Content Warning: This blog contains references to suicide, self harm & eating disorders that some readers my find upsetting.

The writer wishes to remain anonymous and protect the privacy of those whom the story is about so no names are given and instead ‘our/my daughter’ and ‘she’ are used.

Happy New Year

I am writing this on 24 February 2022, as the world returns to some semblance of normality post pandemic.

Yet I am stuck.

Since about 12.45 am on New Year’s Day my life changed and I am like a swimmer under water.

I was happily seeing in the New Year at a local pub. Chatting to strangers. Watching Jools Holland. My little girl was left at home alone. She felt so unhappy, she took action to cause herself deliberate harm and endanger her life. She is 15. In writing this I have been made aware of and been asked to comply with the Samaritans guidelines to “Steer clear of portraying anything that is easy to imitate, for example where the materials or ingredients involved are readily available and providing details on how it was carried out.” I want to respect this. But I also think it is important for all of you who are parents to know that I have been rebuking myself every minute about how preventable this was. The truth is she didn’t have to go very far to get what she needed, and my complacency and ignorance meant I never considered there to be a risk. Knowing what I know now, I would do things very differently.

Let’s flash back. Over the last few months, we had our suspicions and reports she had been drinking and vaping and she was generally ‘acting out a bit’. At some point in those few months, she had told someone at school she had made herself sick in the early lockdown. We had been to see the GP. Been referred to CAMHS (Children and adolescent mental health services for those lucky enough not to know) and been rejected (not the right kind of eating disorder).

The potential eating disorder and lack of treatment had left me a bit paralysed, but she received some counselling in school and I guess I had put it out of my mind. We had tried talking to her. Tried grounding her in relation to the drinking and vaping. That week (the one between Christmas and New Year) we had found incontrovertible evidence. A part-drunk, 1-litre bottle of vodka and a mountain of vaping paraphernalia. We grounded her again. A reasonable parenting response, I think. We grounded her, having had what we believed to be a constructive and supportive conversation explaining why we were doing that. We see ourselves as liberal, empowering parents.

That is why she is home alone. We asked her if she wanted to do something with us? If she wanted to go out with us. No, no no. I am going to my room.

Every day I question myself about our decisions that day and each decision since. I no longer have confidence in my own judgement.

One of my regular thoughts is what would have happened if we had stayed home? Would it not have happened?

Or would she have called us for help?

Or would she not have called us for help and stayed suffering?

Would we have found her dead in her room – how long would it have been before we went to get her up in the morning on New Year’s Day?

Another recurring thought is, what if she had died?

I am numb now. What would I be doing? How would I be behaving if she were dead? I imagine telling people. I imagine her funeral. I find myself locking myself in the shower, turning it on and weeping.

Back to the pub. I see my partner take a phone call. I see their whole demeanour change. They dash to get their stuff clearly indicating I need to get mine. We leave the pub. They tell me our 15-year-old daughter has taken an overdose. Paramedics are on their way.

They can move quicker than me. I tell them to run home.

I arrive home to our normal looking house. Inside she is sitting on the sofa. She looks fine. There are 2 paramedics in the house. They ask us to sit in the kitchen. One of them comes to talk to us.

Writing this so much later, means I don’t really recollect the details of the conversation. I am sure I don’t believe it. I think it is some horrible hoax. She is pretending. She has made it up. They have made a mistake.

Anyway, both an age and not long after I find myself in an ambulance on our way to A&E. Luckily? She is still a child, so we get to go to Children’s A&E. We wait in chairs. She is messaging on her phone. She isn’t speaking to me. Everything about her body language rejects me. I don’t know what to say. I am arguably a bit drunk. (Let’s not forget less than 2 hours ago it was New Year’s Eve and I’d been living my normal life.)

We see one nurse. Doctor? She asks a load of questions. We return to chairs. Sometime later we get invited into the next bit. We are in a small room with a gurney and a chair. More people, more questions. Blood tests are required. I keep taking myself to the bathroom. I am feeling extremely queasy. I vomit bile – who knows how many times. Blood tests take a couple of hours it turns out.

The questions and the answers – so she took a load of tablets. I hear she then looked up what she should do. She did a ‘quiz’ on the NHS site. She called 111. Paramedics came. She has told someone in this chain she has been self-harming since she was 10. She has been making herself sick when she eats.

She refuses to lie down – she clearly doesn’t want to talk. I am numb – outwardly calm, inwardly beyond confused and upset. I lie down.

Each of the medics seems to ask the same questions. It is never clear to me how much they are asking me. How I should behave or what I should say. The truth is I know so little. What has been happening in her life. Why did she do this? How did she do this? One medic comments we use to see one or two ‘of’ these a month – now we see at least one a night. ‘One of these’ = teenage overdose!

The blood tests reveal ‘x’ level of the substance she took (explained in much more technical language). It was not a lie or a hoax. She needs to receive medicine. Medicine in the form of a drip for 12-24 hours. We are admitted. Thinking about it now, it must have been clear to the paramedics that she was going to be admitted. They had asked her to pack a bag. I too have a bag with ‘the necessities’. I have little or no recollection of how that happened.

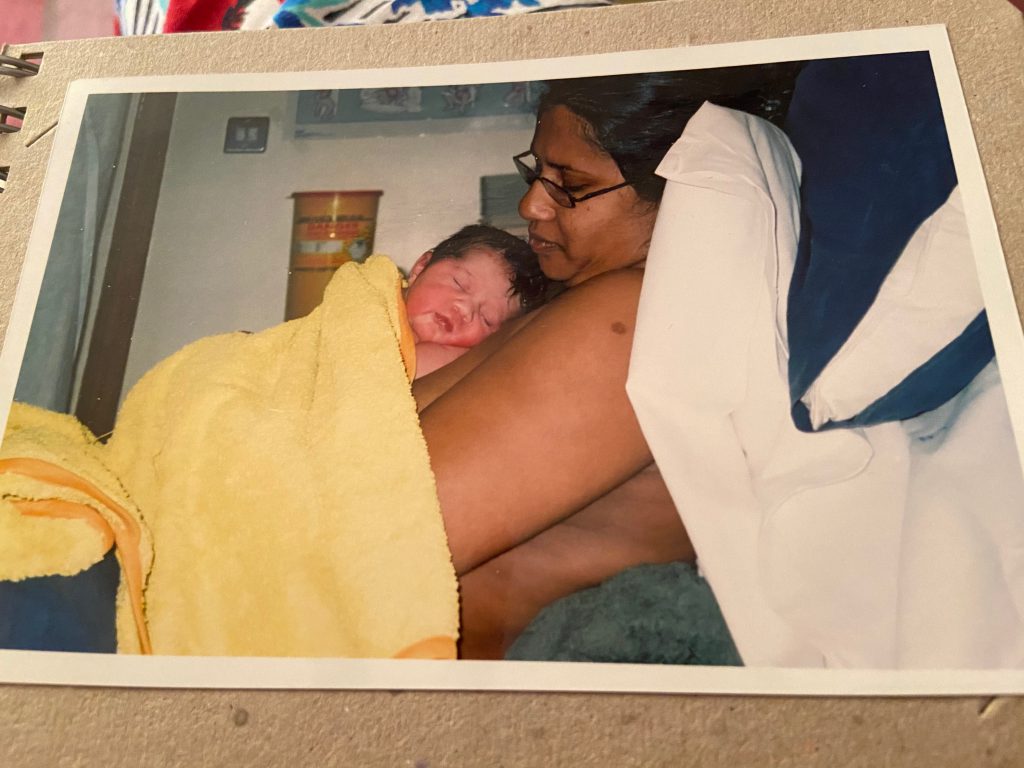

We are on both a children’s ward and what coincidentally turns out to be an eating disorders ward. The pandemic and the mental health impacts has driven the need for extra wards like this. The only moment of softness happens as we arrive in the ward. She looks around. She, for a few seconds, lets her guard down. Her face crumples. Her eyes fill with tears. I climb onto the bed and hold her. I cry a bit and tell her I love her. For a few seconds she lets me hold her. Then that moment ends – and we are separate, pushed apart by the force field she exudes.

The next 36 hours in retrospect were probably the most comforting of the last 7 weeks or however long it is. We were safe. She was on the drip. Doctors, nurses, people looked after us. We ate, slept, watched TV and read. I didn’t have to make any decisions. Me and her father rotated (Covid – only one visitor at a time). I can get tea and toast whenever I want. She occasionally lets me get her toast too.

At some point I get to go home. I clean the house. I shower. I eat. I talk to my other children I can’t sleep though, despite being beyond exhausted.

At the hospital we also spoke to people from CAMHS each on our own and together. They told us we had to make the house safe. Remove all dangerous things from her access. Her dad had to do that. Search her room. He had to remove a sharpener blade embedded in blue tack on the wall. He had to take all the medicine out of our bathroom cupboard. All the cleaning products out from under the stairs.

They (CAMHS) do not think she is mentally ill. It is ‘social stressors’. They recommend counselling. They will check in in 7 days. They do. I get the most useful clear statement at that point. I ask should we just let her do what she wants? No. You have to parent. You must set boundaries. You also have to recognise that this (taking an overdose) is something she is capable of. It confirms my helplessness but also confirms we must carry on trying to be her regular parents. That there are no answers or ways out.

Eventually we went home. She slept. I won’t go through day by day. I am stunned by how life goes on. I haven’t taken a single day off work. Not because I can’t but because I can’t really sit with my own thoughts. Being at work gives me a focus. People meet me every day – as far as I can tell they think everything is fine. I am like someone trapped in jelly or underwater. The world around me moves – I watch it from the stillness of my inner panic and fear.

I socialise. I go away. I do nice things. I remain numb and terrified.

I work somewhere where I could get counselling immediately on the phone. That has been a lifesaver. She goes to a school that is massively supportive and professional. I am having counselling every week. She will start having some properly soon – it’s been ad hoc up till now. The immediate family have been trying to help and support.

Every day I want to burst into her room multiple times a day to check she is there, alive not overdosed, not cutting herself. Every day I wake up and am grateful to have another day with her. Every night I am glad that we have survived another day. Every day I am angry and afraid at myself, at her, at the world. I consume wellbeing and mental health resources constantly. I am still looking for the answer – even though I know the answer is external help and time.

I, until 1 January 2022, was a together person. I supported others and problem solved big world problems. Now I am a robot who walks on eggshells at home, terrified she is going to do it again. Sad and upset that I am none the wiser as to why she is so unhappy.

I wish I could write this to offer light at the end of the tunnel. I am far from the end of the tunnel yet. It is dark and it is cold, and it is lonely. What I have realised is that I must take each day as it comes. That is in fact the only option. I know I must do what I can to look after myself. The counsellor tells me to be available to her – carry on letting her know I care. I try to do that every day. I tell her I love her. I hug her when she will let me. Last night we tried to talk to her. She refuses to talk. I barely sleep. I am today in a daze – the worry is infinite.

I am grateful to have a support system and people I trust. I also know that people mean well and want to help but no-one really can. We live in a country where we got treated and did not have to think about the cost. For that I am forever grateful. We are being supported and yet I do not know if things will ever get better.

The thing I know is I would give pretty much everything I have up to ensure my daughter is safe, healthy and well and to turn the clock back to whenever she became so unhappy that this became a possibility.

All I can offer to readers is, if any of this resonates with you, don’t ignore it; do something and ask for help.

Guidance & Support

- For guidance on mental wellbeing, and details of a range of sources of support, including Togetherall, see staff mental wellbeing.

- For student support visit Student Services Online.

- For external support related to themes explored in this blog you can visit Mind.

(Edited: 30th March 2022.)