Dr Fiona Haarer, FSA

The Classics Department has a long tradition of running Summer Schools. For over forty years, we’ve hosted (in alternate years with UCL) the London Summer School in Classics and we usually get about 250 students of all ages. But though the students could study Greek or Latin at any level, the course lasts for only eight days, and UK students were forced to travel to Cork or the States if they wanted a comprehensive summer course which allowed them to go from complete Beginners to being able to read simple texts in the original. And so, with opportunities for studying Ancient Greek and Latin at school in decline (although happily the trend is now turning for Latin), we realised we should offer BA, Masters and Doctoral students and newly qualified teachers the opportunity to use their summer to make up some of this gap. So we organised a six-week course, which could be taken in two halves, Beginners and Intermediate, allowing students to take just the first period, or to join half way through.

We were delighted to offer Ancient Greek and Latin to just half a dozen students as part of the first cohort in 2010. This year nearly fifty students enrolled. As in previous years they came from a wide range of countries including Australia, Brazil, China, India, Japan, Norway Singapore, Sweden, Taiwan, the USA and many parts of Europe, with a wide range of educational backgrounds, and many with the additional challenge of learning an ancient language via a language which is not their first. Last year saw the introduction of another initiative: the use of the Intermediate courses to allow Classics Department students who have no previous knowledge of Greek and Latin to achieve a Classics degree by using the summer school courses to accelerate their language learning. Several students have chosen this Access Pathway and it has allowed King’s to follow Oxford, Cambridge and other Russell group universities in widening access and making it possible for students with no A Level in Greek and Latin to graduate with a Classics degree.

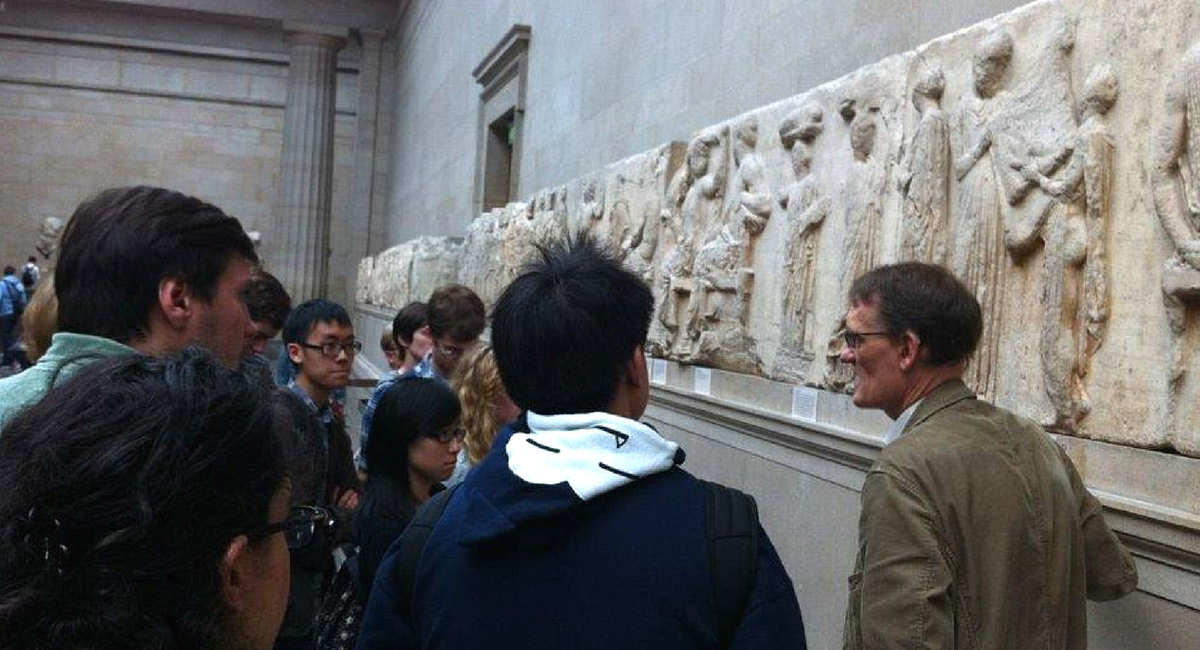

Although the Undergraduate Summer School courses are intensive in name and by nature, there is still time for extras. We offer lectures on key skills such as epigraphy and papyrology from visiting experts, and arrange ‘behind the scenes’ visits to the British Museum, where the students enjoy guided tours by curators, and an introduction to the research activities of the Departments of Greece and Rome, and Coins and Medals. A variety of learning environments and instructors allows the students to put their new language skills into practice, puzzling over inscriptions, legends on coins, and papyri.

The Ancient Languages students are a little different from the standard profile of the Summer School student. Some are taking the course for credit, some hold offers from their own universities which depend on successful completion of the course, some know that they won’t be able to read the relevant texts for their PhDs if they can’t master the language: they all come to King’s to work seriously and are therefore less attracted to the general summer school experience. On the other hand, this encourages a close and supportive esprit de corps within the classes as they bond over the experience.

If you want to learn a language you need a lot of concentration and consolidation, diligence and determination. To cover the same material in six weeks that regular courses would cover in a year or two needs an even greater degree of dedicated hard work and, while some struggle, the numbers who achieve high marks are impressive. It is also a testament to expertise of the team of language tutors, some of whom have been teaching these courses since 2010.

Finally, we are very grateful to the Classical Association which offers a grant every year to allow us to provide bursaries to students with particular financial hardship. In the discipline of Classics and the study of the Ancient World, we must we offer students every opportunity to acquire language skills, and the King’s College London Undergraduate Summer School is a great way to do this.

Back in 2009, King’s College London took the then courageous step to begin an Undergraduate Summer School. It was a leap in the dark and we started from nothing. At the time, the expectation was, quite unsurprisingly, that this was mainly going to be a programme for the North American market to suit their study abroad needs. In that first year our most important course was Shakespeare in London. Much has changed since then.

Back in 2009, King’s College London took the then courageous step to begin an Undergraduate Summer School. It was a leap in the dark and we started from nothing. At the time, the expectation was, quite unsurprisingly, that this was mainly going to be a programme for the North American market to suit their study abroad needs. In that first year our most important course was Shakespeare in London. Much has changed since then.

At the same time, the Finnish study found that there two project teams sometimes felt pressured by having to meet the expectations of the client and tackle a real-world problem [that they may see as intractable]. It is here where support from the instructor/advisor is key providing context, encouragement and helping the students focus on achievable goals and maintaining a good working relationship with the client.

At the same time, the Finnish study found that there two project teams sometimes felt pressured by having to meet the expectations of the client and tackle a real-world problem [that they may see as intractable]. It is here where support from the instructor/advisor is key providing context, encouragement and helping the students focus on achievable goals and maintaining a good working relationship with the client.