William Burgess and Felicity H-Mackie of the MA 18th Century Studies course organised a conference in conjunction with the Centre for Enlightenment Studies, as an opportunity for 18th Century MA researchers from King’s and Queen Mary to discuss the first stages of their dissertations with students and staff. They share with us here their dissertation research journeys.

by William Burgess, MA 18th Century Studies

Like all good research journeys, my dissertation started with the discovery of a quotation that upended everything I thought I knew about literature.

Following my BA graduation, I spent the summer reading Samuel Johnson’s 1759 novel Rasselas. Aside from getting a lot of stick from my friends (most of whom were taking it easy with some crime fiction or re-reading Harry Potter) reading the novel revealed some unsettling complications to my idea of what literature means.

“If we speak with rigorous exactness, no human mind is in its right state. There is no man whose imagination does not sometimes predominate over his reason, who can regulate his attention wholly by his will […] all power of fancy over reason is a degree of insanity.”

Samuel Johnson is telling us that everyone, to some degree, is a bit ‘insane’. Not only that, but – as he goes on to insist – the act of writing fiction is by definition slightly mad.

Maybe I’m just making excuses for my previous naivety here, but I think the pedagogy of English Literature encourages you to read deliberateness and intent into every syllable of the written word. Close-reading, syntactic analysis, and looking for internal evidence of intertext was certainly not discouraged, and during my undergraduate study I found myself buying into the Enlightenment myth that everyone wholly means what they say.

Rasselas shook this conceit of mine to the core, and aside from its inconvenient timing (where were you before my finals, Johnson?) it has affected the way I’ve approached literature ever since. How could one of the leading intellectuals in an ostensible age of reason say that every writer was mad? If no one’s ‘mind is in its right state’, whose writing can we trust?

These were, and have remained, the originating questions of my dissertation project. I think they’ve endured for me partly because they behave very differently when you apply them to different genres of writing.

In court cases, for example, the conversation is very explicitly all about answering these questions. But what happens when the plaintiff decides to publish an account, and that account is the only record that survives? Can we take their word for it, or can we read the defendant’s voice between the lines? What about medical case histories? The physician is a trained professional, of course, but what assumptions are they making about a patient’s body or mind? Is the patient being honest in their interview?

As you can see, Johnson provokes more questions than answers. Nevertheless, as my dissertation stands now, these questions all seem to be organising themselves around the idea of self-authorisation, of personal subjective truth versus a conception of common sense, and I think this is where the project will be heading.

One aspect – maybe even a governing principle – that I’ve not mentioned yet is Cervantes’ Don Quixote, whose hero has been watching venerably over my whole project. The novel is all about these same ideas of what madness is, self-authorisation, subjective truth and empirical inadequacy. The more you look, these themes abound in eighteenth century literature.

At the moment, I’m hoping to bring together a number of different genres – specifically those court cases and case histories related to madness – and navigate them using the near-ubiquitous themes of eighteenth-century quixotism. So far, it seems to be shedding a lot of helpful light on an area at the centre of how the period regarded, authored and questioned itself – but, as Johnson tells us, nothing is really what it seems.

by Felicity H-Mackie, MA 18 Century Studies

Re-writing someone else’s words in your own handwriting changes them a little. Plotting those words out and stitching them onto a piece of fabric does other funny things.

I once reinterpreted some lines from Annabella Blount’s ‘A Cure for Poetry’ (c. 1741), for an alternative assessment.

‘Where poets stood before receipt-books stand,

Silk, thread and worsted are my next demand,

And chairs and stools increase beneath my labouring hand.’

(Anabella Blount, ‘A Cure for Poetry’, Eighteenth Century Women Poets: An Oxford Anthology, ed. Roger Lonsdale)

I embroidered these lines in backstitch and decorated the border of the fabric with traditional cross-stitched motifs taken from eighteenth-century needlework samplers. While it was very basic work and has since been put into storage (so no photos unfortunately!) it was challenging, and forced me to approach my ideas about texts and literary creativity from a completely new perspective. In addition to playing with the relationship between form and content, I gained a better understanding of the skill involved in fine needlework and found that it requires serious investments of time, physical effort and mental energy.

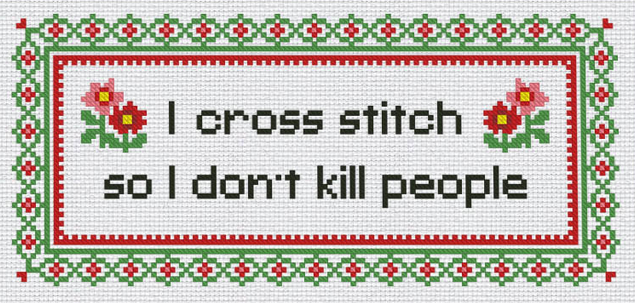

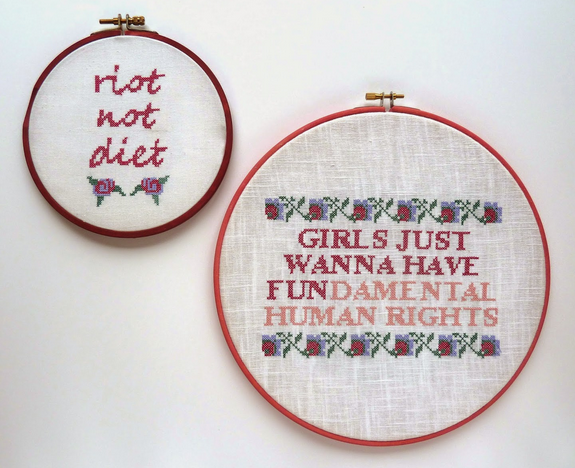

Texts and textiles both tell stories, and needlework in particular (compared with dress-making or knitting for example) has a clear affinity with words and language. Embroidered poetry and biblical quotations frequently appear in eighteenth-century samplers and the device has evolved into the trend for ironic cross-stitched phrases which appear on Pinterest and Etsy today. Modern textile art tells complex stories and takes highly various forms, from personal arts and crafts work, to large-scale Craftivism (see the guerrilla knitting movement Knit the City).

Something about the physical engagement and accessibility of textile work is clearly attractive, and the subversive humour of sassy cross-stitch patterns has encouraged more people to sew purely for decorative purposes.

These patterns subvert the values signified by the traditional needlework sampler, so renowned for teaching girls proper feminine behaviour and accomplishment. They reclaim a skill and push against a narrative which designates embroidery as an activity which historically oppressed women’s bodies and minds.

But is the characterisation of eighteenth century fine embroidery as an oppressive activity entirely accurate or universal? Who exactly produced needlwork, and when and why did it come to be so closely associated with exemplary feminine behaviour? When the material and the literary are combined, the creative and conceptual potential of both mediums are enhanced. Any readings of these text-textiles hold implications for both the history of the book and the study of women’s histories.

After completing that first poetry-embroidery project, I began to pay attention to literary words in material forms and the meanings which could be read in these material-textual relationships. My ideas about texts and where they could be found changed, and I formed ideas which I feel can contribute to, and perhaps complicate, the critical conversation about the recovery and rediscovery of women’s writing and art. In my final dissertation, I’m using these thoughts as a starting point for discussing issues concerning authority and material form, with regard to women’s authorship and creative production in the eighteenth century.

You may also like to read

The Political Day in Georgian London

Long Read: Arabic Illness Narratives and National Politics

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.