By Lucy Makinson, Behavioural Insights Team |

I. The benefits of participation in student societies

Participating in extracurricular activities is an important part of being at university. It is an opportunity to meet other students, build social networks, and develop soft skills[1] which are often valued by employers and can improve labour market outcomes after graduation.[2][3] Participation can also improve outcomes within university by improving academic attitudes.[4][5]

In addition, being a part of a university club or society may enhance students’ sense of belonging within university which in turn has positive impacts for academic engagement and retention.

There is some evidence from the US that the benefits of campus participation are particularly significant for students from ethnic minority and low-income backgrounds.[6] However, a recent study from the University of Edinburgh found students from Widening Participation backgrounds are half as likely to hold positions in the university’s clubs and societies.[7] There may be several factors driving this – one is that students from low-income backgrounds are less likely to participate in extra-curriculars at school,[8] where they may have also had less extra-curricular provision,[9] with school participation being a good predictor of extra-curricular participation at university.[10] Another is that they may underestimate the benefits of participation, particularly in relation to employment outcomes.

II. The trial

The KCL Welcome Fair runs for three days at the start of the academic year and is an opportunity for students to find out about the clubs and societies available at King’s and sign-up to join them. We therefore wanted to encourage first year students to attend the Welcome Fair, with the final aim of increasing sign-ups to clubs and societies, using a series of messages in the run-up to, and during, the event. Although we considered participation a positive outcome for all students, we were particularly interested in the attendance and sign-up rates of students from WP backgrounds.

Designing the messages

From the existing research on student society participation, as well as the wider behavioural literature, we hypothesised three key reasons for why a student may not attend the welcome fair.

1. Lack of belonging

Students who feel uncertain about whether they belong at university may be more likely to rest on their academic success to justify their being there, and see extra-curriculars as a distraction. They may also be worried about attending the fair alone, possibly through a perception that other students already know each other

2. Lack of information

Students may not perceive either the social or career benefits of being part of a society. They may also be unaware of the range of societies available, and not know where to find societies which match their interests.

3. Lack of planning or priority

Students may not attend the welcome fair due to competing priorities, not feeling like going on the day, or failing to plan appropriately (for example, by not making a clear plan of when to go and making a note of it).

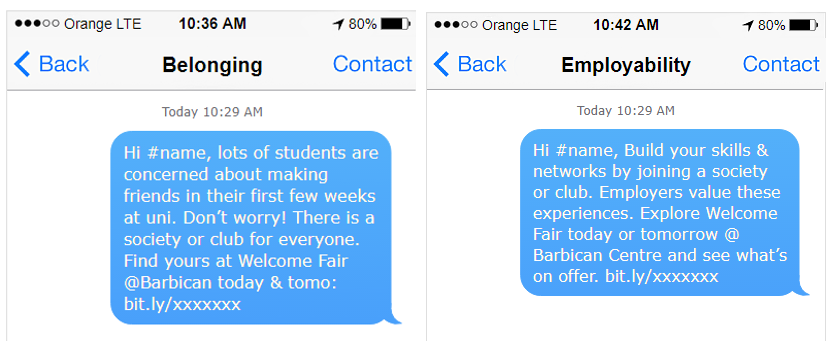

Based on these hypotheses we designed two different sets of messages. One focused on addressing barriers to belonging – reassuring students that it was normal to not know anyone when arriving at university and to feel overwhelmed, but presenting societies as an opportunity to meet other students to support them through the transition. The second focused on addressing informational barriers, in particular emphasising the positive impacts of society participation on employability as well as emphasising their social benefits. Both sets of messages also drew on the extensive literature surrounding planning prompts, and encouraged students to make a specific plan with a link to the Citymapper app to help them plan their route.

Trial design

The Welcome Fair ran from Friday 23rd to Sunday 25th September 2016. Ahead of this we randomly allocated[11] all first year students[12] to one of three groups.

The first (control) group did not receive any text messages about the Welcome Fair, although they would have received information about it through the existing communications with first year students.

The second (belonging) and third (employability) groups each received three text messages: the first message was sent the Monday before the Welcome Fair, 19th September; the second on Friday 23rd, the morning of the first day; and the final message was sent on Saturday 24th, the morning of the second day.

The messages for the ‘belonging’ group all focused on reducing perceived barriers associated with belonging, whilst those in the ‘employability’ group received messages emphasising employment benefits of societies and other informational failures.

The primary outcome measure for this trial was whether a student attended the Welcome Fair. Students entering the Welcome Fair swiped their KCL ID card in order to enter,[13] and this data was recorded by the King’s College London Student Union (KCLSU) and subsequently shared with BIT for analysis.

The secondary outcome measure was whether a student had signed up for at least one society, either at the Welcome Fair or later in the year (data was collected in July 2017). Again, this data was provided by KCLSU who record all sign-ups to student societies throughout the year.

III. The results

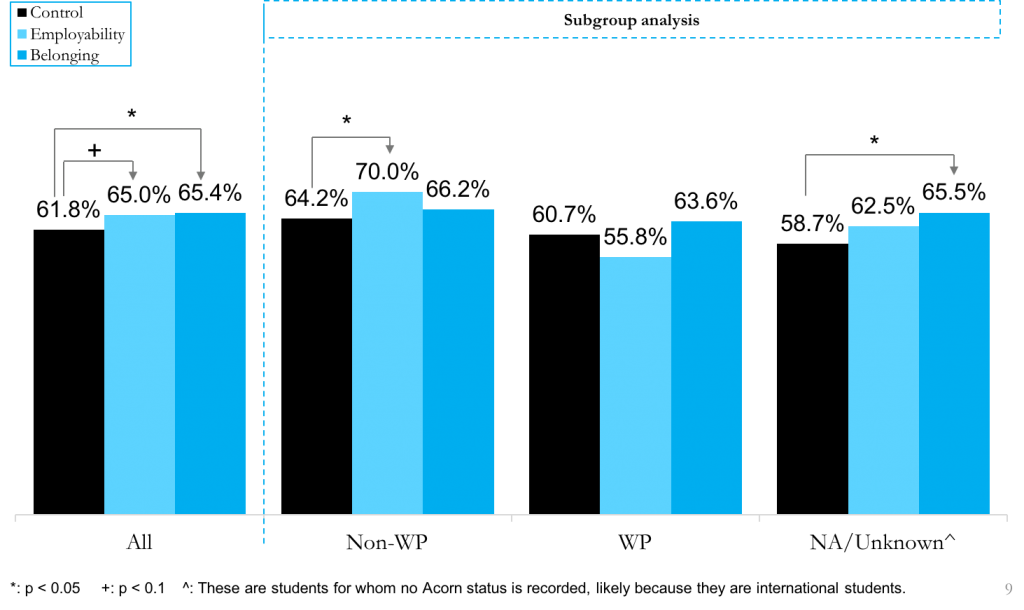

We found that the messages did make students significantly more likely to attend the Welcome Fair, although the most effective message appears to depend on student characteristics.

Looking across all students, the messages centred on belonging had the greatest impact on attendance, resulting in a 6 per cent increase. Employability messages, in contrast, increased attendance by just over 5 per cent, and the increase was not significant at conventional levels.

However, this trend was not true across groups. We conducted separate analyses for students in ACORN groups 1-3 which we used to define non-WP students, students in ACORN groups 4 and 5 which we used to define WP students, and students without an ACORN grouping within King’s record (these will be mainly international students).

Among non-WP students, the employability messages were the most effective and increased attendance by 9 per cent, while the belonging messages only increased attendance by 3 per cent which was not significant at conventional levels.

Among WP students, the belonging message appears to be more effective indicating an increase in attendance of nearly 5 per cent, while attendance among WP students in the employability group in fact had lower attendance than those in the control group (who had not received any messages at all). It is worth noting that these changes are not significant at conventional levels, but this will be partly due to the smaller sample of WP students.

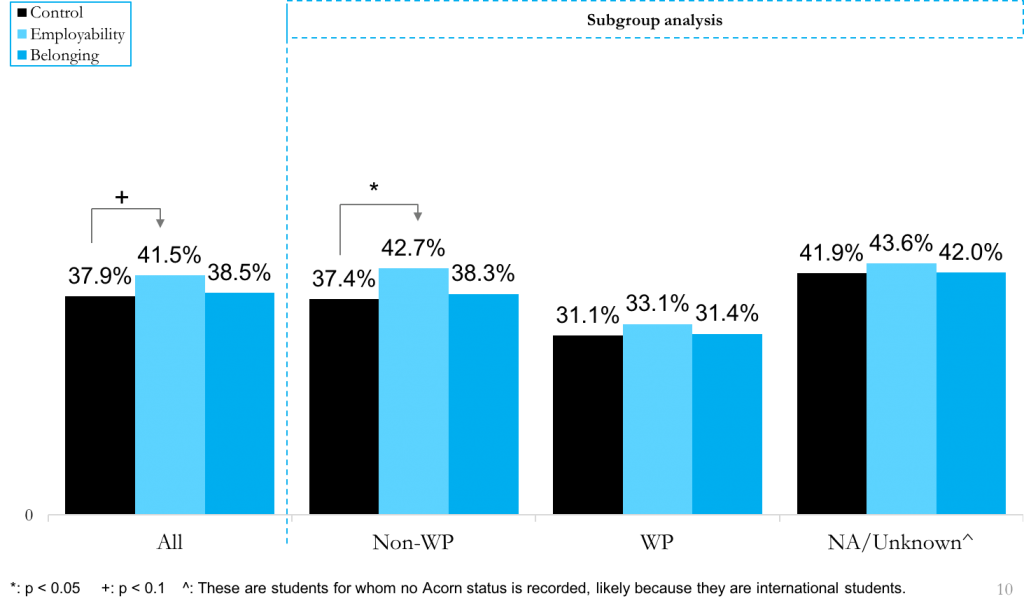

We can also look at sign-ups to societies, but this analysis comes with the caveat that it only includes societies who charge for membership (and hence are required to maintain a membership record with the Student Union). Several large societies are free, and therefore the data likely don’t represent a full picture of their membership. With that in mind, we find that the employability messages increased recorded sign-ups to societies but the belonging messages did not. This is true both at an aggregate level[14] and for non-WP students specifically.

This is interesting given that attendance was increased to a greater extent by the belonging messages. Particularly notable is that for WP students, although no sign-up effects were significant, sign-ups in the employability group were higher than the belonging group, despite belonging messages appearing to be more effective for attendance.

However, it is worth bearing in mind that WP students may have been more likely than non-WP students to join free societies (either because they were of more interest or because of the cost barrier), and therefore this data may be incomplete. Likewise, it may be that the belongingness messages made students to be more likely to join societies that tend to be free (identity/culture-based societies, for instance) rather than those that had a membership fee (such as sporting societies). Because our data are incomplete, the analysis above should be treated with caution.

IV. What we have learned

This trial has several important lessons for approaches to student engagement. Firstly, it demonstrates that text messages to students can be an effective mechanism for increasing engagement, both for one-off events (such as the Welcome Fair) and for harder to shift outcomes such as participation in clubs and societies.

However, it also demonstrates the importance of good design and rigorous testing when creating engagement initiatives. Not only did responses to the messages differ by group, which means the results of this trial can be used to improve the targeting of messages in the future, but the fact that messages around employability may have decreased attendance for WP students is evidence that texts in and of themselves may not always increase a prompted behaviour.

Click here to join our mailing list.

Follow us on Twitter: @KCLWhatWorks

_________________________________________________________________

Footnotes

[1] Clark, G., Marsden, R., Whyatt, J.D., Thompson, L. and Walker, M., 2015. ‘It’s everything else you do…’: Alumni views on extracurricular activities and employability. Active Learning in Higher Education, 16(2), pp.133-147.

[2] Andrews, J., & Higson, H. (2008). Graduate employability,‘soft skills’ versus ‘hard’ business knowledge: A European study. Higher education in Europe, 33(4), 411-422.

[3] Stuart, M., Lido, C., Morgan, J., Solomon, L. and May, S., 2011. The impact of engagement with extracurricular activities on the student experience and graduate outcomes for widening participation populations. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12(3), pp.203-215.

[4] Fredricks J.A., and Eccles J.S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42(4): 698–713.

[5] Darling, N. (2005). Participation in extracurricular activities and adolescent adjustment: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(5): 493– 505.

[6] Kuh, G.D., Cruce, T.M., Shoup, R., Kinzie, J. and Gonyea, R.M., 2008. Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), pp.540-563.

[7] Sandford-Ward, M. (2016). EUSA study shows need for widening participation in University societies. [online] The Student Newspaper. Available at: http://www.studentnewspaper.org/eusa-study-shows-need-for-widening-participation-in-university-societies/ [Accessed 16 Aug. 2016].

[8] White, A.M. and Gager, C.T., 2007. Idle hands and empty pockets? Youth involvement in extracurricular activities, social capital, and economic status.Youth & Society.

[9] Demos. (2015). Learning by Doing. [online] Available at: http://www.demos.co.uk/project/learning-by-doing/ [Accessed 16 Aug. 2016].

[10] Berk, L. E., & Goebel, B. L. (1987). Patterns of extracurricular participation from high school to college. American Journal of Education, 468-485.

[11] Randomisation was stratified by gender and ACORN status (coded binary as ACORN 1-3 and ACORN 4-5) to ensure even representation across the three groups.

[12] At the start of the year all students were sent an introductory message, in which they were told that they would receive messages from Kings Tips and given the opportunity to opt out. Any students who opted out were excluded from all further text trials.

[13] There were two cases in which a card was not swiped and attendance was not recorded. Signs informed students that their attendance data would be collected if they swiped their card, but that they could show their ID to a security guard if they did not want this data to be collected. In addition, students who forgot their card, or hadn’t yet collected it, could enter the Welcome Fair but their attendance was not recorded.

[14] At an aggregate level, the increase in sign-ups due to employability messages was significant at the 10% level, but not at the 5% level.

Leave a Reply