Dr Nicola Kirkby is a ‘Literature in the City’ tutor on King’s Undergraduate Summer School.

In SummerTimes she is sharing her observations as an academic who this year taught on a summer school for the first time.

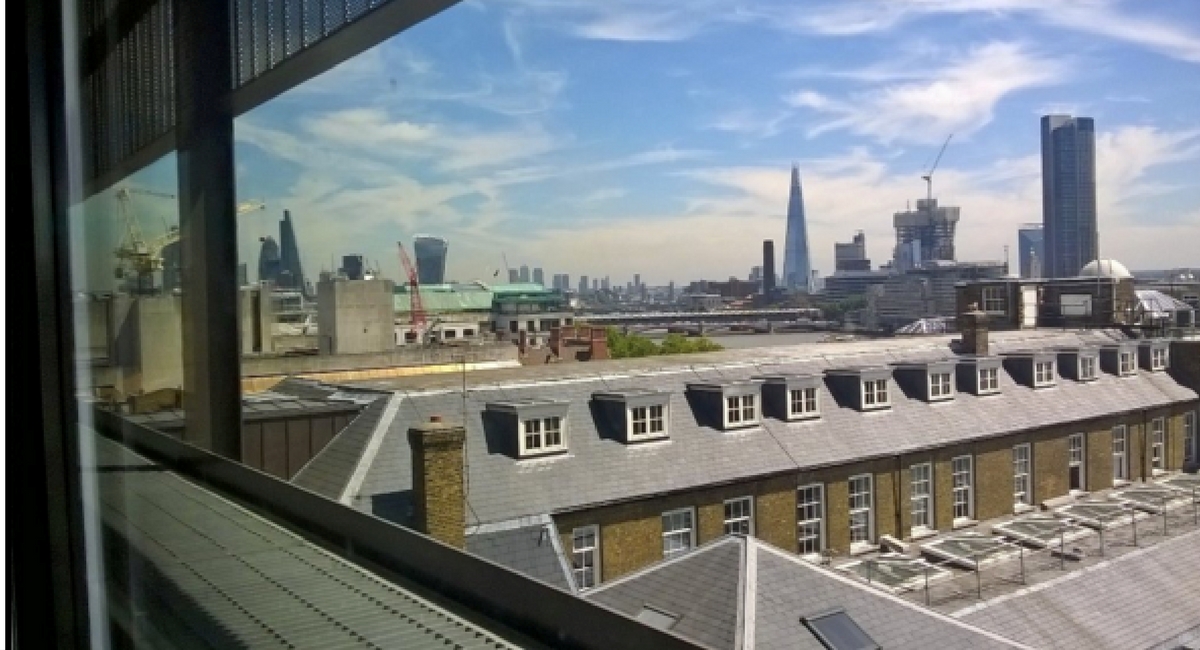

It’s a habit among critical thinkers to look for comparisons and contrasts. Throughout the King’s Summer ‘Literature and the City’ module, I prompted my students to explore differences between urban and rural experience, between London and their home town, between Dublin in the 1900s and Paris in the 1920s. From a pedagogical perspective, I was also drawing my own comparisons. Having taught a similar module, ‘Writing London’ in the Department of English at King’s for several years now, I found leading this summer school course for the first time in 2018 a refreshing counterpoint.

How do summer school cohorts differ from their term-time counterparts?

While there is much overlap (these are high-achieving undergraduates and alumni from universities across the world), I found that our lectures, seminars, and site visits had their own distinct dynamic that has impacted my teaching practice all year round.

Curiosity

Because they are open to students from any academic discipline, one of the most significant unifying pre-requisites for King’s Summer Programmes participants is curiosity about the course itself. English Literature majors were working alongside scholars with backgrounds in psychology, policy, modern languages, health science, and physics. This was invaluable in a course that interrogated what it means for people from all walks of life to live intersecting, interconnected lives. Our discussions may have focused predominantly on London, but such diversity in approach and experience meant that we were always bringing this city into dialogue with other global capitals, other networks, and other ways of understanding and organising shared space.

Thanks to such curiosity, the Summer School provided an ideal environment for exploring experimental ideas. At first, I think that students coming from more didactic learning environments found opportunities to challenge established theoretical approaches a little disorientating. But this approach fits well, both with the primary aim of literary studies: to encourage independent critical thinking, and with summer school learners themselves, who, in their choice to up sticks and study overseas for three-to-six intense weeks are more than equal to taking initiative.

Commitment

There’s nothing quite like leaving your life behind to embark on a few weeks of focussed study in a new place. Attendance throughout the summer school was sky-high in a way that is unparalleled in full-year courses where students often juggle responsibilities to home and work throughout the teaching semester. What I had not anticipated, and what I was utterly delighted to find was the tireless motivation of this group in our daily seminars, lectures, and site visits to places have changed London’s literary landscape. ‘Literature and the City’ is a fast-paced and thought-provoking module, and this year’s cohort impressed me by exploring London, Paris, and even Dublin on their own alongside our Monday-Friday classes.

Togetherness

The final distinction is a simple yet important one. Working alongside one another in an intense, discussion-led course helps summer school students build collaborative closeness in a way that would take much longer in a regular undergraduate module. By the end of the programme my ‘Literature and the City’ cohort had expanded their network, forging lasting connections with peers from across the world.