Caroline Norrie and Nicole Steils are researchers at the Social Care Workforce Research Unit (SCWRU), King’s College London. (618 words)

The identity of Approved Mental Health Professionals (AMHPs) was the subject of a joint SCWRU and Making Research Count seminar held on Thursday, 23 August 2018, at King’s College London (KCL) as part of the Contemporary Issues in Mental Health series.

Dr Caroline Leah

The presenter, Dr Caroline Leah, Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Health, Psychology and Social Care at Manchester Metropolitan University, discussed findings from her recently completed PhD about the role and identity of AMHPs, as well as enabling the audience, many being practising AMHPs, the chance to participate in lively discussions throughout the seminar.

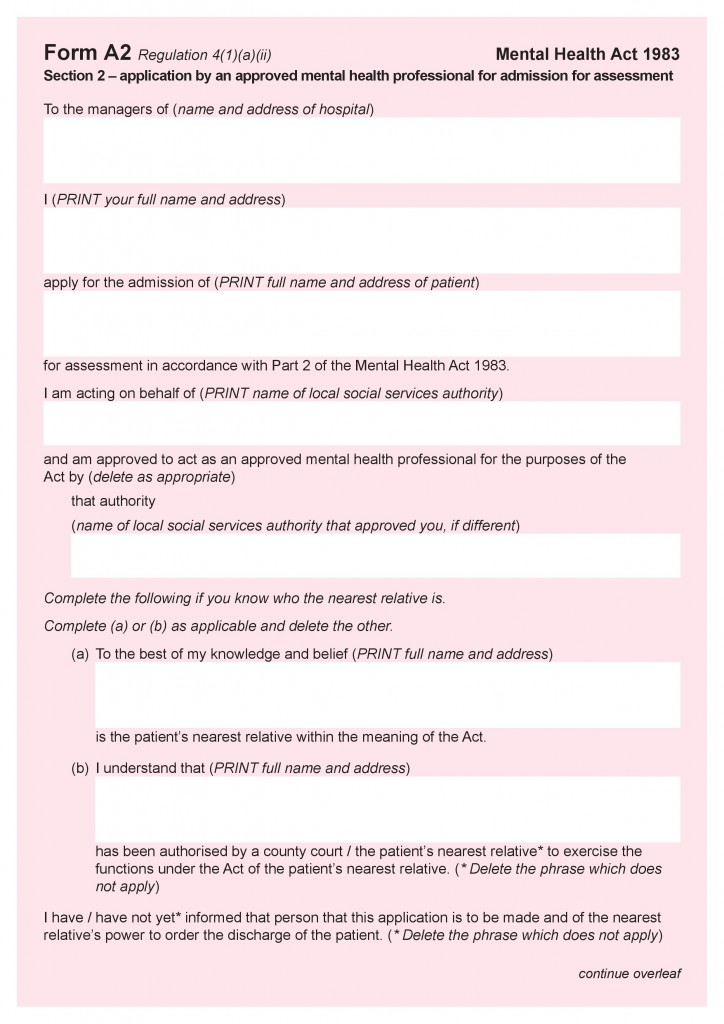

An AMHP is a professional who is authorised to make certain legal decisions and applications under the Mental Health Act 1983; their powers include sectioning service users. This professional will usually be a social worker, who has undertaken additional training. In 2007, however, the law was amended to allow other mental health professionals to train for and to undertake this role. It is therefore now possible for psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists or psychologists to qualify as AMHPs, although this is still unusual. Continue reading