“We want our colleagues to embrace this new way of teaching, and we know that can’t happen if we place too much of a burden on them.”

There are several challenges, both pedagogic and motivational, in successfully implementing a PBL approach. The team behind the Engineering: Creating Technologies that Help People module in the summer school have had to keep these are the forefront of our thinking when designing the module.

The main pedagogic challenges are timetabling PBL modules, allocating teaching resources and deciding on assessment methods. Instructors unused to the approach often face a steep learning curve and, structurally, university departments may struggle to allocate sufficient staffing resources to the PBL stream, particularly in the early stages of adoption when the majority of instruction continues to be offered via the more-traditional large-scale lecture. Proper planning – and the allocation of sufficient resources to planning – in advance of the launch of a new PBL stream is essential, as is continued monitoring of the impact of PBL on instructor workload once the stream has launched. We want our colleagues to embrace this new way of teaching, and we know that can’t happen if we place too much of a burden on them.

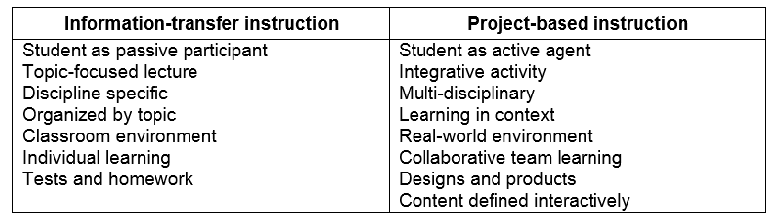

The main motivational challenge is getting students who arrive at university having only received information-transfer based instruction to actively engage with this new approach to learning. For example, a team from Dublin Institute of Technology examined the student experience of a PBL module offered as part of the 1st year of one of their undergraduate engineering courses.1 The module had two competitions, an intermediate competition at the midpoint and a second at the end; and the Dublin team found that students did not really commit to the PBL approach until the date of the first competition approached i.e. until the very last moment.

“When examining what reasons students give for feeling motivated by a project, one of the themes that comes up most often is “authenticity”.”

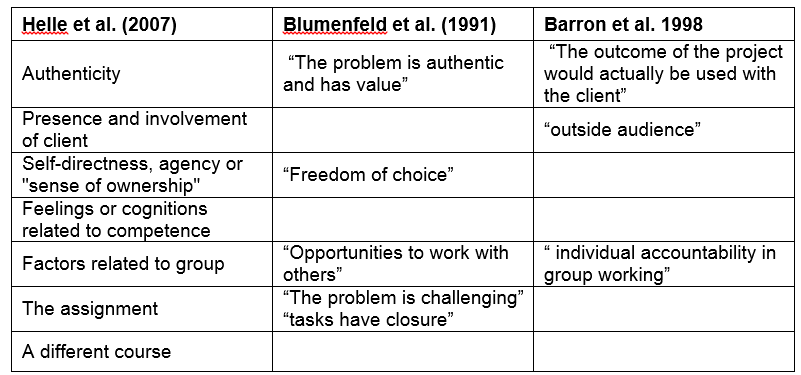

The Dublin PBL module was centred on creating a robot to take part in a Sumo wrestling contest (the second competition). However, when examining what reasons students give for feeling motivated by a project, one of the themes that comes up most often is “authenticity” – having a real-world problem to solve. The table below, taken from a Finnish study2 of two projects assigned to IT students, summarises the findings of three earlier studies that touched on motivational factors. Taking out the aspects centred on the team-based project aspects common to all PBL, we have factors related to the “real world” – authenticity, and, related to this, the existence and participation of a client.

At the same time, the Finnish study found that there two project teams sometimes felt pressured by having to meet the expectations of the client and tackle a real-world problem [that they may see as intractable]. It is here where support from the instructor/advisor is key providing context, encouragement and helping the students focus on achievable goals and maintaining a good working relationship with the client.

At the same time, the Finnish study found that there two project teams sometimes felt pressured by having to meet the expectations of the client and tackle a real-world problem [that they may see as intractable]. It is here where support from the instructor/advisor is key providing context, encouragement and helping the students focus on achievable goals and maintaining a good working relationship with the client.

“The role of the instructor/advisor is to support the student with encouragement and context”

So these are the factors we’ve had to think about in putting together our Engineering module. And with these in mind we’ve designed a learning experience centred on bringing together students and clients to solve real-world problems. Project-Based Learning is a powerful tool for helping deliver knowledgeable students who are active in pursuit of their own learning, but the choice of project is key to triggering engagement with an approach that the student will likely be entirely unfamiliar-with upon arrival; keeping it real delivers that engagement. At the same time, we recognise that the authenticity of the scenario can also prove daunting. So we’ve recruited a team of instructor/advisors ready to support the student with encouragement and context, giving them the confidence to make this leap from the classroom into the real world.

“We need to make sure that in keeping it real, we don’t also make it miserable.”

And there is one last thing we know we need to get right: we need to make sure that in keeping it real, we don’t also make it miserable. I think Beau Lotto, neuroscientist and expert on perception said it best: “Uncertainty is what makes play fun. Right? It’s adaptable to change. Right? It opens possibility, and it’s cooperative. It’s actually how we do our social bonding, and it’s intrinsically motivated. What that means is that we play to play. Play is its own reward.

“Now if you look at these five ways of being, these are the exact same ways of being you need in order to be a good scientist. If you add rules to play, you have a game. That’s actually what an experiment is.” Beau Lotto, TED Talk “Science is for Everyone, Kids Included” 06/12

References

- Duffy et al “Student Experiences of a Project-based Learning Module” 41st SEFI Conference 2013

- Hilvonen and Ovaska “Student Motivation in Project-Based Learning”, International Conference on Engaging Pedagogy, 2010