Contributed by Dr Angela Hodges and Dr Niki Hamilton-Whitaker, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IOPPN).

Their module: Brain Form and Function, BSc Neuroscience & Psychology – 70 students.

Assessment activity: students were asked to produce five graphical abstracts and choose one to submit for their final assessment. A graphical abstract is a single concise, pictorial and visual summary of the main findings of a published research article; graphical abstracts are a relatively well-established form used by large publishers of scientific journals to increase the access to and reach of scientific findings. Students gave and received peer feedback as well as receiving feedback from the tutors.

Why did you introduce this approach to assessment?

We had a new module to work with. Our students are very adept at writing essays by the end of their degree, but not necessarily as good at verbal or graphical communication. We had been thinking that asking them to consolidate science and ideas into a short narrative and a visual representation would be a good way to determine their learning. We had picked up from student feedback that they were hungry for variety, so we seized the opportunity with this new module. We designed the assessment so that students would develop their practical skills with drawing, visual software and communicating complex knowledge and concepts for different audiences.

How did you design the assessment criteria and weighting?

Graphical abstracts counted for 50% of the final mark (the other 50% was an MCQ test). There were five tasks which were progressively more challenging, but four were purely formative. We built some choice into each task – generally students had two alternatives to choose from, and at the end each student selected their best one for summative assessment.

We developed specific assessment criteria by modifying the existing essay criteria (understanding, accuracy, selection and coverage, and communication style and substance). Early on we arranged an independent review at programme level, and there were subsequent rounds of review by other colleagues outside the module.

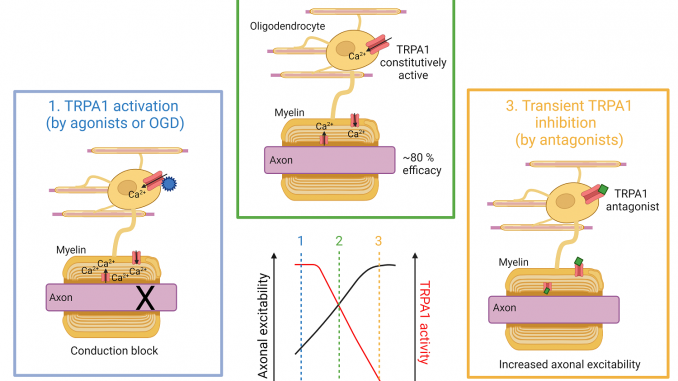

We were clear about not assessing students’ artistic skills. They would be able to choose any number of different ways to illustrate the same thing, but in the end they would need to understand that this assessment is about efficiency – focus, editing, selection, and connections – as much about what they leave out as what they select. The abstracts were composites of different images, and the positioning and the connections between them carried most of the communication – supplemented with a bare minimum of text.

What opportunities did you give for formative practice?

To familiarise students with the type of work and standards we expected, we designed some early group exercises where students analysed graphical abstracts from their peers for main findings and successful and less successful qualities, and then practised converting a written abstract into a graphical one.

We’ve mentioned that four out of the five tasks were formative and that the briefs were progressively more challenging. We also introduced students to the software fairly gently – the first task they could hand draw or use PowerPoint. By the time they got to Biorender (the best software for this, but restricted access for students) they would have already got to grips with translating ideas into visual form.

We built in plenty of feedback. There was a peer feedback tutorial for each of the five tasks. We allocated each student five other students’ work to look at and comment on verbally in the tutorial. The first two times they did this, they were also allocated one graphical abstract for more formal written peer review by the following Monday.

Additionally, for the final three tasks tutors gave individualised feedback, so that as the final assessment approached students were getting feedback from the most knowledgeable people involved in the module.

How did you introduce the assessment to students?

In the first introductory seminar we introduced graphical abstracts in depth along with our rationale for asking students to produce them. We explained why they exist, how producing them could support deeper learning, and we gave plenty of examples of graphical abstracts. We also gave some guidance on effective visual communication.

We demonstrated how to produce graphics using our suggested software. Students used PowerPoint or their hand-drawings as PDFs at first, and set up freemium accounts on Biorender. We gave guidance on graphical communication. We also went into depth about how we would assess the abstracts and introduced students to the criteria. We emphasised to students that we weren’t going to assess their drawing skills but their communication skills.

We introduced the first task in particular detail. Students were a bit nervous at the beginning, we think, and we had to clarify that the assessments were formative. But it went smoothly.

How did you give feedback?

As well as the peer feedback mentioned above there was also individual tutor feedback on the final three tasks. Students submitted via Turnitin and the work was divided evenly among five staff assessors – so for the final three tasks assessors marked 16 each. It took around 20 minutes to assess and give feedback for each abstract.

Were there any challenges, and how did you address them?

Many students struggle with summarising complex information in any form. Some of the abstracts tended to over-use text rather than using it sparingly to supplement what the images couldn’t say. Relatedly, some of the abstracts were so dense with graphics that they were highlighting trivial points to the same extent as important points, and you couldn’t see the wood for the trees. So we will be offering more support with that.

We are still working on convincing students that peer review is a good idea, and guiding them to give high quality feedback. They value tutor feedback but are a bit sceptical about peer feedback – and even GTA feedback. Sometimes they didn’t show up to give peer feedback to their partner, and occasionally they didn’t seem to be acting on it. We’re going to use research evidence to persuade students of the value of peer feedback, and to raise their confidence that they are competent to do this – and in fact, this is something that you need to do in your life. Additionally we need support and access rights for the peer feedback activity on KEATS (Moodle Workshop) because it is quite complicated to set up the first time.

Students did raise workload issues with us, and on reflection we agreed that five abstracts was a lot to ask them to balance with their assessments on other modules, so we have reduced this down to four in subsequent years. We also would like to know more about whether the time we estimated it would take students was correct.

Since there were several assessors, we needed equivalence of quality and amount of feedback, otherwise students would notice the inconsistency. So in Turnitin we agreed to use the rubric, some embedded comments, and summary comments of five good points and five points that could be improved.

We wanted students to have the chance to use particular software called Biorender since it’s the best there is for this kind of thing. It has an image bank where each image is modular and can be taken apart and adapted, so students don’t need drawing skills to make a professional-looking abstract, and they can do it in far less time than on, say, PowerPoint. Unfortunately despite demand we don’t have a site licence for it – fortunately though students could make two images for free which meant that they could use it to create their more advanced abstracts.

What benefits did you see?

The quality of the abstracts exceeded our expectations, and students’ submissions for the final assessment were fantastic. Most students valued the refreshing change from normal assessment, and we think it helped their learning stick. Students’ engagement with the formative assessments was higher too.

Some quotes from students in their module evaluations:

“The most positive aspect was the creative way of testing and assessing what we have learnt through graphical abstracts.”

“Learning how to do a graphical abstract was definitely intellectually stimulating.”

It was easy for us to assess students’ learning. The images worked as well as vocabulary in written essays, and the graphics students made with them showed how they were connecting them. Additionally, we enjoyed marking much more. In total, we each marked 80 separate abstracts – it was far more interesting than if we had had to mark 80 essays (which anyway wouldn’t have been feasible in the time we had). In the final assessment we came up with the same marks independently – we were almost bang on. That had been one of our concerns with this new assessment approach, but it was brilliant. We think it’s because we had been on a journey together coming up with the criteria and assessing the five tasks.

Do you have any advice for colleagues who are considering trying this?

It’s important that the visual abstracts are relevant to the concepts and knowledge students are learning, and that they are integrated. It’s also important that they aren’t a one-off, because students need time and opportunities to develop their skills. Despite what may seem like a big staff workload, you can expect the work to lessen over the course of the term. We definitely find this approach rewarding and beneficial for students.

Anticipate that students will need quite a lot of learning support to understand what graphical abstracts are and why they exist. Where students have succeeded with their essays in the past, they can tend to put too much effort into text explanation, so it’s important to emphasise early and often that it’s the graphics which need to be doing the talking.

Keep students’ workload in mind. We had anticipated each task would take one or two hours, including reading the article. After student feedback we adjusted the timings to set four tasks with deadlines at three-week intervals. Anticipate an assessor workload too – around 20 minutes per abstract, to assess and give feedback.

We have briefs we can share with anyone who would like to try it.

Leave a Reply