As an avid film lover with a paired weakness for the attractive buzz and glamour of the red carpet award shows, I felt completely swept up in the excitement of the film awards season. It was therefore only natural for my friends and I to find ourselves huddled around my laptop screen in the small hours of a Monday morning, to watch the most reputable awards show of them all; The Oscars.

As many know by now, the 2017 Academy Awards was a dramatic and emotional night, most notably for being host to the biggest mistake in Oscar history. As the achingly uncomfortable moment unfolded in front of my eyes, I realized that I was squirming in my seat, my stomach dropping, and the instinct to recoil and turn away from the scene too overpowering for me to overcome. I was mortified for all parties involved, from the directors who believed that they had won the most coveted award of the night, to the nervous laughter from the presenters struggling to keep up the illusion that the night would still end on a graceful note. All I could think about was how horrible this must all be for them, yet my reaction would make you believe I was the one giving away my very own gold statuette. After my second-hand embarrassment had prevented me from enjoying the program I had stayed up until 2am to watch, I felt it was time to find out why that may be.

As many know by now, the 2017 Academy Awards was a dramatic and emotional night, most notably for being host to the biggest mistake in Oscar history. As the achingly uncomfortable moment unfolded in front of my eyes, I realized that I was squirming in my seat, my stomach dropping, and the instinct to recoil and turn away from the scene too overpowering for me to overcome. I was mortified for all parties involved, from the directors who believed that they had won the most coveted award of the night, to the nervous laughter from the presenters struggling to keep up the illusion that the night would still end on a graceful note. All I could think about was how horrible this must all be for them, yet my reaction would make you believe I was the one giving away my very own gold statuette. After my second-hand embarrassment had prevented me from enjoying the program I had stayed up until 2am to watch, I felt it was time to find out why that may be.

Second-hand embarrassment is essentially rooted in our ability to empathize, an important trait that allows us to understand what others are feeling. As social animals with an inclination to feel part of a community and continue to live harmoniously within that community, empathy is crucial. According to Baston et al. (1981) an altruistic mind-set promotes concern of others’ well-being and therefore motivates helping behaviour. This helping behaviour in turn encourages the well-being of the entire group.

“All I could think about was how horrible this must all be for them, yet my reaction would make you believe I was the one giving away my very own gold statuette.”

So, if empathy is such a positive trait, beneficial to our social relationships, why does it sometimes take the form of an overwhelming feeling of dread?

Further research suggests that despite the existence of altruism, humans are not as selfless as they may seem. May (2011) argues that the only way in which individuals could feel motivated enough to engage in helping behaviour would be if they felt it would ultimately benefit them as well. For example, you may describe your empathy for someone who has been placed in an unfortunate situation as a feeling of pity. The reason that you then seek to help out this individual is because you know that you will feel the negative emotions of shame or guilt if you do not. Your seemingly thoughtful act of altruism is therefore a masked act of egotism, marked by your pursuit of guilt release. Ultimately, the process is a little like your brain holding your emotions hostage until you take action to help those around you.

In order to determine the neural pathways involved in second-hand embarrassment, a group of German and British psychologists undertook a study observing the mental processes that occur when people are faced with unseemly uncomfortable situations. They provided their participants with different stimuli, including sketches depicting embarrassing scenarios involving a protagonist, as well as written vignettes of an embarrassing situation. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), this group concluded that the anterior cingulate cortex and the left anterior insula are strongly implicated in experiences of ‘social pain’ related to the misfortune of others. These are the same cortical structures that were found to be involved in the mental responses experienced when witnessing another person’s physical pain.

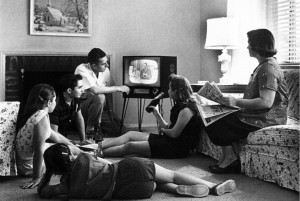

Watching TV frequently results in feelings of empathy with no outlet – as you are unable to help those on the screen.

Watching the Oscars was a great example of empathy with no outlet, resulting in an overdrive of vicarious embarrassment. As I watched all parties involved struggle to understand how to proceed in front of a live audience of 3,000 people and a much larger audience of viewers across the globe, I pitied everyone on the screen yet was handicapped by my inability (and frankly, everyone’s inability) to resolve the issue for them. My sweaty palms, twisted stomach and burning cheeks were therefore empathy pains that I could not soothe, resulting in my defeat and my decision to stop watching.

“Although empathy is an innate personality factor, variation in this trait can result in different degrees of reaction to embarrassing scenarios.”

Interestingly enough, while I struggled with my own emotions throughout this nightmare of a scene, my friends seemed to have a polarized reaction. They instead were glued to the screen, shocked into laughter and fumbling with their phones to record the entire debacle. Although empathy is an innate personality factor, variation in this trait can result in different degrees of reaction to embarrassing scenarios. Furthermore, as high levels of trait anxiety correlate with conscientiousness, the main trait associated with empathy, these results suggest implications for further studies on the prevalence of so-called ‘second-hand embarrassment’ in clinical populations.

[…] and uninhibited portrayals of male emotionality and mental illness (on another note, see Sarah‘s post for her take on on the moment when Moonlight won best picture). Around the same time, […]