Alex Prestage is Equality, Diversity & Inclusion Manager at King’s. Throughout his career, he’s reflected on resilience in Higher Education and now offers his thoughts on its potential as the King’s community rise to challenges posed by the current pandemic.

Resilience – a word we often use in times of crisis.

Before continuing to read, spend a second or two to reflect: what is resilience? Where does it come from? How can it be measured?

What were your thoughts and reflections? Was it an easy concept to define? Do you think you have it? How much do you think you have? When will you know you have enough? How do you get more?

Of course, I’m being only slightly facetious here. Resilience is a word we rarely define in specific terms and it’s almost impossible to measure quantitatively – the threshold for it is usually imagined. It’s a hard concept to grapple with, and often just leaves us wanting more.

Resilience is commonly defined as the capacity for an individual or organisation to recover from adversity – something, perhaps, we can all relate to of late; something we are going to, collectively, need more of in the future.

However, the UK Education sector (not just HE) and successive governments have a worrying habit when speaking about resilience – a habit of adopting a flawed model and way of thinking, particularly when referring to our learners and their outcomes. You might remember Nicki Morgan and David Cameron’s Character Education or be familiar with Angela Lee Duckworth’s grit.

Typically, when invoking ‘character’ or ‘grit’ we refer to resilience as essential or innate; something that people either have some (or no) capacity for and that this is static. More often than not, we refer to a deficit of resilience, a lack, suggesting that the outcome of a situation may have been more positive “if only X had been more resilient”.

It’s this conceptualisation of resilience in HE that I and others have written about before, and this understanding that I think UK HE, and King’s, should move away from if we are to be truly resilient to the adversity we currently face and will continue to face as a community of colleagues and learners. However, I’m not about to bash an idea without an alternative to propose.

So, what am I suggesting?

Reconceptualising resilience.

Naturally as an Equality, Diversity & Inclusion Practitioner (and lapsed social scientist), I draw from minority voices – those who have the most adversity to – for sage guidance and advice.

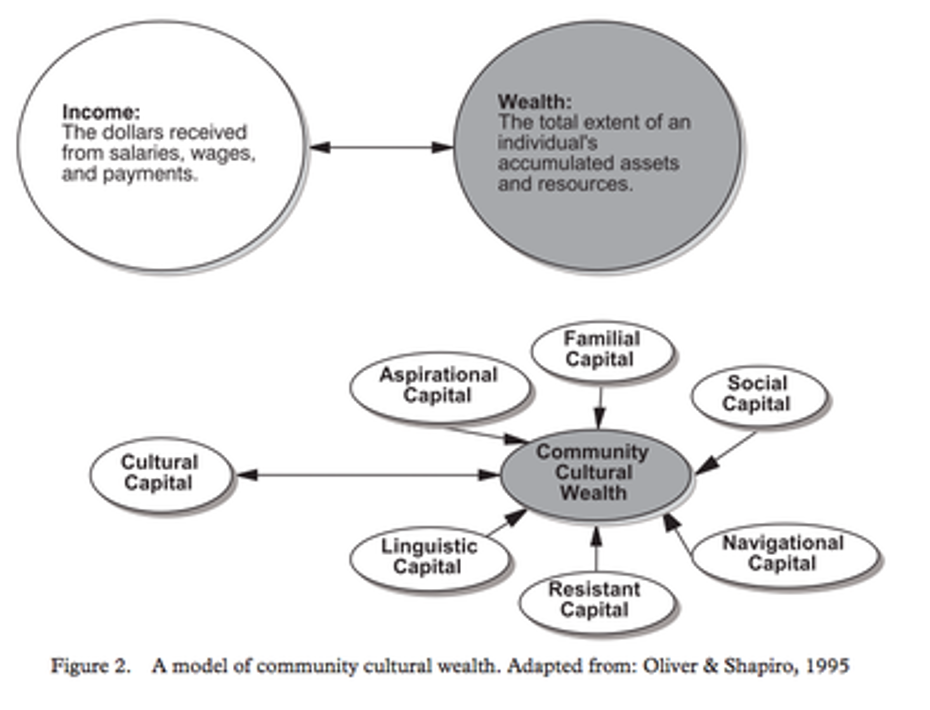

Professor Tara J. Yosso, a critical race theorist who applies CRT to education and access, explores the subject of community cultural wealth to recognise the diverse, often ‘invisible’ forms of wealth and capital ethnic minority communities have access to (or don’t).

Professor Jaqueline Stevenson applied Yosso’s model to students studying in UK HE, and used the framework to better understand what makes communities and individuals resilient (or not).

Professor Jaqueline Stevenson applied Yosso’s model to students studying in UK HE, and used the framework to better understand what makes communities and individuals resilient (or not).

The research of both academics suggests that resilience is in fact a social phenomenon. Rather than being intrinsic to the individual, resilience is generated and created by communities; and, by extension, we all play a part in developing and maintaining others’ – and our collective – resilience. Like a big team effort, if you like. It’s also important to recognise that many of the factors influencing resilience are beyond our control – empathy walks are a great way of visualising and demonstrating this fact.

In the context of a global pandemic, and the challenges we as a community of colleagues and learners face and will continue to face, I’d like to focus on three forms of capital we can all help foster:

- Aspirational capital, our ability to maintain hopes and dreams;

- Social capital, our network links and community resources including emotional support;

- Navigational capital, our ability to maneuver through institutions.

Indeed, I’ve spotted examples of our community adapting and fostering these assets in our emerging response to the situation, but I’d like to emphasise the value in the subtle, ‘soft’ behaviours – they aren’t just for lockdown, but for life!

Aspirational capital — with so much ambiguity and uncertainty, it can be hard to maintain confidence in our hopes and dreams. We might need some time to take stock and (re)appraise our goals in light of the new parameters and context we find ourselves in. For many of our students, particularly finalists, this will be an area of vulnerability and concern. It’s important to recognise the emotional toll that this sense of loss, ambiguity, and a process of reimagining our hopes and dreams might take; each of us can be alert to this fact and seek to support one another with finding new hopes and dreams, no matter the scale.

Social capital – whilst the everyday reality of lockdown looks different for everyone, varying according to our caring responsibilities, living situation, health etc., we all have a degree of social distance and isolation between us. It’s been fantastic to see many of the teams I work with across the university initiating digital coffee breaks to maintain the social fabric of King’s. Our networks and connections are assets we draw on in our work and learning, especially in the face of adversity. Creating and developing opportunities for staff and students to e-meet, connect and enjoy the benefit of a simple conversation is more important now than ever before.

Navigational capital – as our context changes, we’ve rapidly adapted our teaching and services, impressively so! . For some of our students and staff, this will mean trying a new platform (like Zoom or MS Teams) or will mean that they are required to navigate another part of our already complex organisation. Where we have been required to change and adapt, it’s important to bring others with us, providing clear instructions and signposting as applicable. Something that might seem glaringly obvious from one perspective might not be the case from another.

They may seem like small steps, nudges if you like, but theory (and my own practice) suggests that we will foster a more empathetic, more resilient community through renegotiating and so maintaining hopes and dreams, taking time with one another socially, and providing clear instructions with no assumptions. I’m passionate about realising a reality where we take collective responsibility for addressing and weathering the adversity we face — a community of colleagues and learners where we are stronger together than apart.