Dr Brian Wallace teaches two modules on British governance to South Korean and Mexican students on King’s Summer Programmes.

This July, King’s College London Summer Programmes hosted students from Mexico and South Korea for parallel courses on governance in the United Kingdom. A highlight of both courses was a joint session between the two cohorts, in a cultural exchange to facilitate reflection on the themes they had been exploring. One of the key aims of both programmes is encouraging students to use our learning sessions and the experience of residence abroad as a vantage point from which to consider their home countries via a series of themes applicable across borders. The students could both reflect on what they had learned about Britain and apply these reflections to their respective homes.

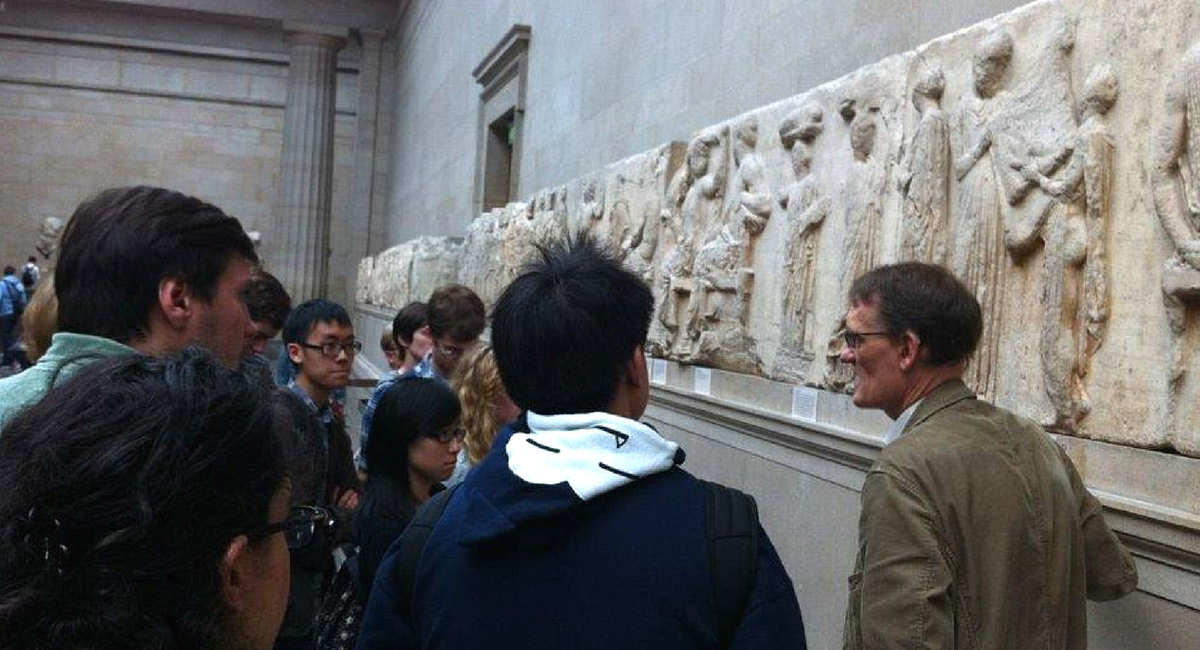

The session was designed primarily to spark dialogue and the exchange of ideas and experiences among our six mixed student groups, each composed of five South Korean and four Mexican students. After a brief introduction laying out their shared course themes and the shared London experiences they had all likely been encountering as tourists, our first ice-breaking conversation session asked the students within their groups to simply introduce themselves, their home town or city, and their favourite or least favourite thing about London. Our second strand explored the idea of common ground. Drawing on the ‘cultural exchanges’ theme, I gave our students a brief presentation on cultural and political links between Britain and their home countries, introducing cultural products such as art and food along with official occasions such as state visits, with their political rhetoric stressing the shared history and values of the nations. The second breakout conversation session asked the students to respond to this idea of common ground – was this reflected in their experiences visiting London? Did they feel their nation’s culture was familiar in Britain? What were the greatest similarities and differences? As these discussions were ongoing, I toured each group’s table and sampled their conversations and conclusions. There was a wide range of opinion, but one common theme which emerged among the students was interest in the ‘export versions’ of their national cultures they had encountered in London.

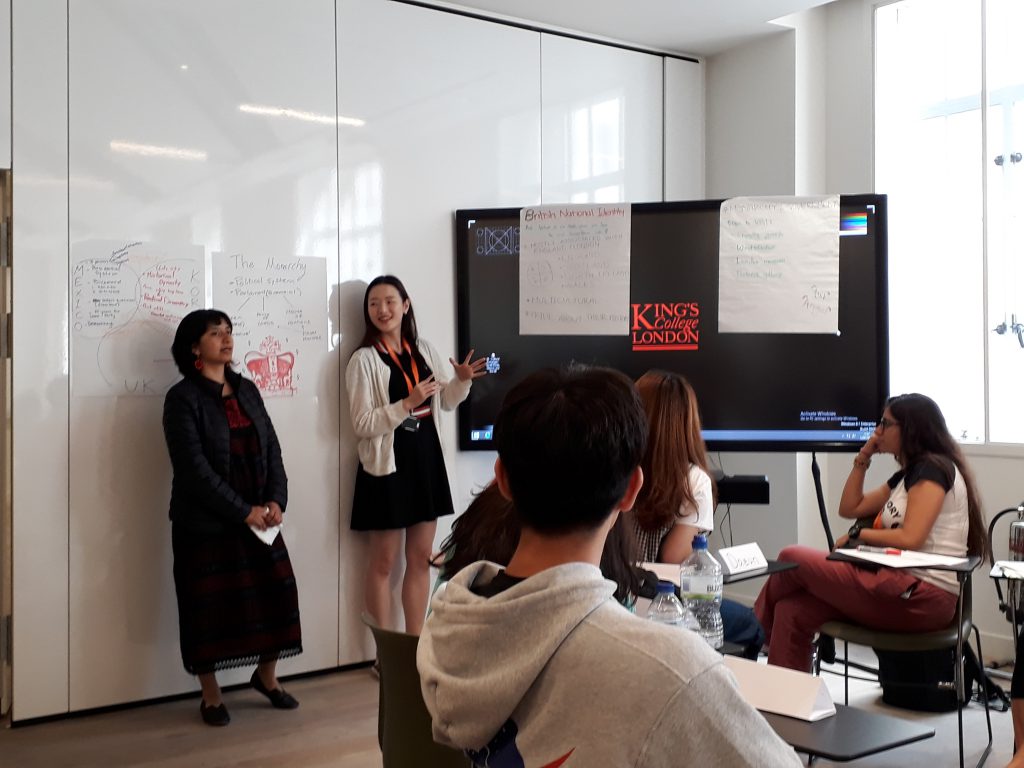

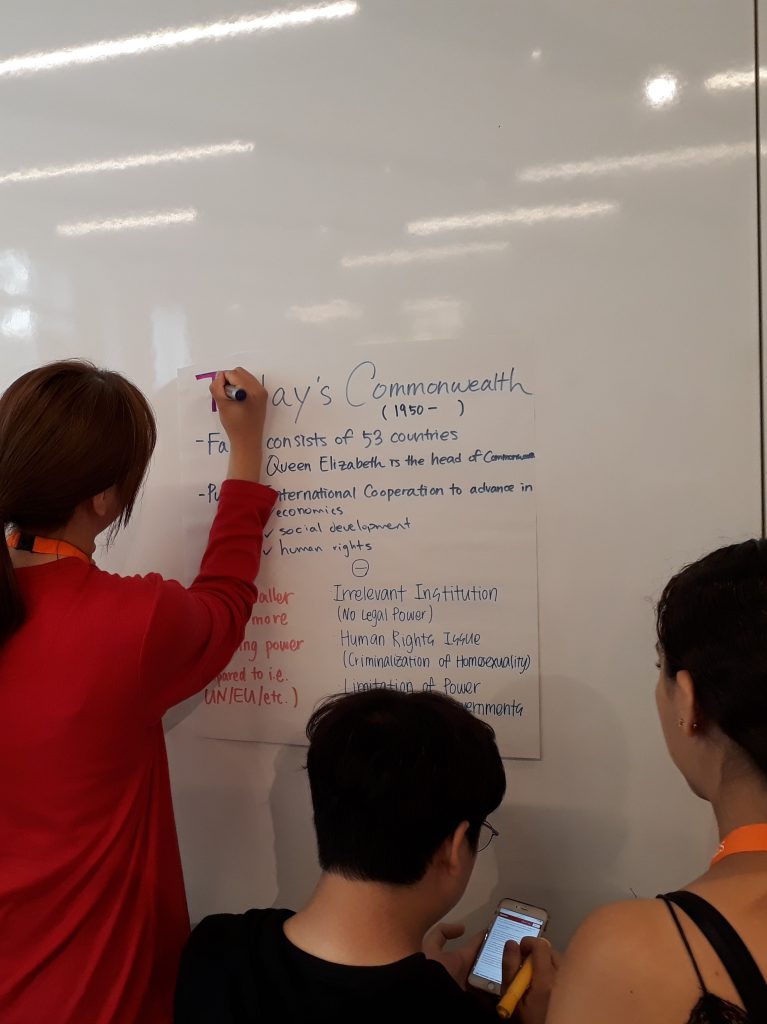

Our final conversation session asked the students to produce a more formal response in the form of a lesson plan poster presentation. Each group was assigned one of the common themes of the two programmes – national identity, monarchy, the empire and Commonwealth, government and Brexit, the British press, and cultural ‘soft power’. We then asked them to take on the role of teachers, composing a lesson for their fellow students back in Mexico and South Korea. How would they explain these themes? What case studies, objects, or sites would they use? What did they think their students would find most surprising about these themes in Britain? With one Mexican and one South Korean ‘teacher’ as co-presenters, the session encouraged students to not only demonstrate the knowledge they had acquired in our learning sessions, but to translate it for a home audience as well as considering it in an international context. The student groups responded creatively and thoughtfully, using diagrams and illustrations to lay out the similarities and differences between the three nations. Common features between the three nations were identified in the shared structures of government, while the greatest differences were identified in the realms of journalism and soft power.

The idea of cultural exchange is central to the aims of our summer courses and this session proved to be an invaluable venue for putting it into practice, offering a space for our student cohorts to respond to the themes of the course and give their own reflections on their London experiences. At the culmination of our students’ learning sessions on British themes, it productively reversed the student-teacher roles and encouraged them to discuss and delineate how these issues resonated at home. Finally, introducing the Mexican and South Korean cohorts to each other in order to engage in this reflective work generated a creative energy and excitement within the session which was reflected in the enthusiasm of their conversations and presentations.