Adam Shepherd is a third year medical student at King’s College London. For Trans Day of Visibility he shares his reflections as a trans man researching transgender people’s experiences in healthcare settings.

When I was born, a doctor assigned me to be “female”. During my childhood I felt increasingly at odds with the ways that I was being socialised as a girl by the world at large, but it was only in my early twenties that I learned a word to make sense of my growing unease: Transgender.

As a Latin prefix ‘trans’ simply means “on the other side of”. Nowadays ‘trans’ epitomises much more than that – it is an umbrella term for diverse identities and experiences of people whose gender does not align with the one they were designated at birth. To me, ‘transgender’ encapsulates that feeling of comfort, pleasure, and relief of arriving after a long and tiring journey: home sweet home.

However these definitions are a far cry from how we were understood even 70 years ago. From labelling trans people as mentally ill and promoting the use of psychotherapy to cure us, to realising the benefits of letting us transition to our identified gender, the relationship between medicine and the trans community has historically been strained.

The impacts of this is still felt today. A 2016 report found that transgender people in the UK, on average, experience higher health inequalities than cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. In 2018, Stonewall and the National LGBT Survey showed how trans individuals are more likely to face discrimination in medical settings, and more likely to avoid seeking healthcare when they need it.

As an aspiring doctor I was appalled at the anecdotes I heard in my own support groups – stories of being met with ignorance and insensitivity when seeking medical care as a trans person. My first opportunity to do something about this came when I undertook my Masters of Public Health dissertation in which I explored trans people’s experiences of primary care.

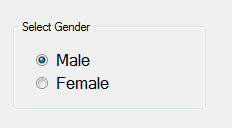

In my research, communication emerged as a key factor shaping the relationships transgender people had with their General Practitioners. Yet even before entering the consultation room, participants had to mediate inflexible medical records which failed to recognise their identities and bodies. Fixed ways of thinking about gender are embedded in healthcare practices through these processes and documents, making communication only part of the problem.

To make sense of this, sociologist Ruth Pearce proposed two conceptual models to think about the experience of being trans. “Trans as condition” depicts the traditional understanding that ‘trans’ can be clearly defined, often by a healthcare professional, and that transitioning resolves a person’s transness. “Trans as movement”, in contrast, posits that ‘trans’ is variable and versatile, similar to how we subjectively experience the world around us. From this viewpoint, ‘trans’ stops being a defect that needs correcting, and becomes a social identity.

Working with Dr Benjamin Hanckel, I sought to better understand how the changing conceptualisations of trans experiences were reflected in healthcare guidance, and whether it aligned with lived experiences of transitioning. Looking at healthcare guidance documents by NHS England illuminated these discrepancies. Changes over time in the language used illustrate how institutional shifts towards the idea of “trans as movement” has enabled greater numbers of gender diverse people to emerge from the shadows through being officially recognised in these documents. However, rigid medical forms often do not account for diverse experiences of gender. Consequently people who are transitioning continue not to be accounted for in health structures built around the expectation of cisgender bodies.

What is evident is that for healthcare to become inclusive of all trans people, we need to tackle the very design of healthcare organisations, which is often based on outdated ideas of gender. But gender is a complex topic.

In another project Dr Benjamin Hanckel and I asked young people who visited the Science Gallery London exhibition GENDERS: Shaping and Breaking the Binary to explore what gender meant to them. Whilst traditional ideas of gender surfaced, early findings point to how many young people are increasingly open about gender, recognising it as being fluid, even if at times it feels restrictive, reminiscent of a “trans as movement” framework. Nonetheless, the question remains as to how these new and shifting models of gender, that recognise everyone’s myriad and diverse experiences, will enter into healthcare provision.

As I look towards the future of becoming a medical professional, I realise there is a way to go until transgender people are not just accepted, but have their needs acknowledged in healthcare settings. With the recent court case concerning the provision of puberty blockers to trans youth and continued lack of knowledge among healthcare providers, the future might seem bleak, but change is on its way. From Brighton and Sussex NHS Trust expanding vocabulary for midwives to include gender neutral terms, to the emergence of new grassroot organisations to advocate for the health needs of the trans community, the tide is slowly beginning to turn.

Further Reading: