Instructors: Dr Jamie Murdoch, Dr Lisa McDermott, Professor Seeromanie Harding

Email: Jamie.murdoch@kcl.ac.uk

Module: Health Improvement and Promotion, Master of Public Health, level 7 (FoLSM)

Assessment activity: Students are given a series of scaffolded formative opportunities working in groups to prepare for their summative submission of a poster for 40% of the module weighting.

Why did you introduce the formative assessment?

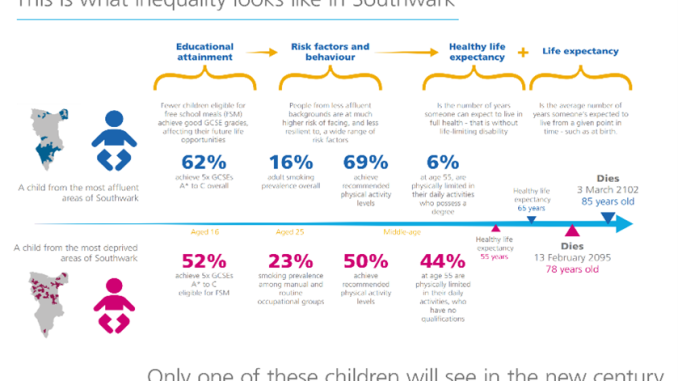

On the Health Promotion and Improvement module for the Master of Public Health (MPH), students are asked to design a poster for 40% of their summative assessment. The poster needs to illustrate a) the determinants of a specific health inequality amongst adolescents in London boroughs, and b) the design of an intervention to readdress this inequality. Students also provide a 1000 word critical reflection on the process of designing their specific intervention. Students are given lectures from guest speakers and academics and expected to apply the theory around conceptual models of health inequality determinants to a specific area of their choice.

Students’ feedback from the previous semester on the assessment made it clear that they did not fully understand the nature of the assessment, especially in relation to the learning outcomes of the module and how the activities that had been introduced in the seminar (largely discussion based) helped them prepare for the assessment. This seemed to be more of a problem with the preparation than of the assessment itself, which we felt helped students to apply the theory learned in a practical way and assessed critical thinking higher order skills. Therefore, we decided to redesign the seminar activities to make more coherent links between formative activities and summative assessment.

From our experience in previous years, both on this and other modules, we also noticed that there was mixed engagement within seminars, and some of the activities did not seem to be fostering an inclusive learning environment. There was a mix of dominant students and silent ones. We were keen to help ALL students engage in a way that best suited them but encouraged active participation (Tanner, 2013). We were also influenced by Krathwohl’s (2002) adaptation of Bloom’s taxonomy, on acquiring and applying critical (a key requirement at Master’s level) and creative thinking. The best way to do this was through designing active learning activities which were not only inclusive but helped them to develop critical thinking skills in a scaffolded way (Brame, 2016).

Finally, we were keen as educators to develop our own skills and try out new methods of teaching and formative assessment.

How did you set it up?

It is usually difficult on modules to extend an activity over several weeks, but we had a good opportunity on this module to do this because it was designed with an over-arching narrative structured into three components: Understanding problem, developing an intervention, and evaluating that intervention.

Although the summative poster submission is individual, we decided to use group work for the formative assessment activities so that students’ learning was scaffolded over several weeks through working with the same students in their group. In doing so, each student had a stake in the success of the group work, regularly receiving peer feedback on their understanding, as well as how they contributed to the group dynamic and project tasks. Each group was required to present their work on three occasions and receive feedback from the other students in the cohort. As the whole cohort was broadly focusing on the same topic, the peer feedback inherently functioned as self-feedback on their own group’s model and intervention.

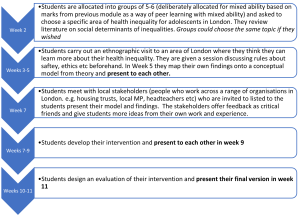

Timeline of the activities 10 weeks of the 12 week module:

- Padlet is used throughout for students to post their models and receive peer feedback and from the tutor.

- The poster is submitted before Week 12 with a 1000 word commentary/critique of the process of developing their intervention and evaluation of it.

How do you give feedback?

Feedback is crucial to good formative assessment (Boud and Carless, 2018) and we were keen to provide a range of opportunities for various sources of feedback:

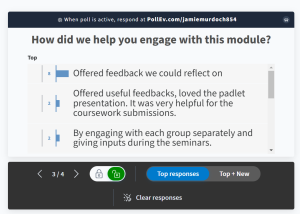

– from the tutor: this occurs throughout the module in the form of the Padlet for written comments and suggestions; in the small group discussion with probing and continuous feedback; and verbally at the end of each of the presentation opportunities.

– from the stakeholders: students have a chance to discuss their findings with our external partners and receive feedback and further ideas to develop their work.

– peer feedback– students are working in their groups to discuss and share ideas and have the opportunity to give and receive feedback in the presentation activities. They can also post comments and suggestions (anonymously if they feel more comfortable) using the Padlet.

– self-reflection: the 1000 word reflective commentary allows students to use all the feedback and consider their own individual process.

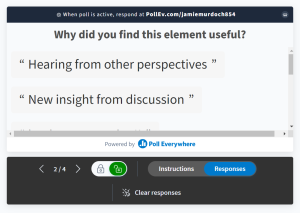

This type of 360 feedback is not only pedagogically desirable but also authentic in that this simulates how feedback is sought and received in the world of work. Students’ feedback to us as module leaders were that these feedback elements were particularly appreciated:

What benefits did you see?

- Inclusivity: students were developing communication skills and building their confidence as the module progressed as they were becoming visibly more comfortable sharing ideas. Because they had 3 opportunities for presentations and were developing those skills in a formative context, there was less pressure for them in oral assessment.

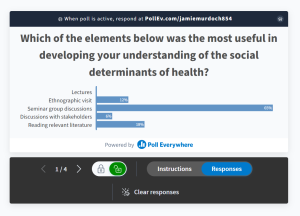

- Engagement and intellectual skills: adding the formative activities, in particular the ethnographic fieldwork gave them experience with hands-on practical application of theory and enabled them to make a link between abstract concepts and the reality of London life.

We were initially concerned that by working together throughout the seminars in this way, the students would get fed up doing this project! But we found they were actually more motivated to do the work for the summative assessment, perhaps because they knew they had to come to class prepared to work on the assessment, and the activities were designed to be engaging and experiential. This is clear from student feedback:

Attendance never dropped below about 80% (22 out of a cohort of 31).

- Improved understanding of learning outcomes and assessment: in contrast to the previous year, we have had no student comments or concerns about how they have understood the learning outcomes and assessment. Next year, we will be able to evaluate the impact of these changes, specifically whether redesigning seminar activities has made a difference to student performance on the assessment.

- Teacher benefits: I personally found this way of working more interesting as I interacted more with students, which is the best part of teaching, for me!

What challenges did you encounter and how did you address them?

- How do you support students to pick out an area of London for their ethnographic visit? We set aside time in the seminar to discuss and think about what areas would be useful to investigate their health issue. We discussed dialogically how we would behave ethnographically and they come up with a ‘safe’ plan for gathering data.

- How did this work if people with no knowledge of London? No one explicitly raised this as an issue partly due to mixed groups where someone would have some knowledge. Also, students were already reading papers on London as this was part of module content, so they had some ideas already. It may be something to think about in future iterations with largely international cohorts.

- How did you manage the group work?

A). The groups were small (5-6 people) and the longevity of working together over the module duration meant that they got to know each other and were more confident in sharing ideas.

B). Crucially, each week, time was set up within the seminar to work on the project, where seminar leaders could sit in on the group discussions to offer constructive support.

C). We sometimes mixed up the groups e.g. using a jigsaw activity where they worked in one group to report findings from a particular paper and then returned to their groups to report back. This allowed them to work with other people and prevent silo-ed thinking.

There was one group with a dominant student and some people were still quiet. Students often resolved these issues themselves, but it was easy for us to step in during the seminar because a lot of the work was being done in class. One student was anxious socially and struggled in group work but we were very careful not to force anyone to speak as people often participate in different ways in groups.

- How did you manage the relationship with stakeholders?

This is crucial and we were lucky in our department that these relationships were already established. The MA in Public Health has a Stakeholder Engagement Group to draw on. When academic work with external partners and stakeholders, it must be a genuine partnership. Co-production with the community can be fraught, especially when talking about inequalities, and the relationship cannot only be seen as using them to help students with their research!

More practically, because we asked international speakers to come, we had to run this session online, which, although more convenient for speakers and allows us to source a more diverse group (for example we had a speaker form Kenya and one from Jamaica), it can be potentially less engaging for the students. We also had to ensure that each group had some time to talk with each stakeholder, and so setting up and managing the breakout groups was a key challenge! We had to be on hand to help our stakeholders when technological issues arose.

What are your next steps?

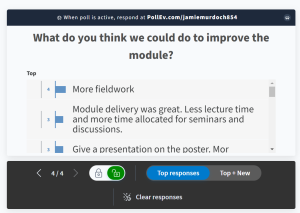

We asked students for what we could do differently, and they gave us three very good ideas which we will take forward next year:

We would like to give students an opportunity to present their poster, as the presentations they gave were formative and there was no corresponding summative presentation. Although we felt this increased students’ verbal communication skills in a low stakes environment, some students wanted to be able to demonstrate their acquisition of these skills. This could be added as a summative weighting or kept formative but in a conference style scenario at the end of the module.

Some students also asked for an example of a well-designed poster. Next year we would like to offer them some examples for them to analyse and see what makes a stronger and weaker poster, in particular how they used evidence to support their model and design of their intervention. There were some excellent submissions (see above) but we found that some students were still making some unsupported claims, so we would like to add an activity that focuses on this.

What advice would you give to colleagues who are thinking of trying this type of assessment?

Formative assessment should consist of different activities that enable students to interact with you and one another. When designing an activity, consider how do you change the quality of an interaction? The activity itself is less important than its core purpose/aim so don’t be afraid to try out a variety of new things! Not everything will work for everyone but experiment and evaluate.

Leave a Reply