This blog is part of a series celebrating Black History Month 2021 and the theme ‘Proud To Be’.

Aysha Nasir Rao, a third year History Student and Executive Assistant to the Chief Executive of the KCLSU, reflects on this years Black History Month theme of ‘Proud To Be’ and her experience studying the module ‘Investigating the Colonial Past of King’s College London’.

I am proud to be a Muslim.

I am proud to be Pakistani.

I am proud to be a woman.

I am proud to be the child of immigrants.

When I think of what I’m proud to be, these are the first that come to mind. The list could go on and on, but I think the things about myself I carry the most pride in are the things I was taught to be ashamed of, my heritage and faith being two of them.

Being a 90s baby, my formative years took place in a post 9/11 world (I was 5 years old) in Canada where it was definitely not a good thing to be a proud Muslim or Pakistani. This was made abundantly clear to me and my family living in a very small suburban town in Ottawa, where my family’s faces were some of the only brown ones I saw.

Some of my earliest memories are of beautiful Canadian winters, playing in the snow during Christmas time, lights and snowmen lining the streets. But this handful of memories are some of the only happy ones I can recall. The moments that I remember surprisingly clearly over twenty years later are of me in class being taunted by other students, of my teachers not stepping in when this happened, and of this tangible feeling that almost overnight people in my everyday life no longer liked or trusted me or my family. Even as a child I noticed how differently strangers would treat us, and worse how those in our own lives did.

It’s funny the things that leave such a lasting mark on us and affect us years on. That moment for me took place outside my family home. My neighbour was also my closest friend at school and who I sat next to everyday. It used to be a routine for me on the weekends to take my toys to her house and sit and have lunch with her family. This one particular weekend, around a month or so after the attacks, we were talking about her birthday party. She said to me, in the nicest way I think she thought she could, that her parents no longer felt I should be coming over to their house or playing with their daughter anymore. I remember not understanding why, I mean her family knew me so well and had only ever been nice to me, I spent more time at their house than I did at my own most weekends. She mumbled something or the other about what her parents thought of my family, which I assume was shared by the other parents at school because the same thing happened every time a birthday came around in class. Eventually I stopped taking the bus to school, I’d walk to my seat and spend the day not talking or being talked to. I started to learn to be quiet and slowly a sense of shame grew in me.

I think if my parents hadn’t made the decision to leave, I wouldn’t be writing about my pride right now. I credit a lot of this change to the community we made in Manchester. Though I was surrounded by so many different cultures, faiths and faces it was the first time I felt embraced and comfortable with people outside of my family (at the age of 7). I eventually got back in touch with my faith and my culture. I tried to re-learn Urdu, I started praying and proudly wearing my cultural dress, and it felt as though I unlocked another part of me. Like I wasn’t fully me because I wasn’t accepting all of me. And now that I’m in touch with my roots, I’m knowledgeable of my heritage and the incredible shoulders I stand on, I am so proud of who I am and what I represent. A brown Muslim woman.

–

Now as an adult I’ve reflected on how these events shaped me. Though it’s given me a great deal of resilience, once I got to KCL I noticed how much it was still affecting me in a negative way. King’s was certainly a culture shock. Though at the heart of the most diverse city in the world, Strand and more specifically for me the history department, was far from it and I found myself feeling alone and out of place again, a feeling I hadn’t felt at this level since I was a child. It’s not like those in my classes weren’t welcoming or kind, but looking back the last time I felt this out of place and was in a majority white space, I was five years old living in Canada.

I really found it difficult to feel the sense of community others felt and began to look for this at other universities where I felt more comfortable to express myself and where I was surrounded by more black and brown faces. This lack of comfortability was cemented in my first semester for my ‘Worlds of the British Empire’ module. When discussing the significance of Robert Clive’s statue, otherwise known as Clive of India, I shared what I felt his memorialisation represents especially when someone from my background is to walk by and see it. This was met with barely an acknowledgement, a sigh or two and was ultimately brushed off easily by the other students and not touched on again. By the time I was in second year, 2020 finally brought some much needed attention to the Black Lives Matter movement. Though this was brought about by instances of horrific police brutality with the death of George Floyd, and dozens of other black men and women during the summer alone, the world was forced to stop and listen to the conversations that have always been had within family homes and black and brown communities the world over.

Here in the U.K, people were also forced to confront the histories of some of their most celebrated figures, Nelson and Churchill for example, who have deep ties with the slave trade and colonial legacies. I saw some changes being made past appearances at King’s, the creation of the ‘Investigating the Colonial Past of King’s College London’ led by Dr Liam Liburd being one. I again debated the presence of another statue, but luckily to a much more empathetic class.

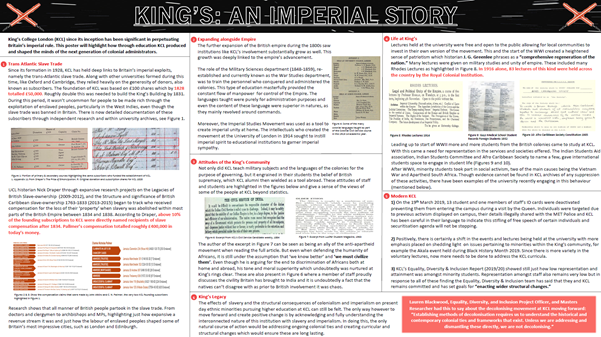

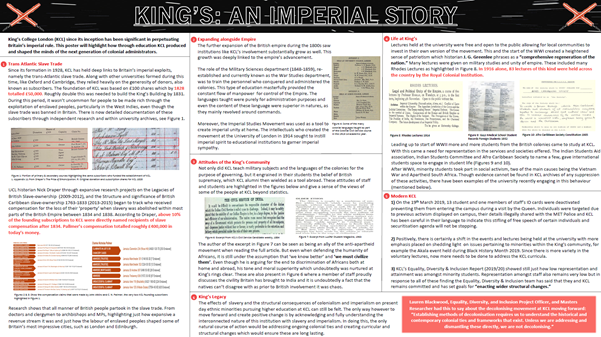

Part of the assessment for this module was to create a poster based on our own research into King’s colonial past through King’s extensive archive (though we were limited due to COVID). Mine, which is attached below, went with a Star Wars theme and likened the British Empire to that of the Emperor Palpatine’s Imperial Army. It serves as a summary of some of my key learnings from the module.

King’s: An imperial story poster

Though it’s only scratching the surface, I wanted to highlight what King’s stood for at its inception but to end on what King’s legacy and what it aims to be now, especially since I am now a tiny part of that legacy. With an institution as old as King’s, Oxford and Cambridge being the only two older English institutions, there wasn’t much doubt that the university I now pay a large sum of money to had a hand in subjugating my ancestors through empire and has its own links to the Atlantic slave trade. Looking at the poster again, it raises the question for me of if we can ever achieve a fully decolonised curriculum at King’s or if those two things are in conflict with one another. It’s an interesting question for all of us to think about.

Being a history module, the class was not the most diverse (to be expected), but Dr Liburd and the other students created an encouraging space for us all to share our thoughts which were respected and not belittled and where empathy was always present. Though Dr Liburd this year has gone on to a great position at Durham University, the module is continuing with Dr Jean Smith. Speaking with Dr Smith earlier this month, it was lovely to hear how committed and determined she was to making this classroom space just as safe and comfortable for students.

For any single or joint honours history students on the fence on selecting this module, I can definitely say you won’t regret it, even if colonial history isn’t your main area of focus. The debates we had in class opened my mind to new ideas, I learnt the histories of abolitionists that were never taught to me in school, I learnt how to conduct research on my own which we don’t get a chance to do until third year, and most importantly, my beliefs were challenged regularly in a way they haven’t been in other classes. And as a bonus, it’s also a welcome break from writing the longform essays we’re unfortunately too used to.

Change always happens slower than we would like, but on the brighter side the History department is in the process of redesigning the first-year curriculum and have just met this week to discuss the second-year curriculum, both with decolonising themes being at the centre of these talks. For me this means in a few years, the history degree will be more attractive to those from minority backgrounds, and they will have a chance at studying a more honest view of world history. On this subject, I was able to have an open conversation with Professor David Brydan about decolonising the History curriculum, what challenges there are and what he sees happening moving forward.

–

Aysha Nasir Rao in conversation with Professor David Brydan

How do you define decolonisation it in relation to the curriculum?

It means different things to different people. The simplest strand is a deep diversification, that there is a diversity of voices in our primary sources, secondary reading and the geographical scope of the topics we cover. Then, on a level up, it is about challenging ourselves on what we teach and the perspectives we teach from. For example, I teach the global Cold War. One of the easiest things to do is to have load of primary sources from all over the world, but the more difficult thing to do is saying that the Cold War is a Western construct and thinking about the second half of the twentieth century as “The Cold War” is a very narrow, western-centric view of that period of history in which the Cold War was one of lots of different strands of things going on, of which decolonisation was one. Thinking about how and to what extent, even if at all, we can think about the Cold War beyond the western lens is not something easily done but is something you must embed into all of the conversations we have in our teaching. And finally, I think with conversations surround decolonisation you have to think of anti-colonialism as well and people who fought against it. Sometimes I worry that the language is a bit too neutral in a way and instead what we should be talking about is anti-colonialism in the same way we talk about anti-racism and an ant-racist curriculum, rather than a de-racist curriculum. And bringing it back to the Cold War, you can easily include a lot on the fight against colonialism in all of its forms and anti-colonialists in the source material.

Do you see or feel that there any roadblocks to having that open safe space within a classroom to discuss conversations such as this?

I don’t think it’s necessarily about specific roadblocks and I haven’t found situations where there are individuals who are hostile to having these conversations. There are a lot of people who don’t care that much and there are people who see these conversations through a hostile lens, but I’ve never experienced that in my classrooms.

I think it’s more about what we have been discussing before where it’s the wider political environment makes people reluctant to engage in the conversation because they fear that they will be misinterpreted or create difficult situations in even raising these topics. It’s such a difficult thing to target because it often comes down to the dynamics of the group and the institutional dynamics and you can’t just pretend it’s like having an open conversation amongst friends where you won’t necessarily be judged. I think working out how we create these kinds of environments is really hard but one if the things I was struck by the other day was the importance of dialogue, not just amongst students, but staff-student dialogue and I was interested by what you said about having these conversations with staff members made you feel more comfortable and changed your perspective as well. I think if everyone was able to have those detailed conversations with us and vice versa, then we would be able to create those environments where people are more comfortable. We’re limited with the time we have with students in a group setting so what we need to do is find a way to almost shortcut that process, for lack of a better word. So dialogue is what I would put the most emphasis on, but I’m not entirely sure how we would create those environments for all students in the little time we have with them in each class.

How would you tackle apathy to these issues within the King’s community?

Again, I would emphasise the process of dialogue. I think if you were to throw the question of decolonisation in with no preparation, then those who are inherently interested in it will already have ideas and those who haven’t thought about it before won’t have a clue what you’re talking about. And so, for the people haven’t been exposed to these ideas before, I think we really need to embed it in the formal conversations we have throughout the year so that people in lots of different classes covering a variety of periods and topics have had these important conversations about what a decolonised curriculum means and what a decolonised approach to their topics means. And through that people will develop. People will not be apathetic because they will gain a greater understanding if its importance, especially in a historical context. And this needs to be a long-term pedagogical process, not something that is just thrown in every now and again in isolation but discussed throughout the modules and built into the curriculum

And I would say, the only times I’ve had unsatisfactory conversations about it has been when I have just thrown it in there without giving students that preparation, and where it has worked well is where there has been an ongoing dialogue.

Are there plans for introducing decolonisation topics for specific modules that are compulsory for history students throughout the course for example, HSSA or History and Memory?

I think faculty members are doing that anyways because of conversations being had by a lot of people, especially more recently. There is currently a curriculum reform process going on in which these conversations re being had in the background, but I wouldn’t say there’s a set strategy where every module will have it set out this way. But I think one of the things we should do is talk to students about that, which is what we’re doing with the redesign of our first-year curriculum, and say ‘this is what we’re doing, what do you think about it, what reading would you like to see, are there any topics you feel we missed etc..’, and then thin king about decolonising the curriculum as part of those conversations would be really useful thing to do.

Do you know if there are any plans to include modules which directly deal with this subject matter, such as Black in the Union Jack or King’s Colonial Past?

We are reforming the curriculum year by year and we are in the process of reforming year 1 right now. We actually have our first meeting about year two this week and this is where students can be more selective in their modules choices and focus on their interests. I don’t have specifics about this, but this is why dialogue like this is so useful, so when it comes time for departmental meetings about reforms to be made all of these conversations can feed into those discussions.

In your time at the department (3 years) have you noticed any change with regards to embracing decolonising movements?

I can see that a lot has changed since the three years that I arrived at least in terms of the modules that I’m aware of being taught, but I also don’t think there’s been a grand transformation either. I think the process was already happening beforehand and it’s definitly an ongoing but slow moving. And so yes is my answer, but I don’t think by any means the problem has been solved. Going back to your first question, this is very much a process and it’s not something where we can do ten things and it’s not an issue anymore. Inherently this is something that must be embedded in our thinking going forward and we will naturally find new and different ways to decolonise the curriculum because the problems won’t always be the same. And we need to constantly be including students because it is a process of dialogue and people’s ideas around this and how to best tackle these issues will change over time, and I think partly changes in the department will come from constantly pressure and dialogue with students.

With regards to having a more representative student body, how do you think we should engage students from underrepresented backgrounds to be interested in history in HE, especially as there is this disparity compared to other faculties?

This is definitely a humanities problem, I think. Generally, History attracts people from higher socio-economic backgrounds whose university choices aren’t necessarily dependent on job prospects straight after graduation, as well as the perception that humanities won’t lead to as well-paid jobs which then feeds into the backgrounds of the students on our courses. But it also has to do with History and the way it is taught in schools and what is taught in schools.

So, with regards to what we can control I think working with schools is really important. I and other members of the department have done a lot of work like this and have these conversations that we’re having but within the school context as well, which is difficult because they’re more constrained by a national curriculum. For example, Toby Greene in the department designed an A-level module on pre-colonial West African history and put together resources for teachers to use with the intention that this is something that schools should be teaching and incorporating, especially since topics like this aren’t available for A-level students to do. So yes, if we can help to decolonise schools in regard to what they’re teaching then that will hopefully feed through to the backgrounds of the students who then come to study history at university. And if your experience of history is studying the Tudors over and over again in school, why would you feel like a history degree is relevant for you.

School teachers have more constraints that at university because they need to get their students to get good grades and they have a curriculum they have to follow and exam boards and so the desire to do this kind of work may be there, but they don’ have the time or resources to do so. I think in university we face fewer constraints and have more intellectual freedom so in that sense it’s easier for us. However, we do have institutional constraints. For example King’s at the moment thinks that we should have fewer modules and all modules should be run by multiple members of staff, so that for example constrains to some extent what we can do, but we still ultimately have the freedom to teach what we want. But also, for us I think the constraint is also a time constraint because it can take quote a long time for change to happen especially since it’s all very collegiate and there are processes to follow which ultimately delays things. Partly, there’s also a degree of institutional inertia in that it’s easier to teach things you’ve already had to teach and kept the same than it is to prepare new courses every year which teachers don’t always have the time to do that especially when a lot of staff are early in their career and people are on fixed-term contracts, they are normally coming in a picking up pre-existing courses rather than having the time to design their own.

The publication you were a part of in 2019 raised the problem of syllabi struggling to keep track of re-interpretations of history and thus teachers resorting to teaching the history they were taught at school. How do you think can we integrate new ideas and topics into these very familiar narratives?

The teaching and learning document we did was a collaboration between historians and schoolteachers, and it was written for the Historical Association for schools. It was published three years ago but the initial thoughts to do it started about five years ago.

I don’t think we talked a lot of decolonisation in this, but we certainly had thought about it. I had written about the Cold War, and I tried to write about the Global Cold War and introducing decolonisation topics into that. But the interesting thing about this is that I think if we wrote it now, we would do it differently and I think both the academic historians and the teachers who contributed to it would have possibly put more emphasis on Black history, history of migration and on decolonising the curriculum generally because these conversations have been more prominent in the last five years.

I think reading it, it was quite ahead of its time but also so much more has changed especially with what has been brought up in the world with the BLM movement and so on. It suggests how fast things can change and how slow some of these processes are because when this was published it was thought to be cutting-edge research to give to schoolteachers but now the world has changed so much and suddenly doesn’t seem so cutting-edge and needs to be re-evaluated.

And we don’t know what’s going to happen in the world in the next five years and the way we understand history is always shaped by what is going on around us and so this is very much going to be an ongoing process.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

I think I would just emphasise the dialogue point. I think it’s easier to think that this is something for academics to do and that it has to be a top down process but if we’re talking about decolonising the curriculum as a shift in power dynamics that extends to the classroom as well, it has to be partly about democratising the curriculum to a certain extent and integrating the views and ideas of the students in dialogue with academics, a kind of partnership model of education and curriculum reform. This might sometimes be quite difficult to do practically but I think that dialogue and collaborative working is so important.