By Salome Gongadze, Research Associate|

Here at What Works, we never miss an opportunity to insert a little behavioural insights experimentation into the rest of our work. Recently, we took the opportunity to experiment on a new group: King’s staff! This blog post shows how we took advantage of a need to send out a mass email to test framing effects for email communication.

We are choice architects in almost everything we do

If you think about it, opportunities to be a choice architect are everywhere. So many tasks we take on in our daily work at the What Works office present opportunities for us to apply what we know about behavioural insights to influence others’ choices in positive ways. This can be as simple as the seemingly-mundane office task of sending an email to somebody – in this blog, we present a neat example of how an understanding of choice architecture can be used in emails to successfully test behavioural insights in a cheap, quick-fire randomised trial.

This sort of trial can be done completely remotely, which is very useful for everyone in our current state! Although all of the university sector is working remotely now, we will show that it’s still possible to evaluate what we are doing.

We came upon this opportunity when we decided we would send out a mass email to staff in our directorate to encourage them to look at our newly-redesigned intranet pages, where we host briefings outlining our research into behavioural insights for higher education.

In order to insert some behavioural insights experimentation, we set up the email as an A/B test. A/B tests are a form of randomised trial in which subjects are randomly assigned into two groups (Group A & Group B), with each receiving a different variant of some variable. Practitioners then compare which variant did better on a predefined outcome measure (e.g. open rate).

For our A/B test, we wanted to test which type of messaging KCL staff in our Directorate were most receptive to.

Does changing the language of a staff email and subject line encourage more staff to open the email and click its link?

In our experiment, the participants were a group of 500 staff members in a directorate of King’s College London. The variable we changed was the description of the benefit of the information we were providing, reflected in the main text and the subject line of an email that encouraged staff to look at our redesigned internal intranet pages. These pages host our research briefings and guidance documents setting out best practice and the most recent research into applying and evaluating behavioural insights in higher education, like a guide to our ACES framework.

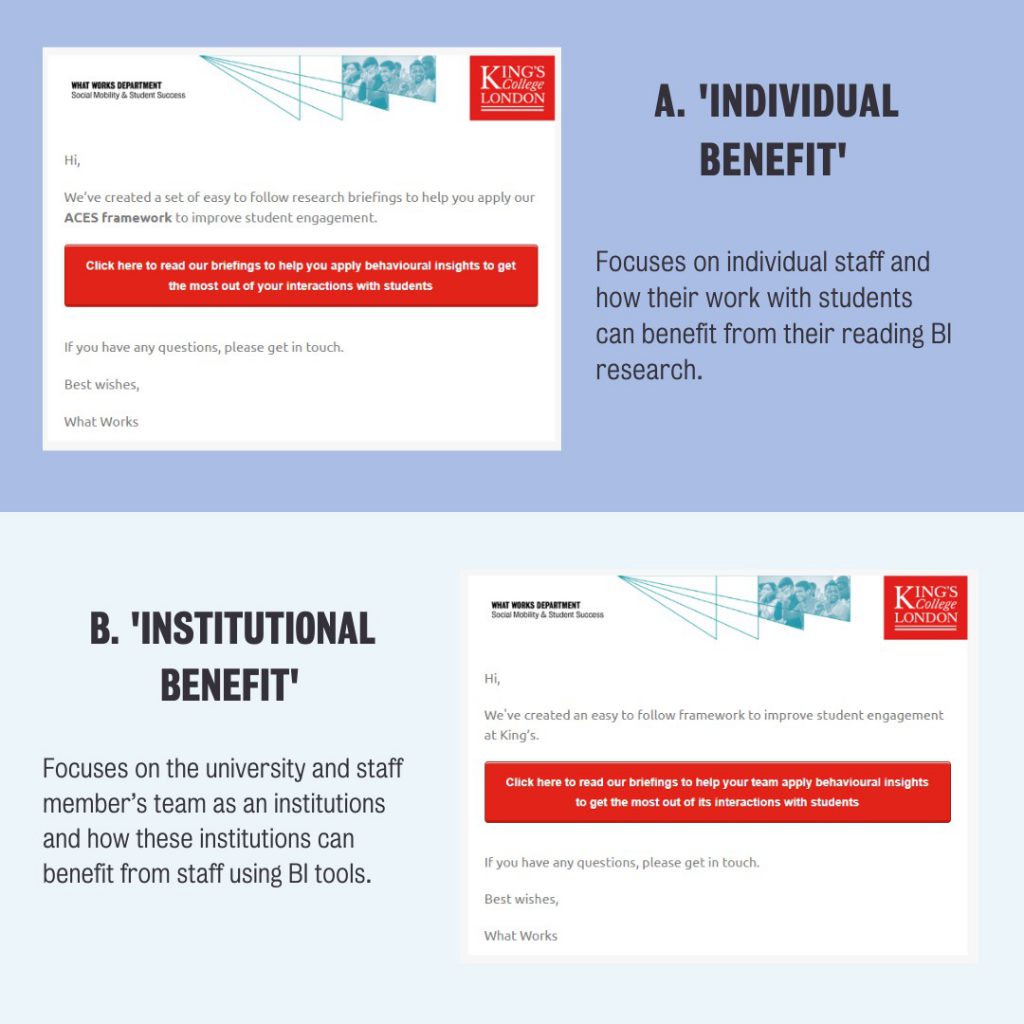

In order to test which out of articulating the benefit of engagement with the email as either institutional or individual would increase response rates we altered the email wording and subject line. We varied these to create two message frames as shown in the graphic above.

We then monitored open rates and the number of people, who after opening the email, then clicked on the link to see which email motivated the most action from our colleagues.

Our results: were subjects more motivated by group utility than personal utility?

Here’s a snapshot of the raw numbers on our results:

| Framing type and number of people who received this treatment:

|

Percentage and number of recipients who opened the email: | Percentage and number of recipients who clicked the link in the email after opening the email: |

| Individual benefit (237 staff members) | 33.76% (80) | 46.35% (37) |

| Institutional benefit (235 staff members) | 36.75% (86) | 54.65% (47) |

Although more people opened the ‘institutional benefit’ email and clicked the link within it relative to the ‘individual benefit’ email, the difference in engagement between the two groups was not statistically significant for either email opens or click throughs. In both cases the ‘p value’ (or probability value) is more than 0.05, which means we can’t discount that the difference between the two groups is down to chance (i.e. we can’t discount that there is actually no relationship to our variables and the outcome), as the probability of this being the case is more than 5 per cent.

Null results are still interesting. Given our colleagues were randomly sorted into two groups, it’s interesting that a similar proportion opened the email, and then a similar proportion clicked on the link. When testing future emails, we now have a good idea of what baseline engagement might look like for this kind of email. When we run similar interventions with students, we normally send our communications in the thousands, so an open rate of around 30 per cent would still give us a big sample.

Even when sending out a simple email, think about if there’s more you can do to make it impactful

Our experience of running this email-focused A/B test shows that RCTs and behavioural insights research do not have to always be big, long-term projects. In fact, they can be set up relatively easily, requiring in this case nothing but a contact list of staff participants and email campaign software that allowed us to track open and click-through rates. In the future, we can use this model to further explore if any behavioural insights can be utilised to increase staff engagement with communications.

Why have we told you about a failed experiment? It demonstrates you still learn when something doesn’t work. This example also shows the value of looking for opportunities to embed behavioural experimentation into more of the work we do. With a little creative thinking, we turned a business as usual email into experimental research and in doing so, added to our knowledge about staff engagement. No doubt, there are lots of opportunities for you to do the same.

_______________________________________________________________________

Click here to join our mailing list.

Follow us on Twitter: @KCLWhatWorks

Leave a Reply