by Neil Vickers, Reader in English Literature & Medical Humanities

Michael Balint is mentioned in medical humanities circles as a revered ancestor, much as one might talk about William Empson as a significant figure in the history of English literary criticism. Everyone knows they’re important but surprisingly few people read either writer today or even know why they should. (An important exception is Josie Billington’s superb Is Literature Healthy? – reviewed here – which devotes a chapter to Balint.)

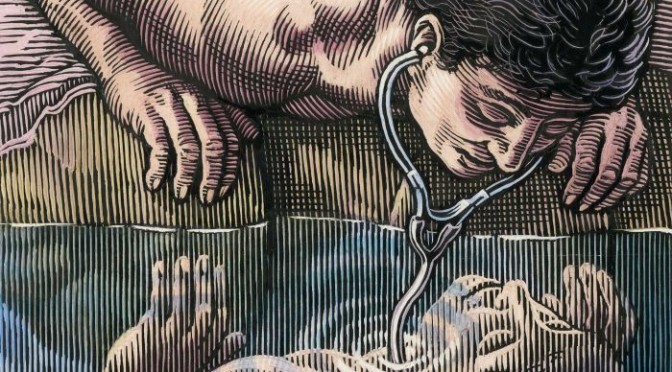

Empson did theory before Theory, and Balint did narrative medicine before Narrative Medicine. Both men were at least as interesting as what came after them, and yet both have become unduly sepia-tinted with the passage of time. Part of the reason for this fading in Balint’s case has to do with the fact that his clinical examples are firmly rooted in the sociological reality of the 1940s and 50s. The world Balint describes is hidebound by class. As a psychoanalytically-minded medical humanist, I occasionally press a copy of Balint’s classic, The Doctor, the Patient and the Illness (1957) on MSc students, but always with the caveat about his antiquated case material. ‘Someone should update it,’ I whisper, as they saunter out of the room.