Vanessa Boodhoo from Chestnut Grove Academy, pens a blog on the importance of understanding and appropriately responding to systemic racism.

Following the death of George Floyd, a 46-year-old African-American, protests against systemic racism and police brutality have scattered across all the 50 states of America alongside other 18 countries. The death of George Floyd particularly sparked the protests but the protesters continue to walk down the streets remembering Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Michael Brow, Breonna Taylor, Stephon Clark, Walter Scott, Anthony Baez, Ahmaud Arbery, Philando Castile, Eric Garner, Dion Johnson, Trayvon Benjamin Martin, Kajieme Powell, James Scurlock, Tony McDade, Elijah McClain, Belly Mujinga, Mark Duggan, Cynthia Jarrett, Leon Briggs, Habib Ullah, Joy Gardner, Kingsley Burrell and many other Black and Brown victims of racism and police brutality in the USA and UK.

As the protests grew many opponents of the movement started to be more vocal. One of their arguments is based upon the belief that the movement “Black Lives Matter” promotes inequality as “all lives mater”. The Black Lives Matter movement was created in 2013 to campaign against violence and systemic racism towards ALL Black people and has since become international. They’ve been actively fighting against racism through the organisation of protests and promotion of policies such as the end of the broken windows policing. None of their policies would disadvantage white people but they would certainly create a safer environment for Black people by reducing racial stereotyping and police brutality. In the US, Black Americans are 30% more likely to get pulled over by the police and although they roughly consist of 13.4% of the American population, they make up 40% of the prison population. As of June 2020, Black people continue to be the largest percentage of victims of police shootings in the US. Similar statistics also apply to the UK: in 2017-2018 Black people were victims of 12% of use-of-force incidents although they account for 3% of the UK population. Furthermore, between April 2018 and March 2019, there were 4 stop and searches for every 1000 white people and 38 for every 1000 Black people. Everyone’s life matters, the BLM movement is simply trying to concentrate on issues that affect the Black community disproportionately, that is why the “all lives matter” statement is so harmful.

Many people are arguing that police departments should be defunded. This defunding wouldn’t be immediate; the change would be gradual and the money taken could be reallocated to create more jobs, to improve the provision of mental health care (around 50% of all inmates in the US have been DIAGNOSED with a mental illness), social programs, experts on drug abuse and housing alongside other “non-police solutions to the problems poor people face”. During these past years, the US has defunded education, Planned Parenthood, health care and public transport; it would not be so radical to spend less money on the police. Eric Garcetti, LA’s current mayor has been planning to cut $150 million from the police budget to invest it in Black communities. The Minneapolis council also decided to defund and dismantle its police force as they concluded that a reform wouldn’t suffice.

Due to systemic racism, BAME communities face discrimination and inequality in terms of employment, education, income, political power, housing, healthcare and many other aspects. A 2018 study revealed that minority ethnic groups in London earn 21.7% less on average than white British employees. Having unequal employment opportunities leads to lower incomes (1/5 children in Black households’ lives in consistent poverty) and lower incomes lead to indecent housing, lower quality of healthcare and education. Undoubtedly, a white person’s life can be hard, but their skin-colour can’t possibly make it harder.

The idea that white privilege doesn’t exist is one of the many examples of ‘white fragility’. Although the noun ‘fragility’ is a synonym of ‘weakness’, white fragility holds an incredible amount of power. In order to avoid any conversations about race, white people often respond in the ‘colour-blind’ or the ‘colour-celebrate’ way. The ‘colour-blind’ often have responses such as “I see beyond skin-colour”, “I was taught to treat everyone the same” or “racism is in the past”. All these responses belittle the existence and experience of racism. The ‘colour-celebrate’ tend to use phrases such as “I am not racist, I have black friends” or “I am not racist, I have POC in my family”. These kinds of responses make it so much harder for people to talk about their own experiences with racism. In 2019, Stephen Ashe conducted a report in Manchester with a sample of 5000 employees. He discovered that 40% of them were victims of racist incidents and when they tried to report them, they were either ignored or labelled as “trouble-makers”. Refusing to talk about race because it makes white people “uncomfortable” suggests that a white person’s comfort matters more than a person of colour’s oppression and discrimination. It is important to talk about racism. Educate yourself, talk about it with your friends and your family, by avoiding the topic we won’t achieve anything.

In times like these, we must be careful of the news we consume. In America when several people gathered carrying weapons and spitting on police officers’ faces to protest because they “needed a haircut”, Trump described them as “very good people”. However, when Black people and their allies started to protest systemic racism and police brutality, Donald Trump didn’t hesitate to refer to them as “thugs” and “bad left radical people”. The contrast between the media representation of the protestors as all violent and the videos coming out of the protests showing peace and violence being enacted on them is stark. This week, several UK news headlines have been about a second wave of C19 and included images of Black protestors, rather than images of predominantly white people crammed onto beaches.

Due to recent events, Britain is waking up to the impact of its colonial past. Recently, the statue of Edward Colston, an English slave trader responsible for the transportation of approximately 84,000 enslaved African people, was pulled down in Bristol with many recognising the pain that its existence had caused for years. It is clear that more needs to happen to ensure that ALL schools learn about Black history and Britain’s colonial past and present.

We cannot stop protesting now that all the police officers involved in George Floyd’s murder have been arrested. We are protesting systemic racism and police brutality. The two still exist. Little effort has been made to dismantle them. We must continue to spread awareness, the fight against racism is not over.

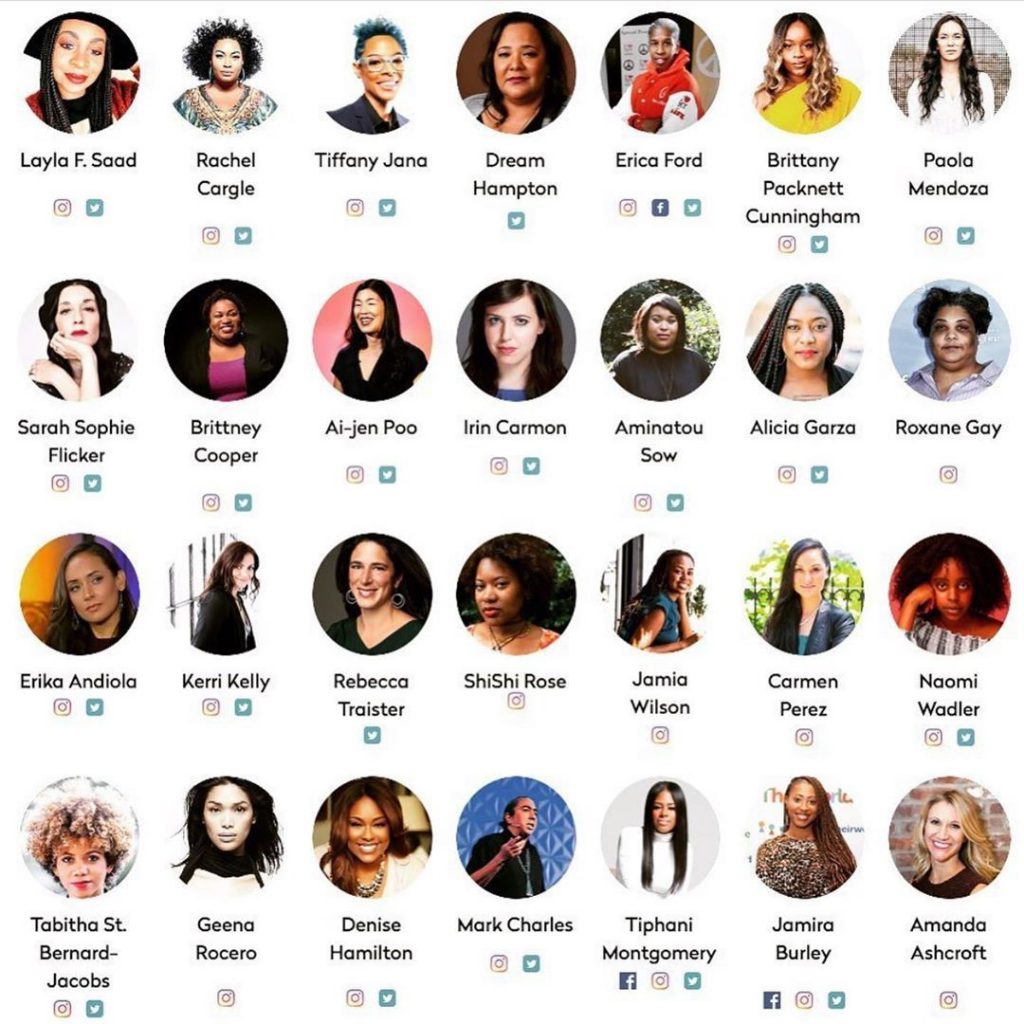

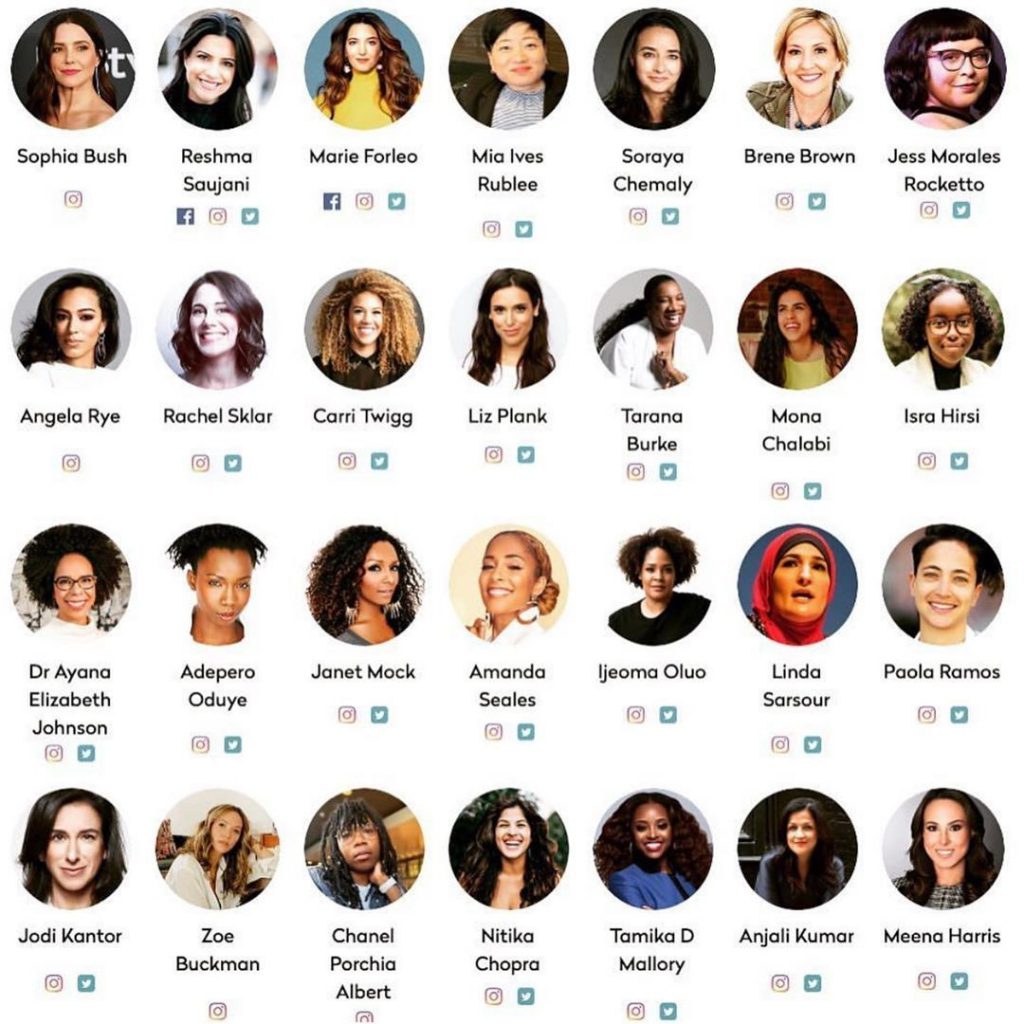

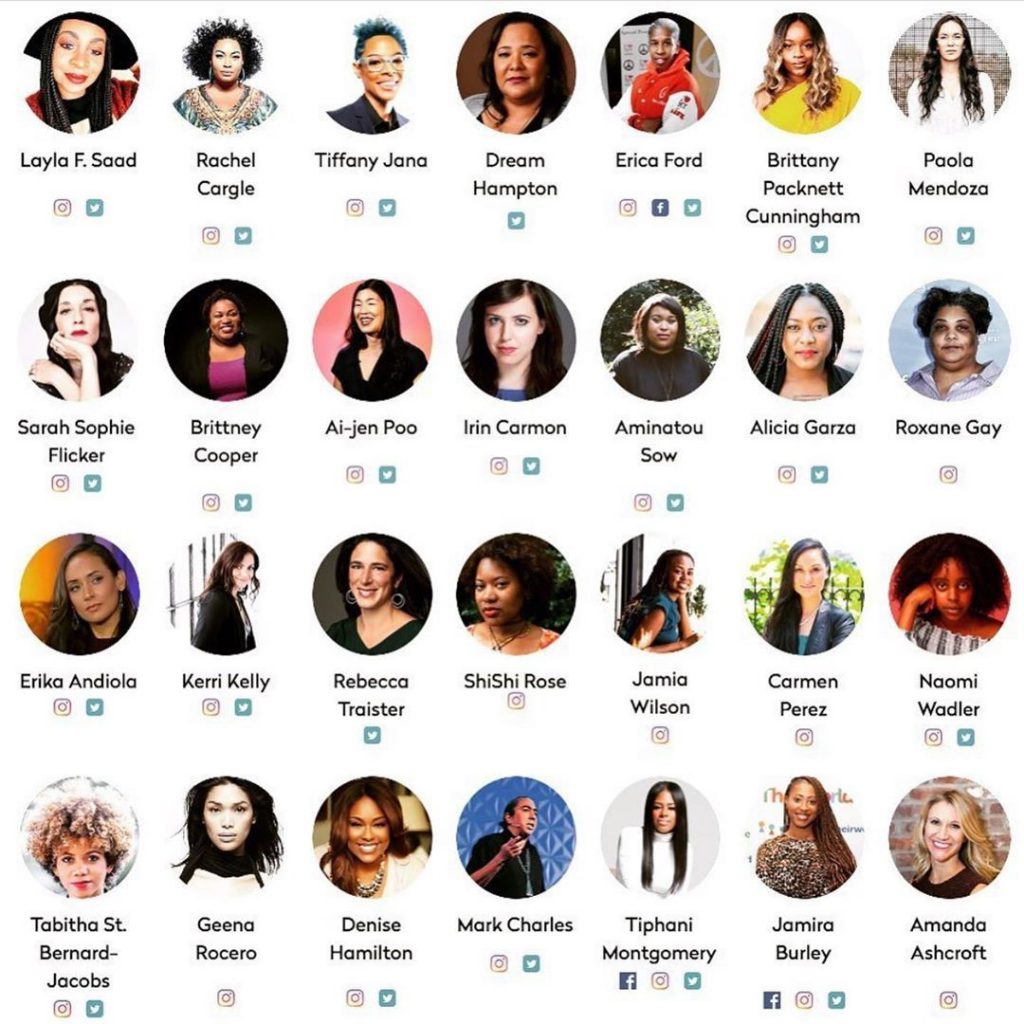

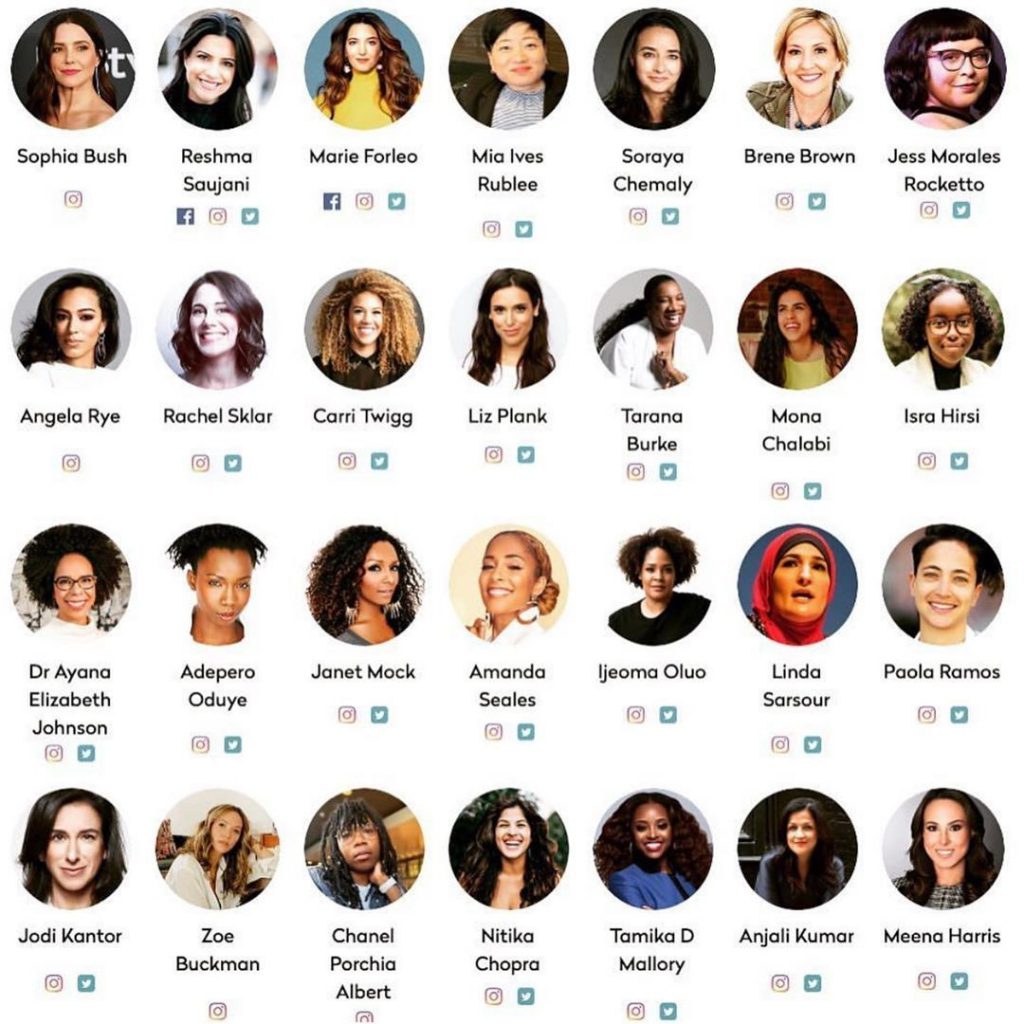

If you’re interested in learning more about race and race equality, here are some activists which the author recommends: