Six members of the King’s English Department have pulled together a list of the books, poems, and writing that have been inspiring them during lockdown.

1. Michael Collins, Senior Lecturer in Twentieth-Century American Literature and Culture

Poe’s work casts a long, dark, and twisted shadow over modern life. Yet with its willfully “perverse” (“The Imp of the Perverse”) humour and wild imagination it can also be a great companion in harrowing times. Here was a writer who certainly knew how crushing boredom could be (“The Black Cat”)! The ache of impotently watching time pass (“The Pit and the Pendulum”). The peculiar rituals that emerge when societies suspend normal rules of conduct (“The Masque of the Red Death”). Want more convincing? He practically invented the modern detective story (“Murders in the Rue Morgue”), pioneered sci-fi (“Hans Pfaall”), and anticipated Big Bang Theory (the physics thing, not that obnoxious show about geeks…) with his prose-poem “Eureka!”. His creepy presence can be felt across so much American culture, from The Simpsons (now all available to stream on Disney+ and also worth your time!), to the novels of Herman Melville, Shirley Jackson and Toni Morrison. Welcome him into your life, invite the darkness, and as he writes in “Murders in the Rue Morgue” “be enamoured of the Night… and into this bizarrerie, as into all his others… quietly [fall]… giving… up to… wild whims with perfect abandon”.

2. Rowan Boyson, Senior Lecturer in Eighteenth-Century and Romantic Literature

I’m currently reading Studs Terkel’s Hard Times, which is an oral history of the Great Depression of the 1930s, first published in 1970. Whilst I work on Romantic poetry, I am also particularly interested in politics and economics, and often teach these themes through the history of literature. I wanted to get a sense of how it feels to live through such a severe crisis. Terkel, a gifted listener, captured the voices of a huge variety of people – from those who were destitute, to wealthy socialites who were barely affected. Whether rich or poor, some interviewees remembered the Great Depression almost nostalgically, as a time of simple needs and camaraderie; others remember hunger, shame, guilt and fear.

3. Josh Davies, Lecturer in Medieval Literature

One book I can’t stop thinking about at the moment is Jay Bernard’s Red and Yellow Nothing. Published in 2016, it is a long poem that reimagines the medieval story of Sir Morien, a figure from Arthurian legend whose father was one of the Knights of the Round Table and whose mother was a “Moorish” princess. Bernard describes the poem as ‘an inquiry into the idea of blackness in Europe before it became synonymous with a less romantic history.’ In the process Bernard draws on a range of medieval and modern material, from folk songs and history to Kendrick Lamar’s good kid m.A.A.d city. The result is a fascinating, astonishing and moving piece of work that has much to teach us about how history and memory can help us give meaning to our experiences of the world.

4. Ruth Padel, Professor of Poetry

I started with a lot of re-reading. First Camus, The Plague, even more brilliant than I remembered. I didn’t realise how deftly the disease mirrored diseased politics. His plague is an allegory for the German occupation, which he experienced in France while his partner was in Algeria. The New York Review of Books is releasing its archive during lockdown, and Tony Judt’s 2001 introduction to it is even more spot on for today.

But Camus read a lot of plague literature and prefaces the novel with a quotation from Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year, which I also re-read, not having realised that he was only 5 during the Great Plague. He did not see it, like Pepys, but was writing a vivid historical novel based probably on his uncle’s journal. ‘Defoe’s novel shows us that behind the endless remonstrances and boundless rage there also lies an anger against fate,’ says Orhan Pamuk, currently writing another historical plague novel.

Then I moved on to Marquez, Love in a Time of Cholera. I am in lockdown with my daughter, a Colombian anthropologist, and my Colombian son in law, and what I had not realised about this brilliant novel, my favourite of Marqez, was that ‘cholera’ is also a pun on cólera, anger (political variety, again). It is another historical novel: the (now) 60 year armed conflict is simmering away in the background as the characters live their colourful tragicomic lives in a richly faceted society.

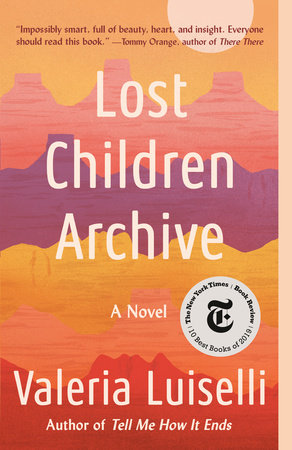

Finally, the new novel I have read completely knocked me out. The Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli, is a stunning, engaging, modernist novel which presents the appalling treatment of unaccompanied child refugees from Mexico in the US as a natural a follow-on from the extermination of the Apaches. Everyone should read it, for its voices, originality, devastating picture of America today, especially in Trumpian states, and what it is saying about real people living real lives, about parents, children, marriages, dreams – and the world today.

5. Clare Brant, Professor of Eighteenth-Century Literature & Culture

During lockdown I was given a beautiful book: Thomas Gray’s poems, from the Riccardi Press. It’s a handsome edition of 1937, vellum bound and with special typography. I thought I knew Gray’s poems reasonably well – I teach Gray’s Elegy in a Country Churchyard in an undergraduate module – but when you read afresh in a differently set edition, you can discover new pleasures. So I recommend Gray’s ‘Hymn To Adversity’, which crescendos to a terrifying vision of ‘screaming Horror’s funeral cry/ Despair, and fell Disease, and ghastly Poverty.’ Seems horribly familiar in Covid-19 times. But the poet adds a final stanza which is much gentler – towards himself, and what he might do to encourage equanimity, or what we might call wellbeing. In this time of relentless Adversity, I recommend this poem, and any poetry that makes you feel better.

6. Luke Roberts, Lecturer in Modern Poetry

Maybe because it’s hard to keep track of time in the crisis, I’ve found myself turning to diaries. First it’s the Journals of the Goncourt brothers, who recorded literary gossip and high society scandal in 19th Century France. Melancholic, neurotic, a little vicious, impossible, reactionary: the Goncourts understood that they were part of a world that was falling away, heaving itself into modernity. I’m sure they were terrible company; but they suit my mood.

James Schuyler’s diaries, a hundred or so years later, are also melancholic, also funny. Schuyler was a poet, often lonely, sometimes secluded in psychiatric hospitals for long stretches. The greatest thing in his diary is his descriptions of the light and the sky, always surprising and always exact. He teaches you how to look out of a window. His poems do this too, but sometimes prose is less demanding.

Lastly, the diaries of Lou Sullivan, recently published as We Both Laughed in Pleasure, are an amazing document of social history. Sullivan’s life as a trans man in the 1970s and 1980s was simply heroic. Or maybe it’s testament to a whole movement of heroes. Either way, it’s a privilege to read the work of someone changing the possibilities of what kind of life can be lived. Lou is brilliant company: generous, tender, and heartbreaking.

Maybe now is the perfect time to start keeping a diary, while nothing is happening and everything is happening, day after day after day.

Read More:

To read more about the experiences of being an English student, check out some of the best MA English modules, and Safia’s day in the life blog post.

King’s English Department page has lots of resources for undergraduates, postgraduates, and more!

Leave a Reply