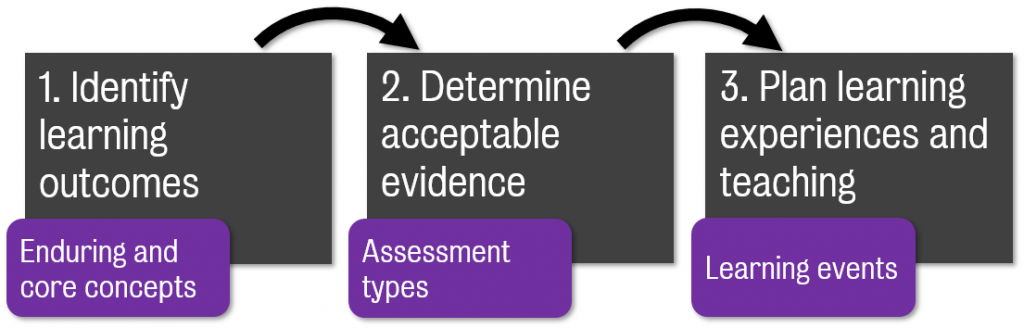

(After Wiggins and McTighe, 2005)

1. What are your goals and outcomes?

Before you start using ‘Active Learning at King’s’, we ask you to revisit your overarching goals for your students in society and then to unpack these goals into knowledge, skills and attitudes – your explicit learning outcomes for students. Here we take a backward approach to curriculum design informed by Fink (2003) and Wiggins and McTighe (2005).

- What do you intend students should know or be able to do after completing the activity, and how does this relate your your outcomes?

- What values or attitudes do you want to inculcate? How can you support students’ self-awareness about their academic practice?

- How would you like students to reflect on their learning and the curriculum?

- How can you equitably teach all the students in the room?

(Based on Angelo and Cross, 1993 and Tanner, 2013.)

2. How can students demonstrate they have met the outcomes?

After settling on outcomes, a backward design approach identifies the assessment tasks in which students demonstrate that they have met these outcomes. Refer to ‘Assessment for Learning at King’s‘ for guidance, including formative assessment which gives students opportunities to practice and master the outcomes.

We can think of active learning as a form of assessment for learning – an opportunity to check students’ progress and give feedback.

3. Use this guidance to help plan learning activities

‘Active Learning at King’s’ contains some tried-and-tested activity designs for you to use and adapt. Each describes a single activity and includes context, step-through guidance, considerations and examples.

Activity design happens after the outcomes and assessments have been settled. By this stage you have a clear idea of what students need to know, do or believe in your subject area, and how they will ultimately demonstrate this to assessors. Each activity you design will be an opportunity for you to check students’ progress – their practice and progressive mastery of the outcomes. With these purposes in mind, the following active learning continuums (based on Bonwell and Sutherland, 1996) will further inform your plans:

- The complexity of the activity, from straightforward to complicated.

- The level of interaction between students, from independent work to interdependent collaborative groups.

- Your students’ experience with the concepts, teaching approaches and each other, from inexperienced to experienced.

- The physical and digital learning environment, from fixed to flexible.

Once you have considered these questions, you are ready to design the activity.

4. Consider links

At this stage you have revisited your outcomes and planned one assessment or more. Through the ‘Guides’ menu you can access a collections of guides organised by the continuums above.

Individual activities need to be knitted into the curriculum to help students make connections between discrete facts and skills, and gain a holistic view of their module and programme. One possible approach, ABC Learning Design, is a 90 minute hands-on storyboarding workshop conceived at UCL (Young and Perovic, 2019) in which teaching teams sequence activities on a timeline and consider whether the types of learning (e.g. acquistion, production, discussion) represented on the storyboard will help students succeed in the course. Since the pandemic, institutions in several countries have explored running ABC online.

That is not to close off opportunities for contingent, responsive teaching though. As your confidence grows you will develop a repertoire of activities and a nose for when to use them. So in short, have an overall design set out and know when to depart from it, keeping your intended outcomes in mind.

5. How is it working?

To support your inquiries into how your activity designs are working in practice we introduce some evaluation approaches.

First times you try anything are usually messy, so if it doesn’t go entirely right don’t despair. Think about refinements you could make, then just do it again.

References

Angelo, T.A., Cross, K.P., 1993. Classroom assessment techniques: a handbook for college teachers, 2nd ed. ed, The Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco.

Bonwell, C.C., Sutherland, T.E., 1996. The active learning continuum: Choosing activities to engage students in the classroom. New Directions for Teaching and Learning 1996, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.37219966704

Fink, L., 2003. Creating significant learning experiences: an integrated approach to designing college courses, 1st ed. ed, Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, Calif.

Tanner, K.D., 2013. Structure Matters: Twenty-One Teaching Strategies to Promote Student Engagement and Cultivate Classroom Equity. CBE—Life Sciences Education 12, 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-06-0115

Young, C. and Perovic, N., 2019. ABC Learning Design. https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/abc-ld/

Wiggins, G.P., McTighe, J., 2005. Understanding by design. Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.