Next up in our myth-busting series, Yasmin [EDIT lab PhD student] and Elisavet [EDIT lab placement student] address the common misconception that you either have a mental health disorder or you don’t. The truth is, it’s not that simple.

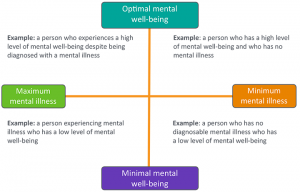

We all have mental health, be it good or average or not so good. It “includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being and affects how we think, feel, and act”. Just as with physical health, everyone’s mental health can fluctuate. Some people experience one-off episodes of bad mental health, when they might exceed the ‘cut off’ for a diagnosis of a mental health disorder. Some people go on to have repeated episodes of mental ill-health that they will have to live with for the rest of their life. But these individuals can also have periods when they experience high levels of mental well-being. So really, it’s quite hard to define someone as definitively mentally healthy.

Symptoms of mental health disorders are common within the population. For example, everyone has experienced the symptoms of anxiety (e.g. nervousness, increased heart rate or stomach tensing), depression (e.g. low mood, hopelessness or low self-esteem), and psychosis (e.g. paranoid thoughts – such as worrying that everyone is laughing at you when you walk into a room). These symptoms are our body’s natural responses to unfamiliar or stressful situations (e.g. see a previous blog post on the evolution of fear). But it is when these symptoms occur more often than usual, last for prolonged periods of time, become severe, and finally disrupt people’s everyday lives that individuals receive a diagnosis of a disorder, such as Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), for which they seek treatment (e.g. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)).

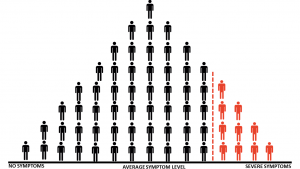

Take a look at the image below:

If we measured everyone’s mental health in the population today, we would find that most people would score somewhere in the middle of the spectrum with “average symptom level” (this is called a ‘normal distribution’). Fewer people would sit at the extreme ends of the distribution with “severe symptoms” or “no symptoms”. Individuals who score further towards the “severe” end would be more likely to receive a diagnosis of a mental health disorder (i.e. those people in red). But where we draw the red ‘cut-off’ line for a clinical diagnosis is somewhat arbitrary and debatable.

“It is when these symptoms occur more often than usual, last for prolonged periods of time, become severe, and finally disrupt people’s everyday lives that individuals receive a diagnosis of a disorder”

Health care professionals assess the severity of patient symptoms to inform their decisions in making a diagnosis. To help with this process they use diagnostic statistical manuals, self report inventories and other classification systems that outline specific criteria for disorders. These can include the use of standardised questionnaires to derive a ‘score’ for the patient’s symptom severity. For example, using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, a score of 10 points or more is usually taken as the cut-off point for a moderate to severe anxiety disorder.

However, your ‘score’, or severity of symptoms, is not fixed. Although you might exceed the clinical cut-off for a mental health disorder at one point in your life (1 in 4 people in the UK will fall within the ‘red section’ of the distribution in a given year), this is likely to change over time. Once a disorder is diagnosed, there are a variety of treatments available that can help to reduce the severity of an individuals’ symptoms. With the help of such treatments, individuals may go into remission and eventually no longer require a diagnosis. Equally, with successful treatment and adequate support, individuals who experience long term mental illness may retain their diagnosis for a while longer but have periods of high mental well being, when their symptoms remain low.

As with physical problems, some people may be more vulnerable or more resilient than others to experiencing a mental health disorder, due to a range of genetic and/or environmental factors (see our previous post on gene-environment correlation for further discussion on how genetic and environmental risk factors can be associated). Furthermore, individuals will only receive a diagnosis for a mental health disorder if they have access to professional services, which is not always the case.

“Diagnoses are not fixed and individuals with long-term conditions may not always show signs of mental illness.”

In summary, it is important for us to understand that we all have mental health and will all experience symptoms of mental health disorders at various points throughout our lives. However, individuals receive a diagnosis for a mental health disorder when these symptoms become frequent and debilitating. Diagnoses are not fixed and individuals with long-term conditions may not always show signs of mental illness. With the correct treatment and support, some individuals may experience optimal mental well-being, despite previously receiving a diagnosis of a mental health disorder.