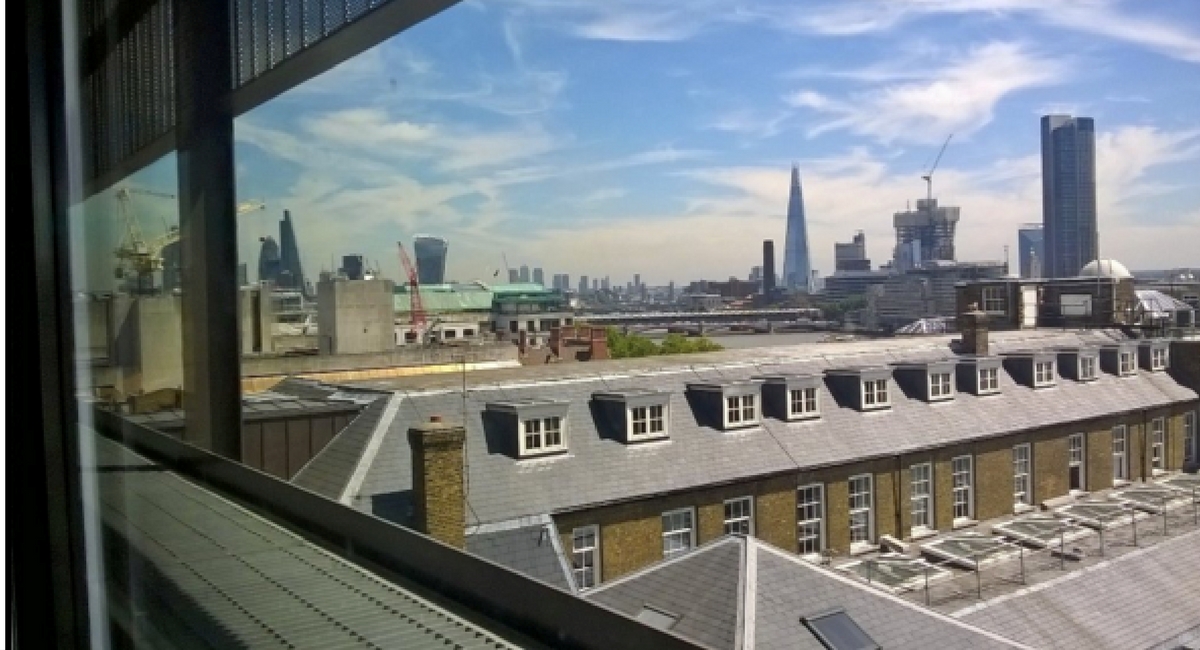

My experience as a tutor with the King’s Undergraduate Summer School programme is very much a privileged one. Each year I am fortunate enough to return to meet a new batch of extremely talented students, who have travelled from all over the world to come to study at the college. Their level of enthusiasm and willingness to explore every crevice of a London that will be there home for 3 (and sometimes 6) weeks never ceases to amaze. Every new class is a force of nature, and it is a pleasure to see individuals forge new friendships against the backdrop of this great city, many often returning over the subsequent months to reacquaint themselves with their favourite landmark, outdoor park or coffee shop. For my part, my Summer School experience allows me to indulge my love of cinema and my home city by teaching the popular London and Film course. This class starts on the big screen and moves outwards, examining London’s “cinematic” qualities and the many forms that it takes across a range of films. Sitting right on the Thames and within walking distance to its most famous landmarks, King’s College’s is the perfect place to map the capital’s shifting cinematic landscape, and to see how it has been portrayed by a host of homegrown and international filmmakers.

However, not only does the London and Film course offer an introduction to London’s cinematic history, or give an insight into the capital’s vibrant film culture (with the Cinema Museum, British Film Institute and London Film Museum all close by). This is a course that has also actively shifted the direction of my own teaching and research. The London-focus of the module’s case study films has broadened my own intellectual horizons and introduced me to new hidden gems that I am able to combine with my undergraduate and postgraduate courses. Guided by the knowledge of the Summer School students who bring the names of their favourite London-set films with them as they enter the college for the first time, I now seek out unknown and sometimes lost London titles. It is these odd and offbeat titles that find their way into courses I continue to teach here at King’s, their presence on modules a testament to the input of past Summer School students whose passing comment about ‘that film set in Covent Garden’ thankfully left an enduring imprint.

The global reach of the Summer School attracts students with their own diverse ideas of an imaginary London dreamt up in the media. My London is not your London, and while we may all share a romanticised idea of what the capital might be (home to James Bond, Mary Poppins and Bridget Jones perhaps), each film and each student has the potential to remake the city anew. Perhaps expectedly, I have lost track over the number of discussions I have had with my Summer School classes over whether it is the Harry Potter version of London, or the one glimpsed in Love Actually, that is more accurate and appealing. With this year’s Summer School 2017 fast approaching, it will soon be time to have these debates all over again. And I can’t wait.

By Dr Christopher Holliday

Back in 2009, King’s College London took the then courageous step to begin an Undergraduate Summer School. It was a leap in the dark and we started from nothing. At the time, the expectation was, quite unsurprisingly, that this was mainly going to be a programme for the North American market to suit their study abroad needs. In that first year our most important course was Shakespeare in London. Much has changed since then.

Back in 2009, King’s College London took the then courageous step to begin an Undergraduate Summer School. It was a leap in the dark and we started from nothing. At the time, the expectation was, quite unsurprisingly, that this was mainly going to be a programme for the North American market to suit their study abroad needs. In that first year our most important course was Shakespeare in London. Much has changed since then.

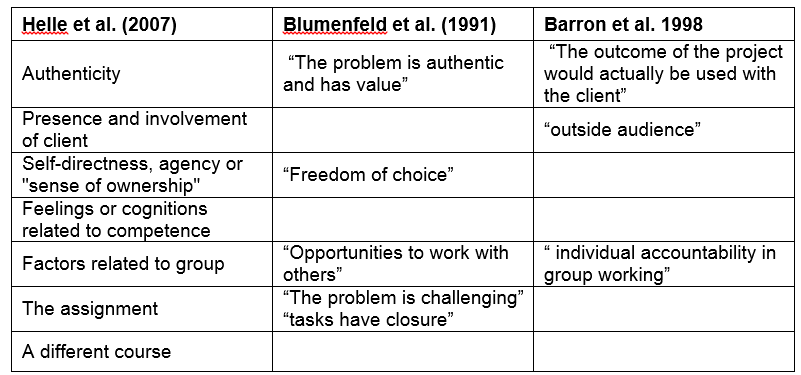

At the same time, the Finnish study found that there two project teams sometimes felt pressured by having to meet the expectations of the client and tackle a real-world problem [that they may see as intractable]. It is here where support from the instructor/advisor is key providing context, encouragement and helping the students focus on achievable goals and maintaining a good working relationship with the client.

At the same time, the Finnish study found that there two project teams sometimes felt pressured by having to meet the expectations of the client and tackle a real-world problem [that they may see as intractable]. It is here where support from the instructor/advisor is key providing context, encouragement and helping the students focus on achievable goals and maintaining a good working relationship with the client.

As we said farewell to the 255 high school students who joined us this summer for the Pre-University Summer School it struck us once again how dramatically the programme has grown since its inception in 2013.

As we said farewell to the 255 high school students who joined us this summer for the Pre-University Summer School it struck us once again how dramatically the programme has grown since its inception in 2013.