems whose stylistic analysis I have already modelled. That way, they can just concentrate on practising filmmaking. I stress for this practice film, as for the summative assignment, they need one clear simple concept.

In the Week 8 session, students show their practice films on the teaching room screen and I/we feedback constructively, sharing ideas for enhancing creativity. With teaching room seating in theatre setting, Week 8 is normally fun—a bit like going to the movies.

With guidance, students use the module marking criteria (see below) to give each other feedback, helping them understand concretely how their summative assignment will be assessed.

The Week 8 session also addresses common issues:

- Being exposed to practice films made by risk-ready peers helps motivate risk-averse students to be bolder at summative assignment;

- Students can appreciate viscerally—when receiving puzzled reactions from peers to an overly elaborate idea—that simplicity is important for a short film poem;

- Key to audience understanding are establishment shots at the beginning of a film, drawing the viewer in, establishing what the film is about. In a film poem, they usually occur before the poem’s lines. I/we comment on the effectiveness of establishment shots.

This advice and other suggestions are also provided in the study guide.

- Individual consultations

Weeks 9 and 10 are devoted to individual consultations. By this time, students are meant to have cinematic ideas for at least three poems. I indicate where poems are too long or too short for a film of at least a minute. (While word count is not normally a useful guide to a poem’s complexity, a poem beyond 300 words will likely be too long to do justice to in a short film). I ask students to summarise their film concepts in 10 words or less, the consultation continuing to thwart unclear/overly elaborate film concepts. Together we discuss which poem would work best cinematically, though the poems students film are ultimately their choice.

I provide one last encouragement to ‘dare to be different’, while flagging that students should not compromise safety in filmmaking or produce/use illegal, obscene, or culturally insensitive images.

- Summative feedback

Students submit their assignment to Turnitin on KEATS—around 6 weeks after the module finishes. Written feedback is provided when marking in the usual way.

What benefits did you see?

For students:

- Students appreciate the space to be creative, e.g.:

‘The module ‘Film, Poetry, Style’ permitted freedom and creativity unusual in King’s. This innovative way of exploiting analysis of style in poetry in film really excited me and challenged my approach to analysing literature and language in general.’

(Scarlette Isaac, undergraduate)

‘I really enjoyed making creative connections in filming poems as it stretched my inventive thinking. The module also motivated me to learn how to better use video editing apps. I now have a part-time job where I am able to practically use the creative editing techniques introduced to me on the module.’

(Charis Nash, undergraduate)

‘The whole concept of combining filmmaking and poetry has allowed me to develop creative and problem-solving skills—useful transferable abilities for future employability.’

(Gaynor Wells, undergraduate)

- Generally, summative assignment films have had bold creative visions. The module has had success in encouraging a “risk-ready” mindset, and thus development of a personal capability essential to being creative;

- Many students have been non-UK nationals, completing summative assignments in their home countries during vacations, their films including shots of national environments, e.g. India, Lebanon, South Korea, Spain, USA. This has, inadvertently, afforded a saliently visible global dimension to the module.

For me: it’s very rewarding to teach a creative pedagogy, to view highly imaginative work, to appreciate I have played a role in students developing their creativity, and to see that video-based assignments are ideal for immediately reflecting King’s diverse international student body.

What challenges did you encounter and how did you address them?

- Some students can be anxious about the novelty of making a video. Aside from support already mentioned, all students are expected to follow tutorials on LinkedIn Learning for mobile phone filmmaking after teaching sessions;

- To assist students in producing their movie, they are made aware of extensive free filmmaking resources (on the web), including sound effects, editing/ enhancing apps, as well as creative commons video resources to be used where too difficult to film;

- To achieve more stable footage, students can use ‘smartphone rigs’ (sourced from our departmental budget)—simple rectangular frames with handles either side, and a clamp for holding the mobile phone steady;

- Should students not enjoy filming, they can use animation apps instead for making their film poem;

- Creative thinking is not usually foregrounded in university-wide marking criteria. Where ‘originality’ is flagged, this is usually in the first-class band only. In contrast, a curriculum permeated by invention needs to accommodate different degrees of creative thinking from pass onwards. The module-specific assessment criteria meet this need: Module_SPECIFIC_MARKING_Criteria_Film, Poetry, Style

What advice would you give colleagues who are thinking of trying a creative digital making pedagogy / visual assessment for learning?

- This does not necessarily mean generating a new module—merely tweaking current pedagogy/ assignments. Consider, for example, a Media Studies assignment where students critically analyse an advert’s iniquitous political angle. They could also ameliorate the advert through digital re-design, employing umpteen freely available apps/apps carrying free functions;

- If a student is expected to make a short video (1-3 minutes), they only need rudimentary knowledge of film grammar and basic skills of shooting and video-editing. All students on ‘Film, Poetry, Style’ have been able to acquire such knowledge/skills. Since some may, initially, be apprehensive about the novelty of filmmaking, it is important to stress they are not striving for video masterpieces. Educators don’t expect even first-class students to write essays to the standard of George Orwell or Virginia Woolf! So, we can hardly expect such unrealistic standards in students’ videos;

- Young people are creating short films for social media. Video-making for assessment is an extension of what many students do already. Yet there will be those new to filmmaking. Advisable then to build in formative assessment where students make a practice video in a group, helping each other grasp the process (see above);

- A handy way of learning to make a short film is the ‘trailer option’ in iMovie app: making trailers for a ‘Hollywood movie’ in different genres (horror, romance etc), with the filmmaker prompted to load up a variety of shots—long, mid, closeup etc. No technical knowledge is needed, only a cinematic idea, making this an accessible way of learning filmmaking ‘on the job’;

- With rich software resources available to students—video editing apps, YouTube creative commons footage, mobile phone filmmaking tutorials on LinkedIn Learning etc—myriad possibilities exist for instituting video-based pedagogy/assessment where much learning can occur outside teacher-student contact time.

Humanities Creative Thinking as Generic Skilling

Recent research shows that the creative process in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) is very similar to that in the arts. A holistic approach in higher education makes sense for teaching creative thinking—especially given need for inventive adaptability not just in 4IR but 21st-century existence generally. Humanities subjects can contribute to this need by offering accessible modules across a university for developing creative adaptation. These humanities modules would instill interdisciplinary thinking and 21st-century (4C) cognitive skills, fostering new modes of collaborative problem-solving through making unfamiliar things, digital and/or non-digital. In turn, untapped imaginative resources are released, and cognitive flexibility is continually exercised with students’ self-images as creative and adaptable thinkers becoming increasingly confident. Team-based problem-solving and communication skills are augmented also.

Echoing earlier, Film, Poetry, Style has been designed to be accessible to students outside English Studies with no previous experience in filmmaking or analysing poetry. It encapsulates this humanities vision for developing holistic and adaptive creative thinking capacities and other 4C skills necessary for 21st-century graduates.

To read more about Kieran’s research on this creative pedagogy, see:

O’Halloran, K.A. (2023) ‘Posthumanist stylistics’, Language and Literature 32(1): 129-162.

Bibliography

Bukowski, C. (2010) ‘the bluebird’. In Charles Bukowski, The Pleasures of the Damned: Poems, 1951-1993 (edited by John Martin), Canongate: Edinburgh, pp. 494-495.

Davidson, C. (2017) The New Education, New York: Basic Books.

Harari, Y. (2018) 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, London: Jonathan Cape.

Jackson, N. (2017) ‘Foreword’. In Watts, L. and Blessinger, P. (eds.) (2017) Creative Learning in Higher Education, Abingdon: Routledge. pp.ix-xiv.

Kivunja, C. (2014) ‘Innovative Pedagogies in Higher Education to Become Effective Teachers of 21st Century Skills’, International Journal of Higher Education 3(4): 37-48.

Lucas, B. and Spencer, E. (2017) Teaching Creative Thinking, Carmarthen: Crown House Publishing.

Penprase, B. (2018) ‘The Fourth Industrial Revolution and Higher Education’. In. N.Gleason (ed.) Higher Education in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Palgrave MacMillan, pp.207-229.

Schwab, K. (2016) The Fourth Industrial Revolution, Crown Business: New York.

Stoller, B. (2019) Filmmaking For Dummies, 3rd ed., Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Trilling, B. (2009) 21st Century Skills, San Francisco: Jossey Books.

Watts, L. and Blessinger, P. (2017) ‘The Future of creative learning’. In Watts, L. and Blessinger, P. (eds.) (2017) Creative Learning in Higher Education: International Perspectives and Approaches, Abingdon: Routledge, pp.213-230.

For an excellent set of resources for stimulating creative thinking and practices in Higher Education, see: https://www.creativeacademic.uk/ curated by the educationalist, Professor Norman Jackson.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Professor Bill Lucas for allowing reproduction of the ‘Creativity Wheel’.

Leave a Reply