In recent years, mindfulness has become increasingly popular and is being recommended as a preventative tool and a useful technique to deal with stress and anxiety. What exactly is mindfulness, how does it work and are there any associated risks?

What is mindfulness?

Mindfulness is a technique with Buddhist origins which develops self-awareness by focusing on your body and actions at the present moment. This process of becoming aware of your mind and body is done without judgement and can be used to improve your mental well-being as you develop an increased understanding of your thoughts and feelings.

For more information about self-care and using mindfulness, check out Molly’s post. And for more details, here is an interesting TEDx talk by Prof. Shauna Shapiro.

“mindfulness works by training individuals to shift their perspective from their own thoughts and learning to attend to their moment to moment experiences without judgement”

How does it work?

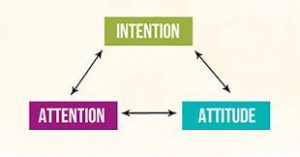

Prof. Shapiro explains that mindfulness works by training individuals to shift their perspective from their own thoughts and learning to attend to their moment to moment experiences without judgement, through a process called ‘reperceiving’ (Shapiro, Carlson, Astin & Freedman, 2006). Shapiro et al (2006) broke down the mindfulness process into three main components: intention, attention and attitude.

Intention

Shapiro found that when mindfulness is practised, an individual’s intentions change from regulating themselves, to exploring themselves and then finally to seeking liberation. Why someone wants to practice mindfulness is a key part of what they will achieve from doing so.

Attention

Attention is a principal component of mindfulness as individuals practice attending to their internal and external self by being aware of their moment to moment movements.

Attitude

In order to effectively practice mindfulness, students must approach it with a positive attitude full of curiosity, openness and patience to allow for non-judgemental growth and awareness.

Is it successful?

Interventions such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and Jon Kabat Zin’s Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) programme have been developed from mindfulness practice to treat common mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety. MBSR utilises yoga and meditation to treat sustained periods of stress, whilst MBCT is a low intensity group treatment usually used to treat depression (Kingston, Dooley, Bates, Lawlor & Malone, 2007).

There is some evidence to show that mindfulness interventions can reduce the chance of depressive relapse in individuals with a depressive disorder (Fjorback et al., 2011), however despite the growing popularity of MBCT and MBSR, there is little evidence to support the notion that a mindfulness approach alone can treat common psychiatric disorders (Hedman-Lagerlöf, Hedman-Lagerlöf & Öst, 2018). The majority of the research in this area suggests that mindfulness is most effective as a preventative practice, helping people to cope with stress that they may face from time to time (Poulin, Mackenzie, Soloway & Karayolas, 2008).

“mindfulness is most effective as a preventative practice, helping people to cope with stress”

Does it impact our brains?

Researchers in the field of mindfulness explain that long term practice of mindfulness can impact brain structure. More specifically, the anterior cingulate cortex (associated with attention) changes its structure with increased practice. In addition, changes have been seen in grey matter, brain stem, cerebral cortex and cerebellum which suggests that mindfulness meditation impacts a wide range of brain structures (Tang, Hölzel & Posner, 2015).

Are there any risks?

Despite positive results from research supporting the use of mindfulness, there have been some case studies detailing participants who have experienced adverse effects from mindfulness practice. In multiple cases, mindfulness interventions have triggered psychiatric episodes in individuals with a history of psychiatric illness. In some very rare cases, mindfulness has also been associated with dependence on meditation which can cause individuals to become antisocial, introverted and adopt a defeatist perspective on life (Shonin, Van Gordon & Griffiths, 2014). The greater concern however, is that individuals who are suffering from a psychiatric disorder may rely on mindfulness alone to deal with their disorder, preventing them from seeking treatment through a clinician (Hedman-Lagerlöf, Hedman-Lagerlöf & Öst, 2018).

With these potential drawbacks to mindfulness, it is important that individuals practice mindfulness in a safe environment whilst taking care to take precautions to limit negative effects. For a list of things to bear in my mind when practising mindfulness, visit https://www.mindful.org/is-mindfulness-safe/. If you feel you need help and want to understand more about different available treatments, visit your GP.

A few useful apps:

Insight timer – A free easy to use app with lots of different talks and guided meditations where you can filter meditations by theme, duration and difficulty.

Smiling mind – A free app which explains mindfulness and supports mental health, it is particularly good for young people.

Headspace – Full access to content requires a monthly subscription but students can bundle Headspace with their Spotify subscriptions for no additional cost. It is probably the most sophisticated app, with lots of different meditations to choose from and handy tips.

Evans, S., Ferrando, S., Findler, M., Stowell, C., Smart, C., & Haglin, D. (2008). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal Of Anxiety Disorders, 22(4), 716-721. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.005

Fjorback, L., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P. and Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy – a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), pp.102-119.

Hedman-Lagerlöf, M., Hedman-Lagerlöf, E., & Öst, L. (2018). The empirical support for mindfulness-based interventions for common psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718000259

Kingston, T., Dooley, B., Bates, A., Lawlor, E., & Malone, K. (2007). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychology And Psychotherapy: Theory, Research And Practice, 80(2), 193-203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/147608306×116016

Lau, N., & Hue, M. (2011). Preliminary outcomes of a mindfulness-based programme for Hong Kong adolescents in schools: well-being, stress and depressive symptoms. International Journal Of Children’s Spirituality, 16(4), 315-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1364436x.2011.639747

Poulin, P., Mackenzie, C., Soloway, G., & Karayolas, E. (2008). Mindfulness training as an evidenced-based approach to reducing stress and promoting well-being among human services professionals. International Journal Of Health Promotion And Education, 46(2), 72-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2008.10708132

Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Astin, J., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373-386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20237

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., & Griffiths, M. (2014). Are there risks associated with using mindfulness in the treatment of psychopathology?. Clinical Practice, 11(4), 389-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.2217/cpr.14.23

Tang, Y., Hölzel, B., & Posner, M. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916