Jessie Krish, who recently joined Equality Diversity & Inclusion as a part-time Project Assistant, and works outside of King’s as an independent curator, shares her reflections on the Black Lives Matters protests of the summer and how they inform work in the Cultural Industries and Higher Education sector. She recently co-edited a ‘Reader’ for e-flux journal on Loot and Looting.

After Minneapolis Police officers killed George Floyd, protests grew, and cities around the United States saw their buildings boarded with sheets of plywood: a defense against the threat of looting. With workers who usually inhabit these buildings absent due to Covid-19 lockdowns, the boards were there to protect commodities. Donald Trump’s command “when the looting starts, the shooting starts,” was a violent call to protect property, even at the expense of human life.

Whilst it is crucial to maintain the distinction between political protest and particular instances of looting that occurred in the recent wave of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests, it was looting in particular that escalated the protests, polarised public and political opinion, and contributed to the explosive impact of the BLM movement. Some viewed these acts of theft and vandalism as symbolic rejections of structures perpetuating state violence, systemic racism, and capitalist exploitation. But mainstream coverage in the United States’ media tied looting to people of color, and failed to connect these actions with the histories of systematic dispossession that Black Lives Matters activists protested, or the racialised extraction that subtends economic activity almost everywhere.

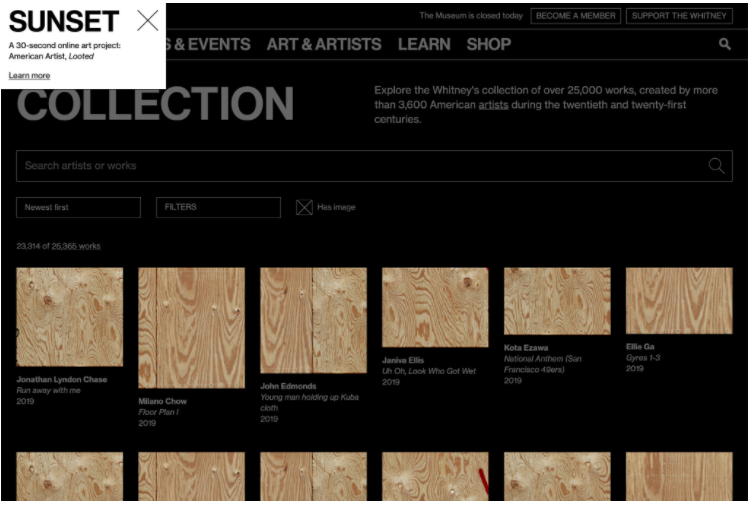

In the midst of the protests, American Artist presented an intervention at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s online collection, in which all digital images of the museum’s artworks were temporarily replaced with a plywood texture. The title of this project, Looted, pointed directly to the imperial legacies and colonialist practices of many Western museums, as well as activist and artistic institutional critiques in which the uncomfortable figure of museum “loot”, stolen from indigenous peoples and foreign nations and yet to be repatriated, is often central.

Presenting Looted as an act of ‘redaction and refusal,’ the Whitney sought solidarity with activists, and to reframe the narrative around the boarding up of the museum’s building during this period. American Artist’s Looted highlights the extreme contradictions that cultural institutions must hold (for example, guarding looted national property, whilst developing convincing and inclusive postcolonial narratives) when they engage with decolonial work. Work which requires structural, material and cultural change.

The boarded museum and its website populated with squares of rendered plywood, is a visual reminder of the close proximity of current state violence to the museum’s stolen imperial acquisitions. Whilst they can feel worlds apart, the street, museum, and university are at close quarters, and activities in each domain stand to impact cultures, structures, and material outcomes across the board.

I’m writing following the recent publication of Universities UK’s report Tackling Racial Harassment in Higher Education (November 2020). Following the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s publication of evidence of widespread racial harassment on university campuses just over a year ago, this report calls on university leaders to acknowledge that UK higher education perpetuates institutional racism. It cites ‘racial harassment, a lack of diversity among senior leaders, the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic student attainment gap and ethnicity pay gaps among staff as evidence’. Recognising that racial harassment is just one dimension of structural racism in the Higher Education sector, it acknowledges the depth of this problem and the breadth of work required, making detailed and evidence-based recommendations beyond the scope of the guidance, including the need to diversify predominantly Eurocentric and white university curricula.

Reflecting on a year in which the BLM movement has exploded and been met with the force of the state, racial discrimination has risen, and racial health inequalities have been exposed as a matter of life or death with grossly uneven outcomes for coronavirus patients of different ethnicities, I am heartened to see UK Universities addressing harassment so thoroughly. I share their positivity for the impact that the HE sector could have, with the potential to shape the minds and attitudes of 429,000 staff, and 2.3 million students, a generation whom, particularly in London, will be unprecedented in their diversity. Time to get to work!