King’s College London is a “research intensive” university. That means that in the Film Studies department we are not only using books, articles, documentaries, conference proceedings etc in our teaching, we are producing all those things – we are shaping Film Studies education here and at other universities around the world. It also means that you will be taught a dynamic and always developing curriculum that reflects our ever-expanding understanding of cinema as an art form, as an object of theoretical study and as an industry at the centre of moving image culture for well over 100 years. Every single one of your lecturers at KCL will bring the passion and unique insight gained from being top-level researchers to their teaching and we have experts in a very wide range of areas: film philosophy, film history, East Asian cinemas, American independent and exploitation cinema, global cult cinema, animation, horror, musicals, artists’ film and video, European art house and popular cinemas… and so much more! You can see this reflected in our diverse and always changing range of modules. Below, two colleagues present a couple of examples of their online, open access research and say a little bit about how it relates to their teaching.

Elena Gorfinkel

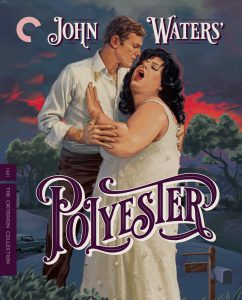

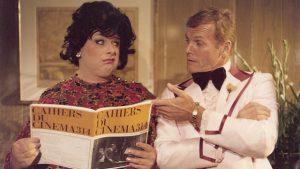

In my second year module “American Independent Film”, which explores US indies from the 1980s to the present, we examine how the core notion of the “independent” as an industrial and aesthetic category of filmmaking emerged from the work of directors who toiled on the studio’s margins. No better exemplar exists than John Waters, whose 1981 crossover comic-melodrama Polyester heralded the cult film and midnight movie crowd coming to the multiplex, in his scratch-and-sniff ode to Sirkian weepies and late 1950s experiments in sensory stimulation like Smell-o-Vision. The film anchors the beginning of the module and generates a variety of lively discussions with students each year, as we think about the changes in US film production and exhibition, the shift in Waters’ film style and generic form, and the legacy of midnight movies for 1980s independents. Sincerity and irony, camp and melodrama are a heady brew: is Divine’s rendition of Francine Fishpaw an empathetic character, an object of debased derision or a figure for something entirely and excessively otherwise? Teaching this film only solidified my devotion to the subversive queerness of Waters’ cinema. Thus, I was delighted by the opportunity to write about Polyester for the Criterion Collection restored re-release of the film on Bluray and DVD.

Film criticism, while very different from scholarly writing, represents a way to sharpen and widen one’s research interest at the same time. It also provides space for the pleasures of close reading for a broader audience. Informed by my experience of analysing the film with students at King’s, the essay allowed me to extend questions that are central to my scholarly interests around marginal and adult cinemas (in my work on the sexploitation film of the 1960s and underground film), gender and sexuality in film history, cinephilia and alternative spaces for film community, and the embodied nature of film-going – its marshalling of affects and senses, including smells! I only hope that next time we screen Polyester in the module, I am able to nab some proper scratch-and-sniff cards for the full Odorama experience.

Jeff Scheible

I teach a second year module called “Race, Cinema, and American Culture”. The history of American cinema, students learn in this module, is impossible to disentangle from the history of the ways in which tensions around race have shaped American life. We examine these intertwined histories in filmmaking practices spanning more than a century—covering silent films and the transition to sound in the 1920s, Hollywood’s “social problem films” of the 1940s, blaxploitation movies from the 1970s, and documentaries, artists’ films, and music videos made in the early 21st century. (Yes, we even study Beyoncé’s Lemonade.)

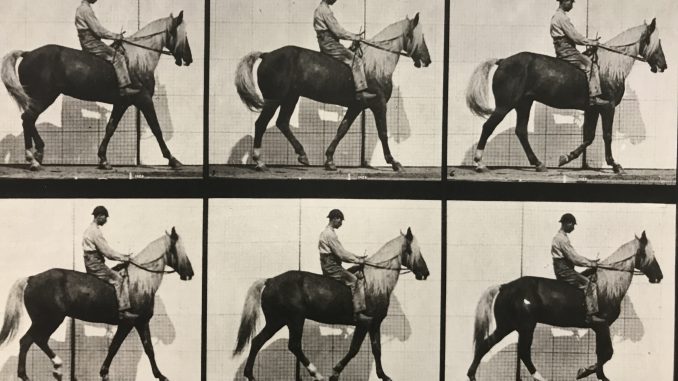

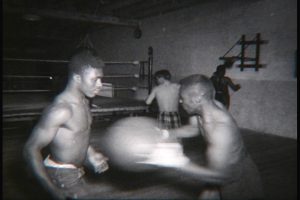

A few pivotal moments in early nonfictional filmmaking we study in the module revolve around athleticism: recordings of boxing matches from the 1910s and pre-cinematic studies of human motion that are said to have paved the way for the emergence of cinema. Their fascination relies on issues of racial difference. At the same time that I was teaching these histories, students joined me at the nearby TATE Modern for a weekend-long, mid-career retrospective of films by the artist Kevin Jerome Everson, whose captivating short films we also watch in the module.

I was struck by the ways in which Everson’s films repeatedly return to themes and images of black athletes (cowgirls, race-car drivers, boxers, water-skiers, and many more) and how some aspects of his filmmaking at the same time stylistically recall early cinema.

I used this observation as a starting point to write an essay about race, athleticism, documentary, and Everson’s films for the documentary journal World Records. I was excited to contribute to the journal not only because of their fantastic online layout but also because it is part of a special issue they were doing on African American documentary—a topic about which, I realised through teaching this module, there remains a lot more to explore.

Read More:

To read more about the student experience, you can check out Jack’s Top 5 Things I Love About Film Studies, and Liv’s Day in the Life of a Film Studies Student.

For more information on the Film Studies department, click here.

Leave a Reply