By Chiamaka Nwosu, Data and Research Analyst |

Are universities relying on inadequate data to understand the progression and success of students from ethnic minority backgrounds? Chiamaka Nwosu argues that we need better data to allow for more rigorous analysis of the ethnic attainment gap.

When considering the various forms of disadvantage that hinder potential students from accessing higher education (HE) and subsequently, from achieving “good” i.e. first or upper second-class degrees, ethnicity is usually lumped together with other indicators like disability, care experience, neighborhood characteristics like Participation of Local Areas (POLAR) and the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). However, ethnicity is not clearly a disadvantage, rather it is typically used as a proxy for other kinds of disadvantage, especially economic disadvantage.[i] For instance, a large proportion of refugees and asylum seekers are from ethnic minority groups. Similarly, having English as a second language is typical of non-White students. Thus, while these two concepts are correlated, this does not necessarily imply causation. Interestingly, the Educational Endowment Foundation (EEF) report[ii], which details important information on pre-university attainment gaps does not mention ethnicity but focuses instead on eligibility for Free School Meals (FSM) as a proxy for disadvantage. However, potential problems with using FSM arise because students move in and out of eligibility over time, and this fluctuation in their levels of deprivation may influence their attainment at school. [iii]

Using Ethnicity for Contextual Offers

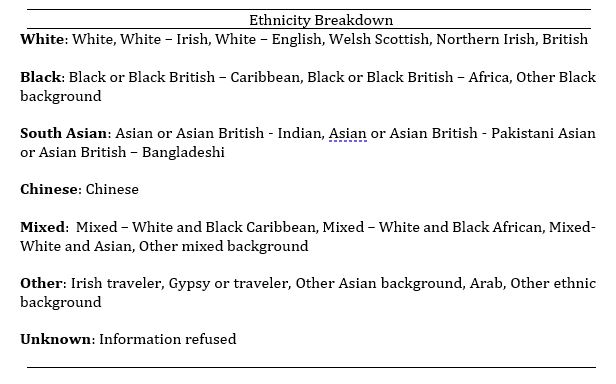

Information on students’ ethnicity is not normally available to universities at the time that admission decisions are made, and thus may not be useful for making contextual admission offers. Also, since ethnicity is self-reported, it is subject to an individual’s own interpretation and sense of belonging to a particular group. In addition, the number of options and categories are ever growing and as such, it has become increasingly difficult to define one’s ethnic group. In fact, statistics from UCAS show that the ethnic category with the largest share of students is the missing, refused or unknown group[iv]. This means that although ethnicity may impact attainment, it is currently quite difficult, if not impossible, to use ethnicity as a target indicator. The table below shows the broad ethnicity categories generally used in the UK and their composition.

Table 1 Ethnicity categories used in HE

Higher Education Participation Rates for Ethnic Minorities

On average, the Higher Education Initial Participation Rate (HEIPR) for ethnic minorities in the UK has been consistently higher than the HEIPR for White students for the last twenty years [v], which means that ethnic minorities are not necessarily the target group for WP initiatives unless they are also disadvantaged. However, Connor, et al (2004) show that many minority ethnic groups are still underrepresented at the most prestigious universities, particularly the Russell Group universities, while they are mostly overrepresented in the post-92 (i.e. new or modern) universities, especially those based in London. They are also more likely to enroll for certain courses at university such as computer science and medicine and less likely to enroll for degrees in the humanities because they prefer more traditional courses with defined career paths which provide more employment opportunities and reduced chances of racial discrimination [vi]. However, higher participation rates have not necessarily led to higher achievement for students in ethnic minority groups.

Attainment i.e. Good Degrees

Despite the higher HE participation rates for minority ethnic students, they usually achieve weaker degree results than White students. Black students are less likely to achieve a first class or upper second-class degree compared to White students and compared to other minority ethnic groups. However, the attainment gaps found between White and Chinese students are usually smaller. There are several possible explanations why this happens.[vii] One common one is that the high participation rate leads to the “more means worse” phenomenon,[viii] which implies that the standard drops because more minority students are applying to HE, which; all things being equal will increase the proportion of applicants who may not be qualified. The kinds of courses typically chosen by students belonging to minority ethnic groups may also play a part in the likelihood of achieving a good degree as they usually study courses where the shares of good degrees awarded are usually quite low to start with. The graph below obtained from HESA student records shows the proportion of UK-Domiciled qualifiers at UK Higher Education Institutions who received” good” degrees by ethnicity in 2017-18.

Table 2 Analysis of 2017-18 HESA student data record by Universities UK and NUS (2019)

Prior Attainment

A lot of the variation in attainment is due to the differences in initial tariff points. Since 2002, UCAS introduced a tariff system to allow comparisons between the various entry qualifications. This means that comparing qualifications before 2002 will be difficult as these tariff points would not be available. However, recent data shows that Chinese students tend to have higher tariff points upon entry to HE while Black students and students from other minority groups usually have tariff points at the lower end of the spectrum.[ix]

Prior attainment may also be linked to the route to higher education, which tends to be different for ethnic minority groups, compared to their White counterparts. It is not uncommon to find that most students from these minority groups enter HE through further education (FE) colleges rather than the more common A- level route, which tends to be the preferred route for highly prestigious universities such as Oxford and Cambridge. [x]

Boliver (2015) argues that students from minority ethnic groups who have good grades are still less likely to be offered places at university than White students who have similar grades, suggesting that racism may be present in the admissions process, considering that admissions staff are allowed to use their own discretion in making admissions decisions, particularly at the most selective universities.[xi]

Ethnicity and Social Class

Another common explanation given to explain disparities in attainment between ethnic groups is the difference in social class. For instance, Strand (2011) finds that while only 3 percent of White – British students came from families where the head of the household had never worked or was long term unemployed, this number was 26 and 40 percent for Black and Bangladeshi students respectively.[xii] Socio-economic disadvantages for students from working-class backgrounds can affect early development through lack of positive parental influence and aspirations, attending schools with limited resources, and lack of knowledge of the cultural practices most prized by the majority population[xiii], which may jointly contribute to low prior attainment for the most severely disadvantaged students.

For students from disadvantaged backgrounds in ethnic minority groups who achieve good grades that allow them to enter higher education, they may also encounter other roadblocks that prevent them from applying to the universities of their choice such as location and the ethnic mix at their preferred universities, they might be discouraged from attending universities where they are less likely to blend in, most likely the case with universities outside London which often have a less diverse student population[xiv]. Admission policies can be quite strict at certain universities and some universities even prohibit part time studies or working during term time which is common for a vast majority of ethnic minority students.[xv]

After enrolling at university, ethnic minority students who are also disadvantaged may find themselves facing a high level of financial difficulty due to not being able to pay for several things needed for their everyday life on campus. Some studies have found a negative association between financial hardship, working during holidays and academic attainment, particularly among students from single-family homes or those students who have larger families and several siblings.[xvi]

What Can We Do About the Ethnicity Attainment Gap?

Realizing that there is an ethnicity attainment gap is one thing, the next step is thinking about possible ways to tackle this gap. At What Works, we are running learner analytic projects to understand the impact of policies like contextual admissions and the use of predicted grades as a measure of ability to properly investigate the attainment gaps that exist at King’s College London. These studies might be hindered or limited in scope without access to good data. You can find out more about our work here. However, if as a sector we are committed to understanding and eliminating the gaps in university progression and degree awards that students from ethnic minority backgrounds, we need better data.

_______________________________________________________________________

Read our reports

Click here to join our mailing list.

Follow us on Twitter: @KCLWhatWorks

[i] Gorard, S., Boliver, V., Siddiqui, N., & Banerjee, P. (2019). Which are the most suitable contextual indicators for use in widening participation to HE?. Research Papers in Education, 34(1), 99-129.

[ii] https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Annual_Reports/EEF_Attainment_Gap_Report_2018.pdf

[iii] Gorard, S. (2016). A cautionary note on measuring the pupil premium attainment gap in England. British journal of education, society and behavioural science., 14(2), 1-8.

[iv] Connor, H., Tyers, C., Modood, T., & Hillage, J. (2004). Why the difference? A closer look at higher education minority ethnic students and graduates. Institute for Employment Studies research report, 552.

[v] Tatlow, P. (2015). Participation of BME students in UK higher education. Aiming Higher: Race, inequality and diversity in the academy, 10-12.

[vi] Connor, H., Tyers, C., Modood, T., & Hillage, J. (2004). Why the difference? A closer look at higher education minority ethnic students and graduates. Institute for Employment Studies research report, 552.

[vii] UUK & NUS. (2019). Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Student Attainment at UK Universities:# ClosingTheGap.

[viii] Richardson, J. T., Mittelmeier, J., & Rienties, B. (2020). The role of gender, social class and ethnicity in participation and academic attainment in UK higher education: an update. Oxford Review of Education, 46(3), 346-362.

[ix] Connor, H., Tyers, C., Modood, T., & Hillage, J. (2004). Why the difference? A closer look at higher education minority ethnic students and graduates. Institute for Employment Studies research report, 552.

[x] Connor, H., Tyers, C., Modood, T., & Hillage, J. (2004). Why the difference? A closer look at higher education minority ethnic students and graduates. Institute for Employment Studies research report, 552.

[xi] Boliver, V. (2015). Why are British ethnic minorities less likely to be offered places at highly selective universities. Aiming Higher: Race, Inequality and Diversity in the Academy. London: Runnymede Trust, 15-18.

[xii] Strand, S. (2011). The limits of social class in explaining ethnic gaps in educational attainment. British Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 197-229.

[xiii] Bourdieu, P (1984) Distinction Oxon: Routeledge

[xiv] Gamsu, S., Donnelly, M., & Harris, R. (2019). The spatial dynamics of race in the transition to university: Diverse cities and White campuses in UK higher education. Population, Space and Place, 25(5), e2222.

[xv] Boliver, V. (2015). Why are British ethnic minorities less likely to be offered places at highly selective universities. Aiming Higher: Race, Inequality and Diversity in the Academy. London: Runnymede Trust, 15-18.

[xvi] Scales, J., & Whitehead, J. (2006). The Undergraduate Experience of Cambridge Among Three Ethnic Minority Groups. The Cambridge Reporter.

Leave a Reply