Every October Black History Month is marked across the UK.

This year’s theme for Black History Month is “Time for Change: Action not Words” and we’re committed to ensuring our celebrations at King’s College London inspire and support tangible action.

Throughout the month we will be sharing Black History research and achievements of our Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic alumni, as well as hosting various events (details below) across the university. At King’s we are committed to creating an anti-racist university and working on initiatives that go beyond the month of October. Later this month we’ll be sharing more on our new race allyship toolkit and race equality maturity model which is currently in development.

To help you get involved with Black History Month at King’s we have pulled together some interesting reads, useful resources and a spotlight on some of our upcoming events in this blog.

Must Reads

- Want to hear a story? Nine recommended books to read for Black History Month. Final year BSc Children’s Nursing student and Student Knowledge and Content intern, Rianna John has written an article in celebration of Black History Month. Rianna shares a list of 9 brilliant books written by Black authors.

- Black History Research and Teaching at King’s. To celebrate Black History Month 2022 we take a look at some of the research and teaching on Black History going on at King’s. If you are researching or teaching about Black History please get in touch so we can raise awareness of your work throughout this month and beyond.

- The IoPPN Race Equality Network invite you on a journey of self-directed learning. The team have created this really useful Black History Month Padlet, bursting with resources, quick reads and ways of getting involved.

- Dyslexia & Me. Onyinye Udokporo, 2020 alumna of the Education, Policy & Society MA, published her first book in September 2022, retracing her journey in academia as a Black woman with dyslexia and offering tips to students on how they can also make the most of their time at university. You can find out more about the book on our KCL news pages here and you can hear more from Onyinye in her blog ‘A book, a business, and a Master’s degree: just the start of the journey’ here.

Useful Resources

- You can keep track of what is happening at King’s throughout the month by visiting our staff intranet page here.

- For students you can keep up to speed with everything happening this month by visiting our student news page here and checking out the KCLSU Black History Month event pages here.

- Don’t forget to visit the Black History Month Website here, which is full of news and events taking place across the country.

- Follow out team on twitter (@KCLdiversity), we’ll be sharing content throughout the month.

Event Spotlight

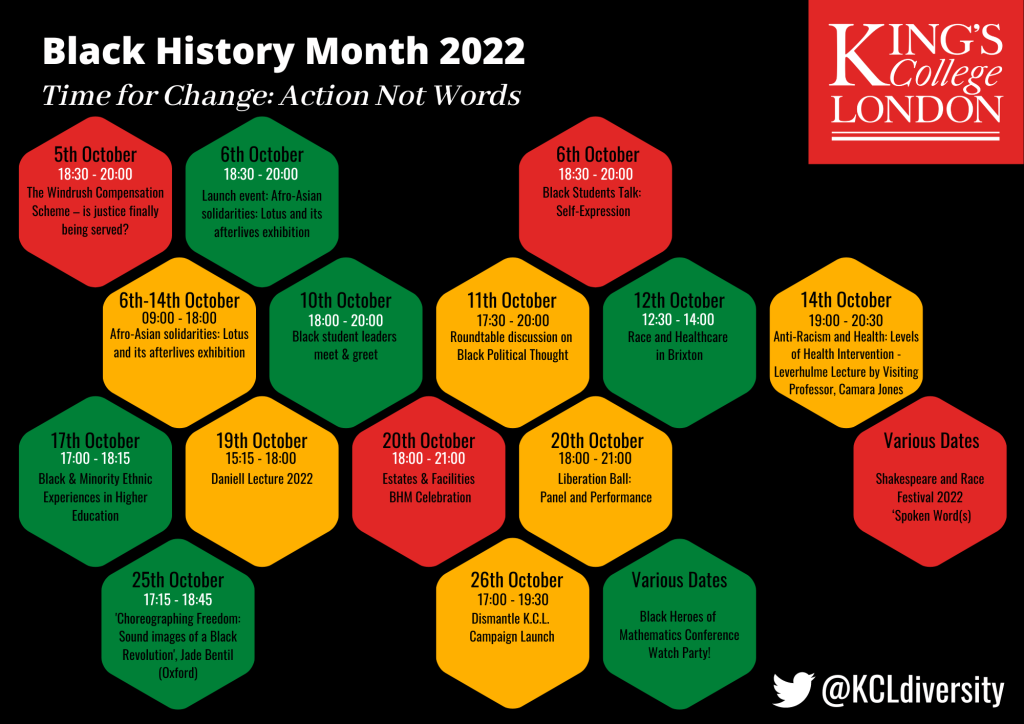

Click image to expand the calendar of events

Events taking place across the university this month include:

Afro-Asian solidarities: Lotus and its afterlives exhibition

Thursday 6 October 2022 to Friday 14 October

The exhibition aims at fostering inclusive pedagogy through a focus on the anti-colonial writers and artists of the Afro-Asian Writers Association and their journal Lotus published in Arabic, English and French from Cairo and Beirut (1960s-1980s).

Building on our interdisciplinary expertise we foreground the importance of this neglected body of cultural production from the Global South, stressing its centrality in the making of contemporary global politics and world literature.

Shakespeare and Race Festival 2022

The theme of the Shakespeare and Race Festival 2022 is ‘Spoken Word(s)’, withevents and resources available through out the month.

The festival will also showcase new and exciting creative work from the Folger Institute, as well as ground-breaking research from Shakespeare and Race scholars from around the world. This year, the Festival is co-produced and co-sponsored by King’s.

Black Heroes of Mathematics Conference Watch Party!

We are warmly inviting you to “Black Heroes of Mathematics Conference Watch Party!” We have dedicated rooms to watch this year’s conference, organised by LMS. Details on the event can be found here: https://www.lms.ac.uk/events/black-heroes-mathematics Please check below when and where you can watch the talks at KCL: Schedule:

– 4/10/22 13:00-16:30 Talks broadcast at Room: FWB 1.20 (Waterloo Campus).

– 5/10/22 10:00-12:00 Talks broadcast at Room: S-1.08 (Strand Building).

– 5/10/22 12:00-13:00 Lunch will be offered at Room: K2.29 (King’s building).

– 5/10/22 13:00-15:30 Talks broadcast at Room: K0.19 (King’s building).

The rooms have specific capacity so the attendance will be monitored at first come first serve base.

Events calendar:

The Windrush Compensation Scheme – is justice finally being served?

Wednesday 5 October, 18.30 – 20.00

Set up to right the wrongs committed against the victims of the Windrush Scandal, the Windrush Compensation Scheme ( WCS ) has been in operation for over 3 years. The WCS has been subject to significant criticism which has led to some reform. The panel will provide a current assessment of the WCS and whether it is finally delivering justice.

Launch event: Afro-Asian solidarities: Lotus and its afterlives exhibition

Thursday 6 October, 18.30 – 20.00

The exhibition aims at fostering inclusive pedagogy through a focus on the anti-colonial writers and artists of the Afro-Asian Writers Association and their journal Lotus published in Arabic, English and French from Cairo and Beirut (1960s-1980s). Building on our interdisciplinary expertise we foreground the importance of this neglected body of cultural production from the Global South, stressing its centrality in the making of contemporary global politics and world literature.

Black Students Talk: Self-Expression

Thursday 6 October, 18.30 – 20.30

Black Students Talk (BST) is a peer support group that provides safe, supportive and therapeutic spaces for students at King’s who identify as Black (African, Caribbean, Mixed with Black heritage) to meet, share, learn and manage their mental health and wellbeing. These sessions are run by students, for students!

On Thursday 6 October, BST will be kicking off for the new academic year with a Black History Month session on Self-expression. Come along to Guy’s Hodgkin Building Classroom 11 for a thoughtful discussion in a warm and welcoming environment.

Find out more about BST on the KCLSU website

Black Student Leaders Meet and Greet

Monday 10 October, 18.00 – 20.00

Join us in the Vault to meet others in the King’s Black students community and say hello to some of our Black Student Leaders heading up our societies, networks and rep roles. Discover their plans and campaigns for the year to come as well as finding out more about plans for Black History Month!

Roundtable discussion on Black Political Thought

Tuesday 11 October, 17:00 – 20:00

What is the history of Black political thought – as a subject, as a disciplinary field? What should it be ? How should historians and other scholars think of it now? Join the KCL History Department and the Medicine and the Making of Race Project for an evening discussing these and other questions with an all star panel of experts in the field, including:

– Dr Tonya Haynes, University of the West Indies.

– Professor Tommy Curry, Edinburgh

– Dr Kesewa John, UCL

– Dr Dalitso Ruwe, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON

– Dr Meleisa Ono-George, Oxford

– Chair: Professor Richard Drayton, KCL

Race and Healthcare in Brixton

Wednesday 12 October, 12:30 – 14:00

Joining us for a discussion about healthcare, race and activism in Brixton, Paul Addae, from the Brixton community organisation Centric, and colleagues open the floor up to history students and interested others to learn about both the long history of activism in Brixton and the legacy that that history has had for the current, dynamic activist agenda around healthcare.

In a conversation that takes us from the limitations of healthcare now to the history of an activist community to the history and contemporary of race and racism in our country now, this discussion with the ‘off stage historians’ of Brixton offers the opportunity to delve into critical contemporary issues as these are refracted through the lens of healthcare.

Black & Minority Ethnic Experiences in Higher Education

Monday 17 October, 17:00 – 18:15

King’s Equality, Diversity and Inclusion team invite you to join Professor Kalwant Bhopal and Professor ‘Funmi Olonisakin talk about the experiences of Black and Minority Ethnic people in higher education.

This event has been designed to reflect this year’s Black History Month theme (Time for Change: Action not Words) and audience participation is encouraged. It is free to attend but space is limited so please book your place. If you have any access requirements then please contact diversity@kcl.ac.uk

Engaging with Blackness – a showcase of some current CMCI research

Monday October 17, 16:30pm – 18:00

Kings Building, K-1.56

This event is intended to introduce you all to some of the current research happening in the CMCI department, that in some way engages with Blackness. In addition to finding out more about the department’s research activity, this event encourages us all to think more reflectively about ourselves as academic researchers. Each of the speakers will provide a short presentation, followed by a conversation (including audience questions) that will be moderated by Dr Jonathan Ward. There is no need to register for this event.

Liberation Ball: Panel and Performance

*UPDATE – Postponed to February 2023*

Join us for our very own Liberation Ball, a homage to London’s queer ballroom scene. This event will be a celebration of achieving liberation through art. We will begin with an informative and exciting panel of London ballroom icons, exploring the history of ballroom culture and its significance to the black, queer, and trans communities. Followed by a ball itself where students will have the opportunity to walk in three categories (Runway, Best Dressed and Vogue) and showcase their talent.

Find out more and register here

Meet Juliana Oladuti, the Author of ‘Queen’ for a reading + Q&A, followed by a social

Tuesday 18 October, 13:30-15:30

Activity Room D (Bush House South East Wing, 300 StrandvWC2R 1AE

Join us in celebrating Black History Month with the launch of a fantastic new book “Queen” presented by the author, Juliana Oladuti, on the day. We’ll have a reading & Q&A followed by a social.

Book Synposis: From a tradition of oral storytelling, Juliana, a Nigerian in her seventh decade, decided to challenge herself by putting pen to paper and writing the story of Queen. A bright village child who, despite being born into a culture and at a time when girls were not valued, Queen is forced to undertake an odyssey. The journey takes her through West and North Africa and eventually to Europe.

Wednesday 19 October, 15:15 – 18:00

PhD student Desmond Koomson will talk about his journey into chemistry research and his current and previous research ahead of the Daniell Speaker guest speaker (Professor Sir David Klenerman FMedSci FRS, Department of Chemistry at the University of Cambridge).

Estates & Facilities Black History Month Celebration

Thursday 20 October, 11.00 – 13.30

The E&F EDI Race Equality Workstream are holding an event to celebrate Black History Month. This would be an opportunity to celebrate our colleagues success across E&F and discuss remaining challenges.

Choreographing Freedom: Sound Images of a Black Revolution

Tuesday 25 October, 17.15 – 18.45

In late twentieth-century Britain, Black women, queer folks and transfeminine people were crafting new ways of living. Situated in the heart of Empire, outlaw women, erotic dreamers and gender rebels refused to adhere to the prevailing norms and codes that organised their lives. These adventures with beauty, sex, pleasure and performance offered blueprints for imagining a radically different world.

In a series of extracts from Bentil’s forthcoming book, Rebel Citizen, she explores the lives of those whose stories resist the dominant narrative of History and the insurgent desires that shaped the everyday revolution of Black life in 1970s and 1980s London.

Film screening and conversation with filmmaker Carl Earl-Ocran

Tuesday 25 October. 18:00 – 20:00

This event will comprise of a screening of the short films ARACHNID and HACKNEY DOWNS (both written and directed by Carl Earl-Ocran.) This will be followed by a drinks reception and conversation and audience Q&A, moderated by Dr Jonathan Ward (CMCI). This event will be live-captioned throughout.

Carl is a British-Ghanaian writer and director, with a passion for storytelling. His aim is to tell long form narratives with personal yet universal themes, sharing emotive, character-driven, socially conscious stories with compelling high concepts, highlighting, in particular, underrepresented voices.

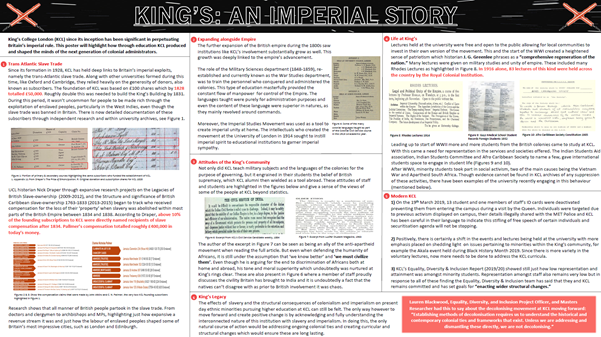

Dismantle King’s Colonial Legacy Campaign Launch

Wednesday 26 October. 17.00 – 21.30

This is the launch event for a student and staff led campaign to Dismantle King’s Colonial Legacy. This event is open to all interested students and staff, and will feature a variety of talks from activists and academics, group discussions and performances.

Anti-Racism and Health: Levels of Health Intervention – Leverhulme Lecture by Visiting Professor, Camara Jones

*UPDATED DATE*

Monday14 November, 19.00 – 20.30

In this, the first in a series of three public lectures on Anti-Racism and Health to be offered by Professor Camara Jones during the year, she will make the case that “racial” health disparities cannot be eliminated until racism is named and addressed. Engaging with audience members in a spirited conversation exploring the pertinence of these ideas in the United States and United Kingdom contexts.

Want to Learn more about Equality, Diversity & Inclusion at King’s College London?

- Found out more by visiting our Equality, Diversity & Inclusion at King’s pages.

- Follow us on Twitter.

- Email the team at diversity@kcl.ac.uk