Kat is a research student in the Department of Culture, Media & Creative Industries at King’s College London.

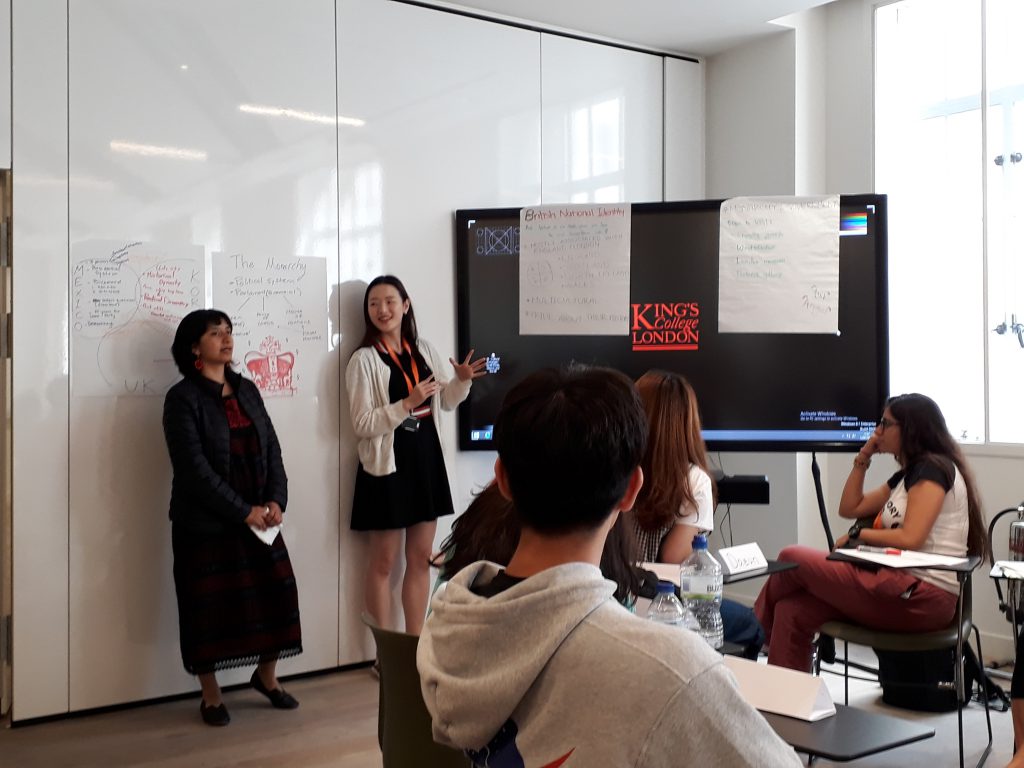

In 2019, when I taught the Media, Gender and Culture module for the first time, I thoroughly enjoyed the challenging yet rewarding time as a summer school tutor. Teaching the course again in 2020 and 2021, in the context of the pandemic, was inevitably a very different experience. Sessions needed to be redesigned to work effectively online, and there were practical barriers to address as well, from students’ Internet connections to the availability of teaching resources in different countries. However, through testing different approaches and carefully revising the course material, I was able to create an engaging online summer school experience for the students on the course. Below are my top five tips for course design and online teaching practice in the summer context:

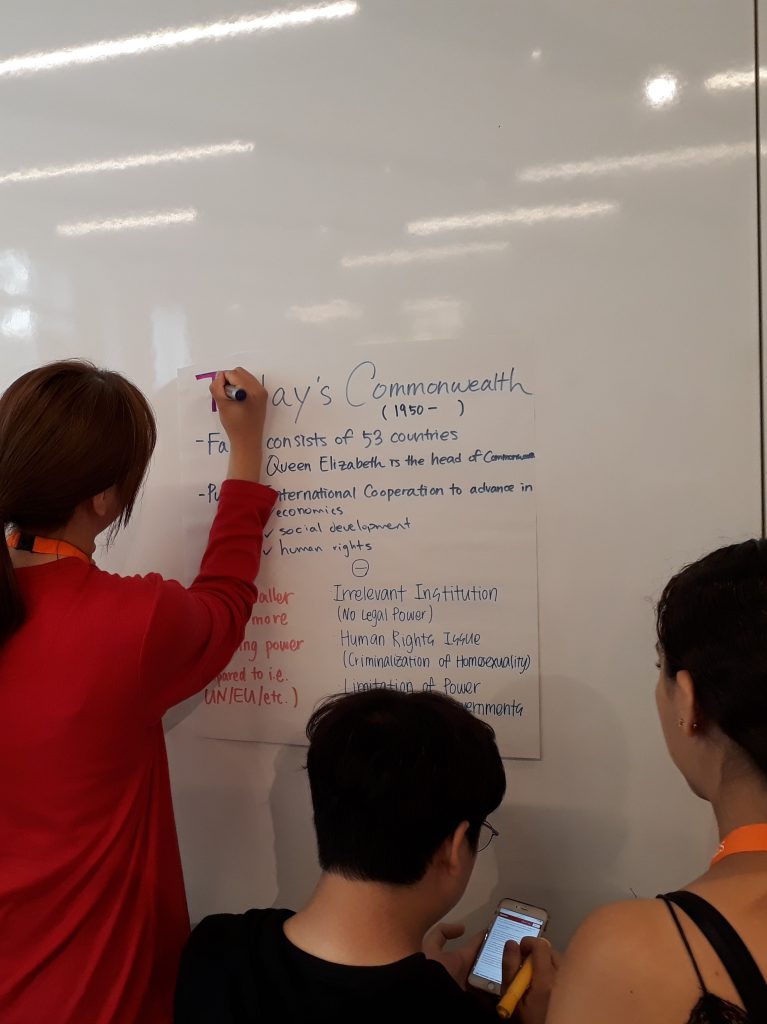

- Don’t try to replicate a face-to-face module in an online context. Online learning is an experience in itself and works best if approached as such. For instance, simply throwing in some discussion questions, as we may do in offline seminars, may not work in an online setting where engagement levels can vary (Zoom fatigue has become a term we are all too familiar with by now). Instead, I developed shorter, simpler tasks and activities that involved students actively doing something, such as watching a brief video clip and then conducting an analysis in groups.

- Find alternative channels for student participation and interaction. With the majority of summer school students being non-native speakers and in some cases having experienced educational systems in which speaking up in class is not always encouraged, a reticence to participate can be intensified in the online classroom – especially when students are unable to turn their cameras on due to connectivity problems. Thus, it was crucial to find other ways to enable student participation. One way was to invite my students to actively contribute via the chat. While this often meant that students wrote much shorter comments than they would when speaking out loud, I found that it benefitted especially those students who otherwise would not speak in class. Students organically started commenting and ‘liking’ their peers’ contributions, which helped foster a sense of community among a diverse group which had never met in person.

- Using emoji reactions, such as thumbs up or clapping hands, can be an extremely useful communication tool. Given the lack of non-verbal communication and body language, I regularly asked my students to “send me an emoji” to indicate their agreement to simple yes/no questions. For example, when working on a task individually, I would ask students to indicate via emoji if they needed more time to work on said task. Emojis can also be useful as an icebreaker activity, when inviting students to choose an emoji that expresses how they felt that day. Emojis were a shared form of communication which felt fresh, low stakes and spontaneous to students, and helped build a welcoming atmosphere in the class.

- Vary your platforms. Being in the same online meeting room every day, even if just for an hour, can be quite tiring. Therefore I incorporated activities on other platforms, such as Padlet, Mentimeter, or within Teams channels. The latter also meant that students would often continue discussions held during class after the live sessions had ended, including posting links to additional material. And again, these non-verbal activities were a great way for quieter students to still actively contribute to class!

- Be patient and flexible. There will always be unforeseen technical complications when running a course online, from students having microphone issues to breakout rooms not working as intended. As such, it is important not to overload a session with activities and to be prepared to improvise. The same is true for the asynchronous online learning that summer school students are asked to do in their own time. With most people reading everything on screen nowadays, it is important to choose short yet engaging readings (these do not always have to be academic, or could even be a website), but also include other activities, such as watching short video lectures, conducting independent research or brainstorming, or contributing to a Padlet.

Overall, my experiences showed me that King’s Undergraduate Summer School does not have to physically take place in London in order to be a unique experience. While the London location is undoubtedly an asset, there are many other contributing factors to the success of a module. As a colleague has elaborated on this blog before, we the tutors play a huge role in personifying the King’s experience. The above-mentioned steps, particularly the use of various channels of communication, as well as the general feeling of ‘we are all together in this online learning experience’, meant that I was still able to bond with my students over the course of the three weeks.

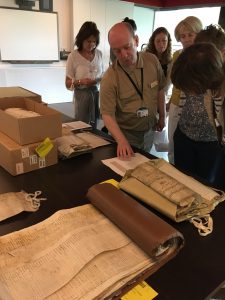

Creative experiential learning is still very much a possibility online. For example, the students and I visited Tate Modern virtually, exploring and engaging with their artwork on feminism which is accessible on their website. Even more importantly, the module benefited from a large number of brilliant guest speakers, both researchers at King’s lecturing on their areas of expertise, as well as journalists based in India and Paraguay – many of whom would not have been able to join us without online technology. As such, students got to experience London and the research community at King’s, as well as forming connections across a diverse group and participating in stimulating discussions. Whether online or not, this is what makes a great summer school experience.