Dr Huw Dylan is a Senior Lecturer in Intelligence Studies and International Security in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. Dr Dylan is also a Visiting Research Professor at the Norwegian Defence Intelligence School, Oslo.

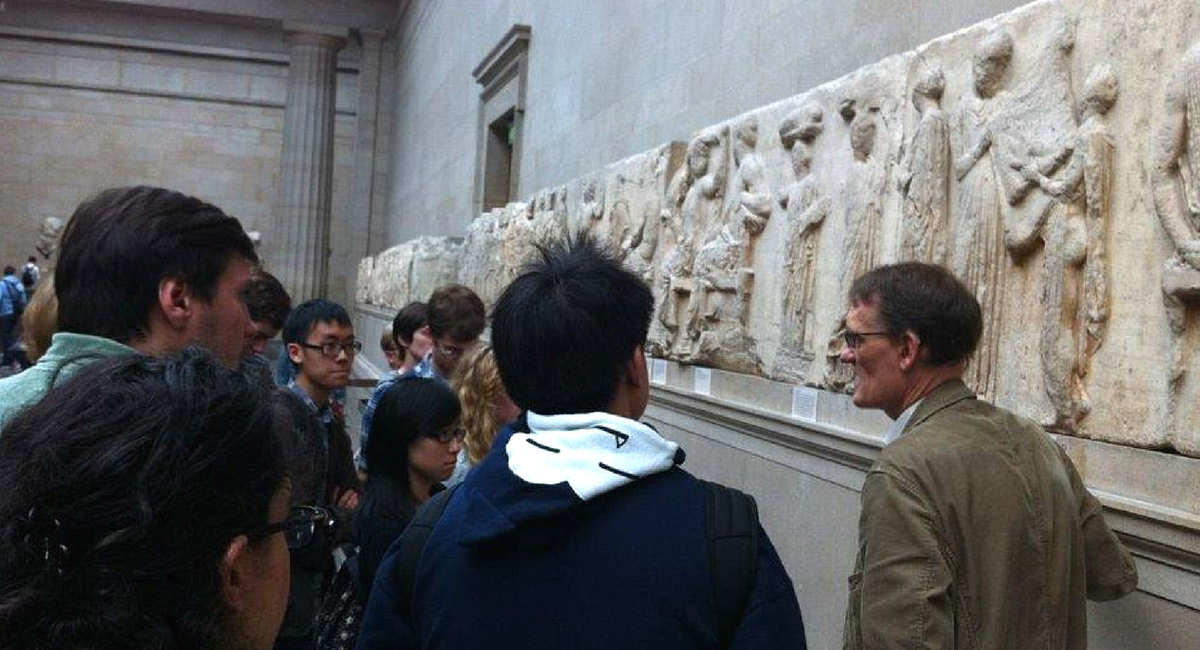

One of the most exciting things about the King’s Undergraduate Summer School is the variety of approaches to teaching and learning that students will experience. This reflects both the scope of subjects on offer, but also the energy tutors put into creating engaging learning environments. This entry, building upon our colleague Dr Diana Bozhilova’s blog post on teaching international relations in this series, offers a brief introduction to our approach to teaching Politics and the Media.

For those of us interested in politics and international relations it seems that not a day goes by without some controversy or other concerning what is the truth of a particular situation making the headlines in the press. From the competing narratives offered to the electorate in the BREXIT referendum, to the myriad debates concerning President Trump and words and deeds, to the running series of debates between Russia and the West over a number of issues, including the shooting down of MH17 to Russian involvement in east Ukraine, matters of strategic communication, allegations of propaganda, and charges of ‘fake news’ have come to dominate several areas of our political discourse. This course aims to place many of these issues in a deeper historical context, and to consider carefully how information and messages have been utilised by political power throughout history to further their goals.

Our teaching is based on our experience in the Department of War Studies. This department encourages an interdisciplinary and creative approach to studying conflict and war and all associated phenomena. We aim to combine teaching of core concepts and ideas, such as exploring the main theorists or thinkers of propaganda and strategic communications, in tandem with the conflicts or issues that they sought to influence at the time. And then to examine how these ideas resonate today in our contemporary debates. So, we will begin with the ideas of Gustav le Bon, and propaganda in the age of the Two World Wars, before moving on to the Cold War and the post 9/11 world. Students will engage deal with theory and practice, setting the scene for many of the issues we the class will consider during the latter part of the course.

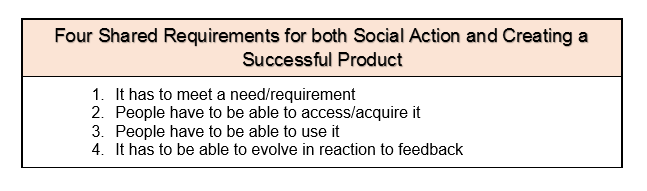

The learning outcomes for this short course on Politics and the Media are centred upon the development of an understanding of key subject matter and fostering critical thinking. The class will consider the core components of propaganda and strategic communication narratives in various case studies. Many of these case studies involve campaigns that aimed to convert or entrench the political stance or the voting intentions of a large body of people, and have become contentious. Analysing the construction, delivery, and impact of these various campaigns will leave students equipped to more effectively engage with such campaigns in future, in particular with regard analysing and challenging the competing claims of ‘truth’. A key component of developing these critical skills will be an active consideration of the modern information environment and information technology, and how they both facilitate the propagation and the challenge of key messages.