In this blog Timothy Ijoyemi, Research Fellow and Equality, Diversity & Inclusion Advocate at Durham University, explores the case for diversity quotas in recruitment.

Of the numerous ways to address BAME under representation in higher education and many other sectors, diversity quotas are among the most controversial. To suggest that a portion of roles within an organisation should be reserved for applicants from underrepresented groups is to invite accusations of unfairness, discrimination, and naivety. After all, shouldn’t a meritocratic society let people rise and fall on their merits? Isn’t it naïve to think that hiring on any criteria other than aptitude and experience won’t negatively impact productivity? This post outlines some of the arguments in support of quotas, as well as research findings that should give opponents pause for thought.

The myth of meritocracy

One powerful argument against the charge that quotas undermine meritocracy is that there’s no meritocracy to undermine in the first place. Power and privilege define the metrics of merit – however reasonable they might seem – meanwhile structural and implicit biases make it harder for members of underprivileged groups to convince recruiters that they satisfy these criteria. Ironically, by helping to level an uneven playing field, quotas could actually bring us closer to the very meritocratic ideal so often invoked to contest them.

Softer methods of increasing diversity don’t always work

Of all the levers available to recruiters wanting to increase organisational diversity, quotas are one of the most powerful. When implemented as temporary measures, they can kick-start progress that might otherwise take decades to achieve, or never materialise at all. There is ample evidence from corporate American, for instance, that ‘soft’ approaches to increasing diversity – including diversity training, hiring tests, performance ratings, and grievance systems – don’t reliably translate to more diverse work forces or company boards. By comparison, stronger “affirmative action” initiatives in U.S. college admissions have had considerable success in increasing admissions of students from underrepresented groups, with one study finding that students of colour were 23% less likely to be admitted to elite institutions in states where legal challenges had succeeded in banning these initiatives.

While quotas don’t necessitate affirmative action – or positive action as termed in the UK’s Equality Act 2010 – they would strongly incentivise recruiters to find and attract talent from underrepresented groups. They would also give a solid rationale for implementing positive action, such as preferentially hiring a candidate from an under-represented group over a non-minority candidate where the two are equally qualified.

Existing BAME talent can meet organisational demands

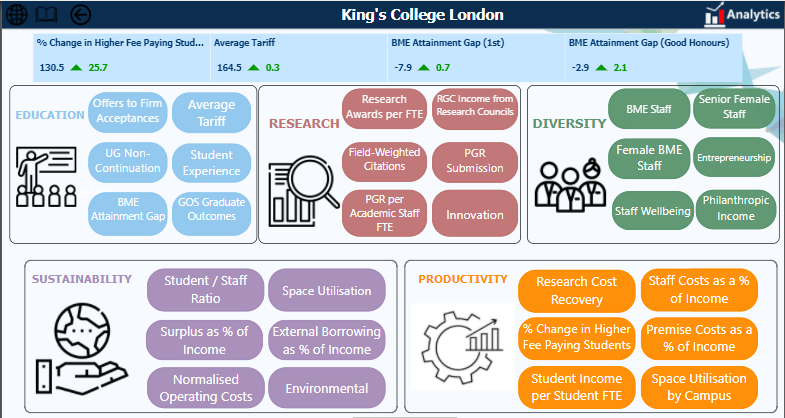

On its face, the concern that quotas would require lowering recruitment standards smacks of prejudice, seeming to rest on the assumption that members of underrepresented groups are less likely to possess abilities that make members of privileged groups generally more suitable for (particularly higher level) organisational roles. A more charitable take is that those expressing this concern know that structural and overt discrimination hinders attainment for many underrepresented groups, seeing differences in hiring rates as a regrettable, but inevitable, outcome. Aside from passing the buck for increasing workplace diversity to institutions dominant earlier in the pipeline (e.g., schools), this attitude reflects a poor estimation of BAME talent. Educational attainment at GCSE is now higher among many BAME groups than white British pupils, while the percentage of 18 year olds from every BAME group entering higher education has risen dramatically over time. Despite this, examples of under representation in the workplace abound. To take just one example, while over seven percent of first year postgraduate entrants in 2017/18 were black, only 0.6% of university professors belong to this group. Diversity quotas would help to close the gap between BAME educational attainment and success in securing commensurate workplace roles.

Initial concerns dissipate after quotas are introduced

Some argue that diversity quotas are simply too divisive to be used. While it’s true that quotas are generally viewed unfavourably by members of privileged groups in the UK, there’s good reason to believe that this is at least partly rooted in suspicion of the unfamiliar. Indeed, research conducted in the U.S. and Europe has found that attitudes of board members towards gender diversity quotas are more favourable in countries with quotas than without. And this doesn’t simply reflect pre-existing differences in opinion. In Norway, even company directors who opposed gender diversity quotas before they were introduced eventually came to view them positively. Far from seeing their fears realised, these directors said that increased female representation on boards had led to better governance and decision making. Considering the numerous benefits that accrue to organisations with more ethnically diverse employees, it seems likely that broader diversity quotas would also be viewed more favourably once their positive effects were felt. Sometimes bold leadership is needed to implement good but unpopular solutions.

Diversity quotas are not a panacea for the barriers to employment that underrepresented groups face, nor are they without controversy. Nevertheless, delivered in a targeted, time-limited way, they could be the shock to the system needed to break through the diversity ceilings that more tepid approaches have failed to breach.