By Ali Glossop, On Purpose Associate in the Widening Participation Team|

Where you live is a contributing factor to how likely you will be to go to university.[i] Higher education participation rates vary across the UK, for example young people with fewer opportunities in remote rural and coastal areas are half as likely to enter university compared to those living in major cities.[ii] The distance between home and university is strongly linked to where you choose to go, too. According to the Social Mobility Commission, “In most of the ten worst-performing local authority areas for youth social mobility, many parts of the locality are about an hour each way from the nearest university by public transport – and often even further from a selective university.”[iii]

King’s College London is committed to increasing social mobility and widening participation, and we want to find the brightest young people regardless of background – or postcode. To help widen opportunity for those in low participation areas, we’re developing our outreach work further outside of London, for example through the Hastings project with Eggtooth and expanding K+ into Essex. Coastal Kent has been identified as the next region of focus and the aim is to develop a programme addressing barriers specific to those living in the area, around applying for and going to research-intensive and Russell Group universities.

First impressions

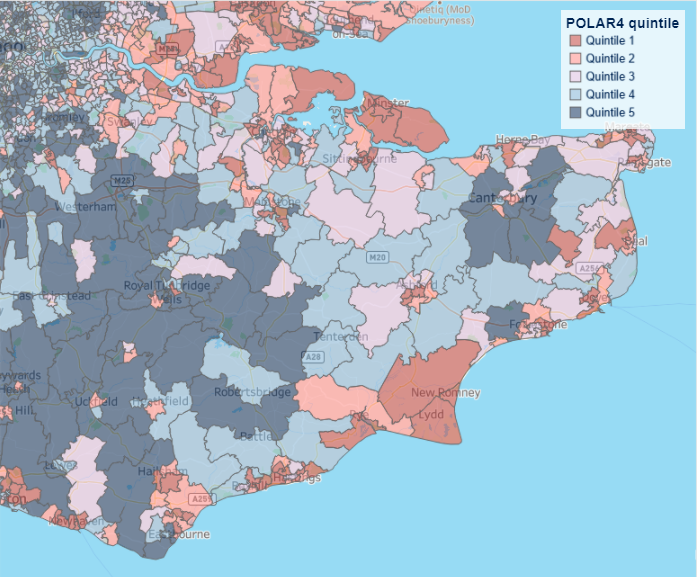

Looking at participation rate data (POLAR4), it was really interesting to see how much variation there is within Kent. Areas around Canterbury, Tunbridge Wells and Sevenoaks have high participation rates, but there is a swathe of areas along the coast around Medway, Swale, Thanet, Dover and Shepway that have low participation rates.

Figure 1 POLAR4 map of Kent from Office for Students, showing variation within the region.

Source: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/young-participation-by-area/map-of-young-participation/

Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) data showed a broadly similar picture, as shown in the figure below. Isle of Grain, Isle of Sheppey, Rochester, Chatham, Sittingbourne and Faversham were starting to stand out at the north of the region; Margate, Broadstairs and Deal in the east; and Folkestone, Dover, Lydd and New Romney in the south.

Figure 2 Overall IMD2019 national rank of Lower Super Output Areas in Kent and Medway. Source: The English Indices of Deprivation 2019: The Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. Map produced by Kent County Council.

© Crown copyright and database right 2019, Ordnance Survey 100019238. https://www.kent.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/7953/Indices-of-Deprivation-headline-findings.pdf

Narrowing down

We wanted to identify two areas within Kent to carry out research and develop a pilot programme. For each area, we used data extracted from HEAT and worked out the number of POLAR4 Quintile 1 and 2 Middle Layer Super Output Areas (MSOAs – a statistical unit used to report small area statistics). Then for each MSOA, we looked at the average participation rate and estimated young population of POLAR4 Quintile 1 and 2 students – and the same for TUNDRA. We also studied the level of deprivation in each of these areas, by looking at IMD data (from the University of Sheffield). We then ranked the areas against each of the data points. Swale, Thanet and Medway came out as the top three. We decided to focus on Swale and Medway since these areas are more accessible to London – we knew that some element of the programme would involve travelling to King’s campuses or staff travelling to schools.

Kent grammar schools

One element that we wanted to consider during our research was the Kent selective system because this seemed to be a defining characteristic of the region. Kent has 38 grammar schools, which makes it the county with the highest number of grammar schools in the UK. Medway has 10 non-selective state 11-18 schools and 6 selective schools. Swale has 5 non-selective schools and 3 selective schools.[iv]

We looked at HEAT data and saw that grammar schools had higher POLAR 4 participation rates than non-selective schools by 16% in Kent. It is perhaps unsurprising that the participation rate for young people at selective schools is higher than for those at non-selective schools; in this sense the grammar schools act as a vehicle for social mobility. But we were curious to know to what extent the Kent selective system is a barrier to studying at research-intensive universities for those that don’t pass the 11+ exam, and what impact, if any, this has, in order to start thinking about how we could work with non-selective state school students in Medway and Swale.

Listening to people in Kent to help us plan our project

At the outset of the project it was clear that part of our research would include a ‘listening campaign’ based on Citizens UK community organising and social research techniques. King’s has a partnership with Citizens UK and uses relational approaches within several projects.

We spoke to universities in Kent as well as WP organisations and charities, which provided us with helpful and important context and background information. With support from the What Works team, we then conducted qualitative research. We interviewed eight teachers, three parents and three students (half the sample we planned, but COVID-19 restrictions made research difficult) – from both selective and non-selective schools. In coding and analysing our transcripts, what struck me was the impact on confidence and aspiration that not passing the 11+ can sometimes have, and that students could almost be put on a different path by that one exam; resulting in little knowledge or appreciation of what university life might be like or the benefits it might afford them. These interviews gave us useful information to triangulate with other forms of research and gave us a start in thinking about what outreach practices may be helpful and what we may want to test empirically.

How will we know it has worked?

Using these findings, we created our Theory of Change, inviting along a parent from Kent, who was really useful in keeping us on track with our thinking and helped us bounce around ideas. Our Theory of Change is our plan for what we want to change, how we’re going to do it, and how we’ll know we succeeded. You can find out more here.

Our mission will now be to design a programme to help with these issues and to pilot it from November 2020. How will we know it has worked? If our programme sees an increase in applications to research-intensive universities like King’s from students at non-selective state schools in Medway and Swale, we’ll know we’re doing the right thing. There are also other things we can measure to give us indicators that we’re on the right track, like knowledge of the university landscape and reported self-efficacy. We don’t know much more than that yet, but what’s clear is that we know we need to start small and build a long-term programme, working closely with the non-selective school community in Medway and Swale before expanding and adjusting our outcomes measures accordingly. We also recognise the importance of continuing to listen and gain insight from the local community, adapting and reiterating the new programme as we go.

Personal reflections

It has been a brilliant and rewarding project to work on, learning about Medway and Swale, listening to people there and designing a new pilot programme. I’m really grateful to our interview participants who have given us their time and insights into their personal experiences, as well as universities in Kent and WP organisations and charities that provided us with such useful context. There have been a few challenges along the way – pre-COVID, I imagine I would have taken the train to talk to people and enhance my understanding of the area, but video calls have been a good substitute for that. My six-month On Purpose placement has gone incredibly fast and I can’t wait to see where the programme goes from here, hopefully towards increasing opportunities for young people in Medway and Swale to study at research-intensive universities like King’s!

_______________________________________________________________________

Read our reports

Click here to join our mailing list.

Follow us on Twitter: @KCLWhatWorks

[i] Home and away. Social, ethnic and spatial inequalities in student mobility. M. Donnelly & S. Gamsu (2018). Sutton Trust.

[ii] State of the Nation 2017: Social Mobility in Great Britain – Social Mobility commission.

[iii] State of the Nation 2017: Social Mobility in Great Britain – Social Mobility commission

[iv] Grammar school statistics: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01398/ (2019).

Leave a Reply