By the What Works Intern |

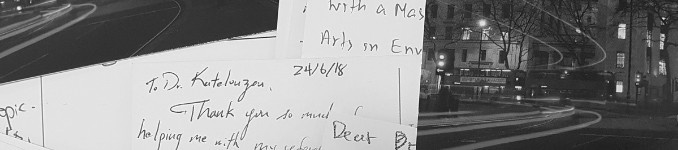

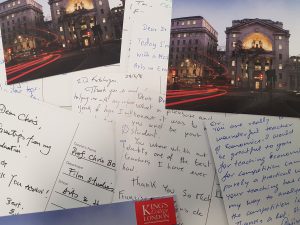

Recently the What Works Department, along with some help from our friends at BIT, started running an intervention offering graduands the opportunity to write postcards to former college and secondary school teachers. The intervention, SHIFT, is straightforward and you can read about it here.

Naturally, we expected some might want to write to people other than their former teachers: parents, friends, tutors, mentors. But we were blown away by the strength of feeling graduands have toward their former professors – there were some incredibly touching messages written to lecturers.

This is important for two reasons. Firstly, letting an intervention go off-piste can add unexpected value; we were hardly going to tell students, especially on graduation day, that they aren’t allowed to write to lecturers because it’s ‘not in the trial protocol’.

In fact, we are delighted to share these messages with lecturers and staff throughout King’s. Participants clearly enjoyed writing to a range of people they considered significant to their journey. Buoyed by the day’s celebrations, our stand received a steady flow of happy students (with a few tearful parents) throughout the graduations. Given research indicates showing gratitude is beneficial for both the giver and receiver, we’ve no doubt our presence at the stand was a value-add to students and postcard receivers alike.[i]

Secondly, running interventions means getting stakeholder buy-in – particularly in higher education. Convincing people to support, fund and engage with the interventions you run will depend, in part, on how your previous interventions played out. Until we reach the sunlit uplands of every senior stakeholder advocating the benefits of randomised control trials, that won’t change. By demonstrating the potential of the nudge in such an emotive way, we hope this intervention won over some hearts; it’ll be up to the data and analysis to win their minds.

When designing an intervention, we try to consider the risks and account for them in the planning stage. One component of this is accounting for how participants might want to change your intervention. Our key takeaway from this trial is that we need to think much more deliberately about how participants might engage with an intervention. We usually ask ourselves whether this is something people are likely to do – but we also need to ask ourselves, what are people likely to do with this?

With something as emotive and personal as SHIFT, we probably should have expected students to make their mark on the project. This was a happy alteration. In future, if you expect participants will alter the trial – consider the consequences of letting them do so. In this case, the downside was a decreased sample size, but the upside was considerable: happy graduates, happy parents, thrilled professors and more institutional awareness of what we can do.

There are times when keeping an intervention on the straight and narrow is necessary. If going outside the scope is going to mess with your data, cost a truckload of money or ruin your trial – don’t do it. Fortunately, this was not one of those times.

Click here to join our mailing list.

Follow us on Twitter: @KCLWhatWorks

______________________________________________________________________________________

[i] Kumar, A., and Epley, N. (2018). Undervaluing Gratitude: Expressers Misunderstand the Consequences of Showing Appreciation. Psychological Science, pp.1-13.

Leave a Reply