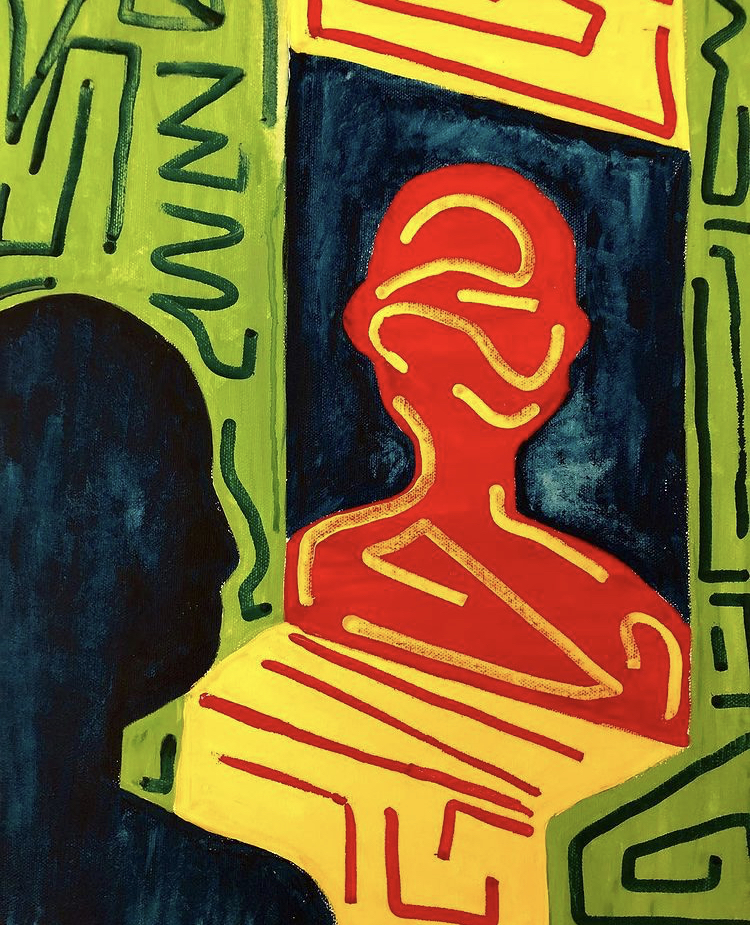

Words: Penny Newell // Paintings: Amber Smyth

During the pandemic I was diagnosed with a condition called adenomyosis. I am a gender-nonconforming lesbian who suffers with debilitating period pain.

Early periods in my teenage years were always strangely painful. It was a pain that I saw but did not want to see as my own. I remember spending a lot of time lying on the floor at home with feet lightly treading around me, my people going about their reassuring business.

My periods recently got really bad. I faint. I struggle to eat or walk. I usually spend 2-3 days in bed. You will often find me in a hot bath at 3am with a wet towel held to my stomach. It’s a dynamic condition. I feel okay. I feel great. I feel abundant. Yet when I feel strong, healthy, here, I have borrowed these feelings from someone else. Being okay is on loan to me.

Adeno pain is like endometriosis pain – cyclical, chronic and acute, medically dismissed, feminised, difficult to describe. The pain is usually coupled with a lengthy diagnosis and lack of acknowledgement.

Since this started, I have desperately sought out some form of queer solidarity. Initially, I was working in Waterstones selling hundreds of hard copies of Emma Barnett’s It’s About Bloody Time. Period (2019). This followed an article from Cara Jones in 2016, where she spoke about endo pain as feminised and sexualised. Most of the stuff out there continues to follow Barnett’s model of depicting endo pain as an overlooked women’s problem. ‘Women’s health’ continues to be how mainstream journalism frames the condition. In an article published in 2018, Przybylo and Fahs attempted to speak about all dysmenorrhea (the medical term for period pain) as a crip experience. They refer to sufferers as ‘menstruators’ rather than ‘women’. They do so to ask how menstrual pain could become central to new kinds of solidarity, ‘based on alternate temporalities, cyclical experiences of time and performance’ (223).

I could not agree more that we need to deepen our solidarity around menstrual pain and strive for queer crip social time and performance. It is estimated that people with endo / adeno pain lose around 10 hours of productivity a week. If that sounds like a capitalist formula, it is! Because here we are, living in a capitalist world where cyclical pain = bad performance at work = sacrificing social time to meet unrelenting demands of waged relations = cumulative pressure across the month, year, career. With hope, an active and flexible support network takes a share of this burden of time; they return it as time you can give to relief.

Solidarity can be foundational to imagining time away from these constrictions, to performing in the otherwise. Yet before we build solidarity around dysmenorrhea, we need to vastly complicate how we see menstrual pain as a disability (if that is indeed a necessary step). We need to ask who remains centred in this proposed solidarity circle?

Thinking about all of this made me return to Jasbir Puar’s ‘triangulation’ of the disability/ability binary with “debility” in The Right to Maim (2017). The understanding of all dysmenorrhea as disability hides the way that feminisation can be capacitating. For ciswomen chronic period pain can be seen, care can be received, and adjustments can be made. Non-transgender adeno and endo women have capacities that are withdrawn for non-binary and trans people suffering with dysmenorrhea or related experiences of pain. Trans men, trans women, transmasculine people, and transfeminine people are all capable of experiencing period pain. Yet these people are not determined as capable of this chronic and cyclical pain within the feminised regimes of menstrual disability (again, see Pryzbylo and Fahs for more on this, or see Jones’s much more recent article where she argues that people with endo need to openly claim disability.)

Passing as a cishetwoman or as homonormative presents strong opportunities for solidarity within the healthcare system, in the workplace, and in social groups. In an early consultation, a specialist stepped outside her formal chit-chat with me to recommend having a baby as a treatment. In a recent phone consultation, a GP told me that her daughter ‘swears by her moon cup for her period pain.’ Sufferers are supposed to buy into these identifications, these moments of professional collapse. Such vacations performatively invoke some prior state that I am supposed to seek to get to, beyond this queer pain. Acts of solidarity shore up adeno gender performance, compelling this body further and further, further and further away from me. With disgust, I repeatedly sense and resist such opportunities to perform as more-woman-than-me, to heal pain by closing queerness down.

In my limited experience, formal medical treatments leave little scope for gender queerness and queer sexualities because most are borrowed from birth control methods articulated towards heteronormative reproduction. I repeatedly tell the GP that I am a lesbian and that hormones have been recommended to me as a treatment for a disease, not as a contraceptive. These exhaustions of misgendering and anti-queerness are shared across the queer spectrum of adeno and post-adeno experiences. In a decisive moment of desperation, I wrote a letter to the GP to ask them to re-write a consent form for one such treatment, so that I could sign it. They held a practice meeting to discuss the language that they use.

(This should make apparent how dysmenorrhea-as-disability is equally determined by health literacy, class, race – my GP no doubt responded amicably as they saw me as not just a woman but a middle-class white woman, in fact, I was later made aware that they mistook my title of ‘Dr.’ as implying I am a clinician, so a white woman clinical professional – economic empowerment, nationality, and language proficiency, to name just a few productive differentials in adeno and endo gender performance.)

Invisibilising adeno and endo pain is not misogynistic. Centring adeno and endo pain as ‘women’s pain’ doesn’t make this pain any more real. Rather, this trans-erasive feminisation of adeno and endo pain forecloses the possibility for queer crip solidarity and performance. This trans-erasive feminisation is a debilitating refusal to see queer dysmenorrhea.* In the GP practice, on care leaflets explaining procedures, in phone consultations, chats with colleagues, passing discussions with well-meaning friends, queer dysmenorrhea is refused. As in: it’s time for you to go home now. Leave your body at the door. Meaning: do not bring your queer trouble here again.

I sit at my computer feeling okay and wonder how I give this time. I contemplate the accidentally doubled-doubling whereby I somehow own two second-hand copies of José Esteban Muñoz’s books. What hope does the futurity of pain resolve itself in? I give time to the queer troubles of this question. Time that is better spent otherwise I imagine, I use it to imagine the not-yet of queer solidarity. I occupy this time. I offer this time. It is a ground.

Anna Daučíková:

6

Triangulation – labouring in inklings … surveying what does not exist yet.

(One needs to take care for the quasi-skill of touching up what would become.)

*On attending A&E on one occasion I was told in these exact words: “the gynaecologist is refusing to see you.” This was later explained to me as a “miscommunication” between A&E and Gynaecology. I experience this as the literal expression of the figurative existence of so many queer people within endo and adeno cultural narratives.

Penny Newell is a Lecturer in Theatre and Performance Studies (AEP) at King’s College London, working across queer ecologies and gender studies, disability studies, the history of philosophy at its intersection with performance theory, performance art and practice-based methods, and critical theories of race and the ecological (in)humanities. Penny is currently writing and making collaborative work about ‘maintenance’ as a persistent theme in critical thought, performance practice, and environmental technologies.

Amber Smyth (she/they) is a second year Liberal Arts History major at Kings College London working as an actor/ agent with a cooperative agency alongside their studies. Focussing academically on Queer and Feminist histories, much of their artwork encompasses questions of expression of gender identity and binary systems that both restrict and inform queer experience.

Instagram: @cheapcanvases