Kendall Robbins is a first-year student nurse at King’s who has Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (Hypermobility Type). Reflecting on 10 years working in the Arts, she considers how Disability Arts and the Social Model of Disability can contribute to future healthcare practice and the building of an inclusive world.

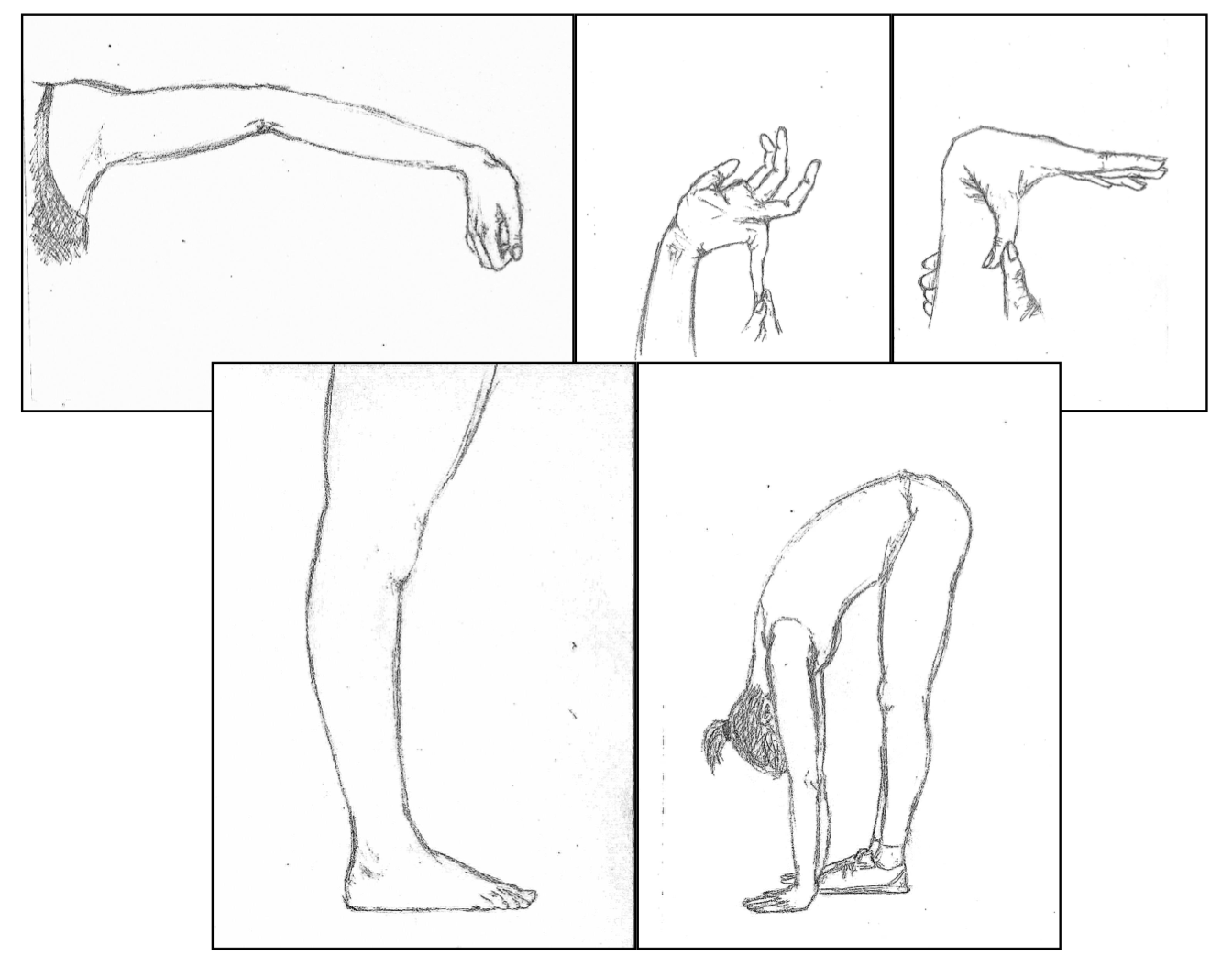

An illustration of the Beighton Scoring System, a screening system commonly used to assess joint hypermobility. Illustration by Aleksandra Lacheta

Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes (EDS) are a family of 13 inherited conditions causing weakened connective tissue. Connective tissues are the building blocks of your body, supporting your skin, blood vessels, organs, muscles, tendons, ligaments and bones. If those building blocks are faulty or weak, they can cause widespread issues. In EDS this manifests as a range of symptoms and comorbidities – additional conditions that frequently co-occur with EDS – ‘double-jointed’ or hypermobile joints, stretchy skin and poor wound healing, disabling and chronic musculoskeletal pain, frequent dislocations, dysautonomia, cardiovascular problems, gastrointestinal disorders, anxiety disorders, swallowing and throat dysfunction, mast cell activation syndrome and urological dysfunction and prolapse – just to name a few.

The average diagnosis period for EDS is 12 years from the onset of symptoms. I remember it starting when I was 5. My mom took me by the hand, and my arm just dislocated. It was at the age of 28 that more limiting symptoms began to appear, sometimes so badly that I would need to lay down under my desk at work. My friends and family thought I was a hypochondriac. One doctor told me it was stress and I needed a life coach. Eventually a diagnosis of ‘Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome – Hypermobility Type’ from a renowned specialist gave my pain and discomfort credibility. I was told I was considered disabled under the Equality Act, a 2010 UK parliamentary act that names 9 ‘protected characteristics,’ including disability, sexuality and race, to legally protect people from discrimination in the workplace and in wider society.

At the time that I received my diagnosis I was working at the British Council, managing global cultural projects in architecture, design and fashion. I was a design expert and had led projects which looked at the problem-solving power of design. Through my job, I started to work with the Unlimited disability arts commissioning platform, who first introduced me to the Social Model of Disability. Before, I had understood disability through the Medical Model, which suggests a person is disabled by their impairments or differences, and it is the role of healthcare professionals to ‘fix’ this. According to the Social Model, someone is disabled by barriers created by society rather than by their impairment or difference. This changed the relationship I had with my condition.

I left my job at the end of 2019 when I became physically unable to continue working in an office. I wanted a new career in which I could explore concepts of care with others experiencing barriers. This is how I came to join King’s as an Adult Nursing student. Sometimes I feel like a spy listening in on lectures describing conditions and hearing future healthcare professionals being taught to interact with individuals experiencing illness. It can feel very othering to sit through a lecture describing orthostatic hypotension, while in my head I am screaming ‘I know what that feels like!’

Since starting my Nursing training in September last year, we haven’t talked about disability in depth or explored concepts like the Social Model. Perhaps this isn’t surprising given that 2.9% of non-medical/dental clinical staff, 1.2% of non-consultants, and 0.8% of consultants in the NHS have declared a disability. If these self-declarations are accurate, then there’s actually very little lived experience of disability within the NHS workforce. Alexandra Adams, who will be the NHS’s first deaf-blind doctor, has spoken out about the discrimination she has faced whilst training to become a medic.

Indeed, the Social Model was developed by disabled people who suggested that healthcare was trying to fix them, unhelpfully framing disabled bodies as the problem, and not accounting for the agency of disabled people. I strongly believe that the Social Model of Disability should be explored in healthcare education; healthcare practitioners need a toolbox that helps them to understand the experience of illness and connect with disabled people in a collaborative way to identify barriers.

Raquel Meseguer / Unchartered Collective – A Crash Course in Cloudspotting (the subversive act of horizontality)

Alongside the activism out of which the Social Model developed, Disability Arts emerged, encompassing art practices in wide-ranging media that focused on telling human stories about disability. Disabled artists continue to offer up their experiences of healthcare and illness, giving visibility to some of the perspectives of the 18.4 million people across England with a long-standing disability or illness.

Dolly Sen’s Mental Health Signposting work takes viewers on the journey of being signposted to mental health services. Raquel Meseguer and Unchartered Collective’s A Crash Course in Cloudspotting challenges the social conventions around rest in public space by inviting audiences to partake in public rest and experience the stories of those who need to do it. Christopher Samuel’s Welcome Inn invites visitors to sleep in at the Art B+B Blackpool and experience inaccessibility firsthand.

Welcome Inn, a sleep-in installation that is difficult to stay in by artist Christopher Samuel. Photograph by Claire Griffiths.

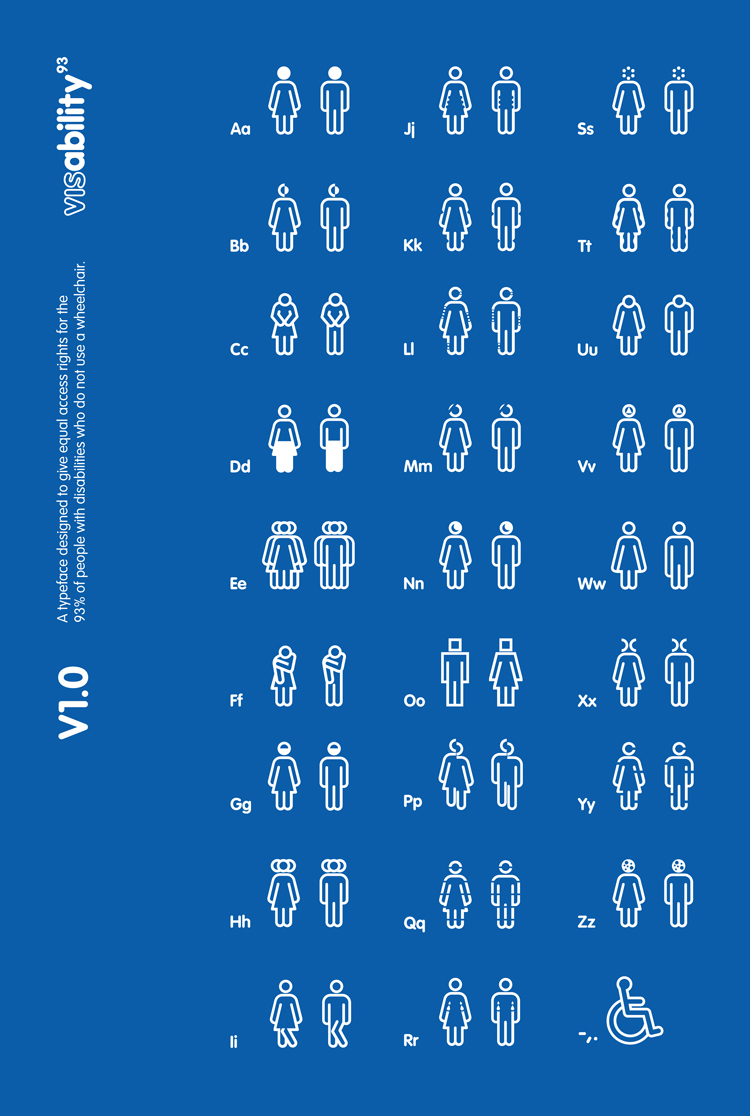

Projects like Visability93 challenge stereotypes of disability, while Sport England’s Mapping Disability: the Facts gives a clear picture of the spectrum of barriers people are facing.

A typeface created for the Visbility93 campaign designed to represent the 93% of disabled people who do not use a wheelchair.

I think many people still imagine disability through the narrow perspective I previously did. The Social Model of Disability opens discussions about how we care for each other as a society, and how we might do this better. It makes space to unpack individual experiences, whether already diagnosed or not, and to consider the pains and pleasures of disabled life in three-dimensional social reality, going far beyond the medical mitigation of symptoms. Alongside a critical understanding of disability models, disabled artists can offer future healthcare workers a different understanding of the meanings of disability and care. Embedding this approach early on in medical education could help to ensure that care and interventions start from the point of recognising barriers and collaborating to build a world that includes everyone. In my opinion, this would transform the experience of disability.

Further reading:

- EDS ECHO: For healthcare professionals who want to improve their ability to care for people with EDS and HSD

- Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes Toolkit for GPs

- NHS Employers: Understanding Disability

- NHS Employers Disability History Month campaign

- A history of disability from a Disability Arts perspective

- NDACA (National Disability Arts Collection & Archive)

- The Social Model of Disability explained by Shape Arts

- Unlimited Disability Arts commissioning programme

- Disability Arts Online

- The Centre for Disability Studies

- Disability Visibility: Politics, Culture, Media podcast

- Rare Disease Day: 28 February