Instructor: Dr Laura Gibson with Mariam Ghorbannejad (Learning Developer at King’s Academy)

Contact: laura.gibson@kcl.ac.uk and mariam.2.ghorbannejad@kcl.ac.uk

Module: MA in Digital Asset and Media Management programme in the Department of Digital Humanities (DDH).

Assessment Activity: as part of an Arts and Humanities Education Fund project, we have undertaken this research on how providing different types of feedback (written, audio, and audio-visual) to students improves their learning and take up of feedback.

Why did you conduct this research into different types of feedback?

The MA in Digital Asset and Media Management (DAMM) regularly has an annual cohort of more than 100 students. These students come from diverse educational and disciplinary backgrounds. For most, this is their first experience of university in the UK and of producing HE-level English language assessments. While DDH academic teaching staff are committed to assessment for learning—whereby students have opportunities to learn from lower-stakes, confidence building exercises and receive feedforward on these (Sambell, McDowell & Montgomery, 2013)—the realities of such large cohorts and understaffing means giving meaningful feedback on assessments is a daunting task.

Group work can potentially reduce the quantity of feedback required from assessors, but the challenge is ensuring that it still delivers high-quality information to individual students about their learning (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006) so that they can use it to improve their work or learning strategies (Carless & Boud, 2018). We’re interested in how we can innovate the format in which feedback is delivered so that it benefits both staff and students, and wanted to research realistic possibilities for overcoming some of the staffing challenges associated with continuous assessment within large cohorts.

Mariam and I designed this research project around two student workshops to explore more specifically how different forms of group feedback affect how students engage with, and then apply, group feedback to their individual work. For this project, we experimented with three types of feedback:

- written,

- audio,

- audio-visual.

How did you set it up?

| Workshop | Date | The workshop content |

1 |

Early May 2023 | A scaffolded synthesis task to identify key features and qualities

Students were divided into three groups to discuss 4 extracts on the impact of ChatGPT-4 Students produced a 200-word synthesis using the extracts in 20 minutes Students then produced a Concept map (link) in class using A1 sheets and pens in response to the question: How can we rethink HE assessments in the age of ChatGPT?” |

| The Feedback Stage

– Students work was marked using the standard College PGT marking criteria

-all groups were given 3 areas of strength and 3 areas for improvement |

Two weeks between 1 and 2 | Each of the three groups was assigned a mode of feedback at random:

Group 1- written on MS word doc Group 2- audio using voice notes Group 3- audio-visual using Kaltura Quick Capture on 3 animated slides Students did not know which one they would receive. |

2 |

Mid may 2023 | We went through the PGT marking criteria with students

Each group had time to review and discuss the feedback given and to write clarification questions 45 mins to write a 300-word written response to the same questions as in workshop 1 Evaluation discussion to reflect on the types of feedback given as well as in other modules. |

What other considerations did you make about the feedback?

- For the Audio Feedback: I wanted to recreate a more realistic feedback environment where I’d be under time pressure to complete the marking and so, while I made a few notes that I referred to as I recorded, I resisted the temptation to first write my feedback in full or to re-record the audio to make it smoother.

- For the Audio-Visual Feedback: I used different colours and symbols to underline sections of the text and highlight elements of the concept maps to emphasise the points to which I was referring in the audio. Again, I deliberately recorded the video in just one take.

- The depth and quantity of feedback that I gave each group was similar. However, in terms of how long it took to produce the different forms after assessing the tasks, the audio feedback took the least amount of time (approx. 10 mins) and the audio-visual took the most (approx. 60 mins). I emailed the students the feedback file for their consideration a few days before the second workshop.

What were your key findings and recommendations from this research?

- Students’ experience of feedback on their MA was primarily written

- They were largely disappointed with previous feedback experiences

- Yet, students still want their feedback to be written (most of the time).

- Students did identify some advantages of audio and audio-visual feedback as well as drawbacks

- The mode of feedback does not impact on students’ ability to apply it

- Students are more interested in content and frequency of feedback than the mode

The results are presented in detail below:

- Students’ experience of feedback prior to the workshop was primarily written

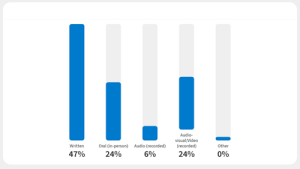

Figure 1: Results for PollEverywhere, “What forms of feedback have you received on assessments during your MA degrees at King’s?”

Figure 1: Results for PollEverywhere, “What forms of feedback have you received on assessments during your MA degrees at King’s?”

Some students selected oral feedback when completing the Poll, but during the discussion, most stated that they received this in addition to the written feedback once they’d made an appointment with their Lecturer after receiving their grade. Those students who polled audio-visual feedback all confirmed that they had received this feedback from me for a formative assessment on the MA DAMM core module.

- Their experience of previous written feedback was largely disappointing.

Students shared the opinion that the written feedback they’d received during their MA was “too short and too general.” Elsewhere, Reddy et al. (2015) have noted that if feedback is nonspecific, it can be a major barrier to students receiving effective feedback. One student expanded further on this point to explain that when reading the feedback, they have “the impression that the marker selected a few key points. It’s not that it’s not precise. But I feel like…there are other areas in my work that I could’ve got feedback on.” One explanation for this might be that markers are highlighting key points that evidence how the student’s work aligns with the PGT Marking Criteria and so justifies the final grade. Winstone et al., in their 2017 study into how university students receive feedback, suggest, however, that feedback focussed on a student’s performance relative to grading criteria is far less effective than feedback focussed on a student’s individual performance.

Another student reported that the length and depth of the feedback they received made them “feel like the markers have not really looked into [their] essays…they didn’t really spend time on it.” The group expressed frustration that the length of the feedback did not acknowledge or match the level of effort the students had put into their assessments.

Students were, however, very understanding about why their feedback might not be as long or specific as they would like, recognising that, “our tutors need to handle our many, many essays” and that it is not always their tutors assessing the assignments.

- Yet, students still want their feedback to be written (most of the time).

Despite the limitations of the written feedback received previously by students and despite being exposed to different forms of feedback in the workshops, students still stated a preference for written feedback over other forms in future. This was based on a feeling that written feedback is “more mobile” and so they “can read it on the tube, on the bus, everywhere.” They can also read it in their own time and at their own speed, as opposed to audio or audio-visual feedback that requires them to set aside a specific amount of time to listen to or watch the feedback and to follow at the pace of the speaker/marker. Students also remarked that it is easier to return to points in the written feedback as they don’t need to “rewind” a file and spend time finding where the point is being made.

- Students did identify some advantages of audio and audio-visual feedback despite highlighting several drawbacks of these forms of feedback.

While some students complained that the audio feedback was “too long” and so they “lost focus,” they rejected the suggestion that it be shorter because, “if the audio is more condensed then maybe the professor needs to cut the points.” They also commented on how, with audio, “it’s really easy to miss things” but shared that this was the case regardless of whether the audio was in their home language or English. However, the students did appreciate the tone of the audio, because “it’s just like talking to teachers. It feels more friendly.” They noted that the variety of tone in the feedback also helped them identify which parts of the feedback were more significant than others and which areas of improvement they should prioritise, which is less obvious in written feedback.

Students were more positive overall about the audio-visual feedback form. One student commented on how the combination of visuals and audio helped them understand what their Lecturer thinks is good about their work, and what needs improving. This student really liked a visual that underlined an example in the text related to the point being made concurrently in the audio; however, another student suggested that Turnitin’s in-text comments feature might achieve the same results in purely written feedback. A very honest student shared that they would actually pay more attention to audio-visual feedback over written because,

“I know the audiovisual will take more effort from the professor, so I will take more time to look over it, over it again…But for written, maybe I skip some sentences, and I’m not quite [as] careful with the written.”

This statement reiterates other points made by students about wanting the feedback to reflect a level of effort appropriate to the amount of effort they devoted to their assessments.

One aspect of both audio and audio-visual feedback that this particular cohort emphasised as beneficial is that they exercise and improve their English language listening skills. Students diverged, however, over whether this helped them retain or lose focus.

- Students are capable of implementing feedback given in all of the different forms.

Despite highlighting challenges with the audio and audio-visual forms of feedback, when we compared the final individual written responses with the feedback groups received on their synthesis and concept map tasks, we saw that students had clearly understood and applied the feedback received. For example, one area of improvement proposed to students in the audio feedback was to use convergence language to identify similar ideas more clearly, which these students then did in their individual tasks. This group was also praised for incorporating their own voice in the group tasks, and they continued to do this in their individual written contributions. The students who received audio-visual feedback on their group tasks were advised to make better use of citations to support their ideas and they implemented this advice very well in their final task. Likewise, the group that received written feedback all acted on the suggested areas of improvement in their subsequent individual responses, specifically using citations to make more general statements credible, using appropriate language to signal a shift in their argument, and concluding their piece with a summary sentence in their own voice, which each student did effectively.

We recognise that the students attending the workshops are likely the more diligent ones in the cohort and so spent more time than other students might in overcoming some of perceived challenges of the audio or audio-visual form to understand the feedback and then implement it. However, the fact that students were able to apply feedback given in all forms does suggest that the perceived problems with the audio and audio-visual are not insurmountable and these forms can be effective, especially if students become more familiar with them.

- Regardless of the form of feedback, students want more meaningful feedback, more often.

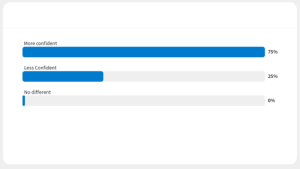

This became very clear during the evaluation discussion, particularly after students responded to a Poll about whether the feedback they received on their group tasks made them feel more or less confident about tackling the individual writing task.

Figure 2: Results for PollEverywhere, “Thinking about the feedback you received during THIS workshop, how confident did it make you feel about going into the individual writing task?”

Figure 2: Results for PollEverywhere, “Thinking about the feedback you received during THIS workshop, how confident did it make you feel about going into the individual writing task?”

A student who responded “Less Confident” shared that the feedback received on the group workshop tasks was their “first time to receive a very specific and long feedback. And so, I feel like I clearly see my problems…so I will feel less confident.” Yet, they acknowledged that:

“If I can receive [feedback] another time, maybe for a second time, I feel like maybe I will be more confident because I have a chance to write again…I should get used to this kind of feedback and get used to keep revising my writing.”

Another student reinforced this sentiment when she shared her positive experience receiving continuous feedback during a summer school in the USA:

“Every time we were coming into class, we were getting feedback from the previous class. I made such progress. Absolutely incredible…I stayed up. Because I was getting constant feedback. And I was able to every day, like, apply and improve.”

As Carless and Boud (2018) point out, students and teachers do misconceive feedback simply as comments on pieces of work, rather than a meaningful process of co-constructing standards, and so more comments on work are not equivalent to better feedback. Effective feedback does need to be meaningful in the ways discussed during this workshop—accessible and sufficiently detailed, yet applicable elsewhere—to be effective but there does still seem to be value in giving formal feedback more frequently in terms of increasing student engagement with it, increasing their confidence, and enhancing their ability to apply feedback effectively.

What challenges did you encounter, and how have you addressed them?

We planned the project for a group of 24 students and, with kind assistance from the A&H Student Experience Team managed to attract 28 students to sign up for both workshops. The funding allowed us to offer students refreshments, lunch, and a voucher as incentives to participate.

However, only 12 students actually turned up for the first workshop, which meant we divided students into just three groups, rather than the planned six groups. Consequently, we only had one group receiving each type of feedback and so our sample size is far smaller than we either hoped or anticipated. One benefit, however, of the smaller group size was hearing from every student during the evaluation session, which potentially allows us to gather a greater depth of opinions on forms of feedback. Even with the full planned-for cohort present, the sample size of 24 would be too small to really offer conclusive recommendations to improve feedback, but we do believe these findings are worthy of further investigation.

What are your next steps?

- I plan to integrate all three forms of feedback for group work into the core modules that I will run as part of the MA DAMM in 2023/24 since all have the potential to be effective. However, I will spend time in the lecture and seminars introducing the different forms to the students beforehand and will also devote time in subsequent lectures and seminars for students to ask more questions about the feedback, as we did at the start of Workshop 2.

- Based on the evaluation discussion, I plan to share the transcript of my audio and audio-visual feedbacks with the students as well as the sound and video files with the hope that this overcomes some of the accessibility challenges this cohort raised without increasing the marker’s workload further.

- I have also designed a series of groupwork formative assessments that more directly scaffold the final assignment so that students have greater opportunities to practise implementing the feedback they receive in different forms.

- Beyond making changes to the forms and frequency of feedback given in individual modules, the research does suggest we need a wider, Faculty-level discussion about how we can make sure students feel the feedback acknowledges and reflects the effort they have put into their assessments. This feeds into wider discussions about workloads, portfolio assessments, and student numbers.

References:

-

Carless, David, and David Boud. (2018). “The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, May, 1315–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

-

Nicol, D. J., & D. Macfarlane‐Dick. (2006). Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218.https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

-

Reddy, S. T., M. H. Zegarek, H. B. Fromme, M. S. Ryan, S. A. Schumann, & I. B. Harris. (2015). Barriers and Facilitators to Effective Feedback: A Qualitative Analysis of Data From Multispecialty Resident Focus Groups. Journal of graduate medical education, 7(2), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00461.1

-

Sambell, Kay, Liz McDowell, and Catherine Montgomery. (2013). Assessment for learning in higher education. New York, NY: Routledge.

-

University of Wollongong Australia (UOW). (2023) Concept mapping. https://www.uow.edu.au/student/learning-co-op/effective-studying/concept-mapping/ (Accessed 24 July 2023

-

Winstone, N E., Robert A. Nash, James Rowntree & Michael Parker (2017) ‘It’d be useful, but I wouldn’t use it’: barriers to university students’ feedback seeking and recipience, Studies in Higher Education, 42:11, 2026-2041, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032

Leave a Reply