This piece was originally posted on the London NERC DTP blog. Several of our King’s Water PhD students are supported by the Doctoral Training Programme. Here, third year student David Smedley shares his experiences working on an interdisciplinary team during fieldwork in the Volta.

There is something strangely satisfying about conquering a full day of dirty, dusty fieldwork in the thorny African bush, in the kind of heat that cooks your lunch for you if you forget it outside. True story. Surviving hacking out soil samples in 45 degrees for many many hours does give you a serious sense of achievement and some epic tan lines to go with it, but why this trial by sunburn?

Photo copyright David Smedley

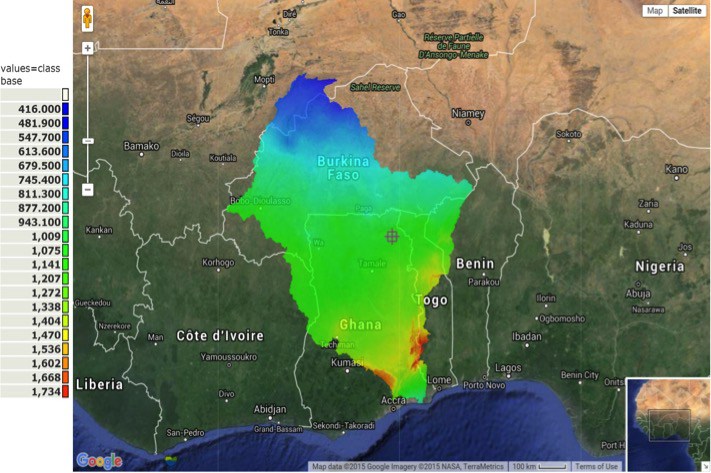

This particular field trip, to a section of the Volta river basin located in northern Ghana and southern Burkina Faso, aimed to collect baseline data for my PhD, as part of a larger project to improve livelihoods amongst smallholders, as well as the health and functioning of the ecosystems in which they exist. The Targeting Agricultural Innovation research group, part of the CGIAR Water Land and Ecosystems research program, is investigating agricultural systems with the duel ability to increase water use efficiency and enhance ecosystem services. Ecosystem services being those services provided by nature which society draws on, such was food, clean water, pollination, flood control, nutrient cycling and so on.

Smallholders dominate much of the landscape in Volta, where most exist in a state of extreme poverty. However, the ability of these small-scale agricultural systems to meet the demands of growing populations is under severe stress, as changing climates and rainfall patterns conspire to limit farming yields, with a devastating effect on local livelihoods.

Photo copyright David Smedley

My PhD is investigating the potential of zai, a traditional water harvesting technique used in the northern drier regions of the basin, to enable farmers to overcome dry spells in the growing season. This would allow them to increase their resilience to rainfall variability and increase crop yields, while also potentially having a positive effect on hydrological ecosystem services. In April 2016, members of the TAI team representing a host of institutions based in Europe, Africa and North America, congregated in the White Volta sub basin to collect a range of data. The linked blog post gives a great break down of the overall team’s activities.

For the purposes of my research, the aim of this field trip was to collect of soil samples and infiltration data (that rate at which water infiltrates into the soil), which will be used as a baseline indication of the soil’s ability to capture and hold moisture. Samples were taken at seven sites across the TAI study area in Burkina Faso and Ghana and then processed back in the lab at Kings College London. The full meaning of this data will only be apparent once a full field trial over an entire growing season has taken place, which will kick off later this year in South Africa. However, one unexpected result was a high organic matter content at a number of sites, which is encouraging as this indicates better than expected soil health.

Weather stations

Another aim of the trip was to demonstrate a FreeStation to a number of potential local partners. FreeStations, designed by Dr Mark Mulligan, are weather stations designed to generate reliable climatic information at the lowest possible cost, using open source hardware, software and 3D printing tech. A demo station was put together by Mark, Sarah Jones (of Biodiversity International & KCL) and myself and demonstrated to a range of potential partners from schools to local water managers. Since then, six more stations have been deployed by Sarah in the Volta and a further six are due for deployment in South Africa alongside my own field trials. The general response to the stations was extremely positive, and local partners clearly recognised the need, with large data gaps existing in weather records, particularly for the developing World.

Photo copyright David Smedley

The pricelessness of interdisciplinary teams

Spending time in the field with a multidisciplinary team, capturing data with everything from ground penetrating radar to drones was a fantastic experience, and not just because I got to use the drone for hours on end. Discussions while traveling or at the daily debrief and dinner table are where real conversations take place that immensely broaden your understanding of both the complexity of what it is you are tackling and what you can achieve by doing your bit and integrating it effectively with a larger team.

Field trips like these give rise to situations where ideas and suggestions flow, and these can be debated and tested in real-time, which is something unique. They also force a broad array of scientific disciplines into a confined space, where each individual has the opportunity to practically understand what the others are trying to calculate and achieve. The value of this from both a learning and, even more simply, from an appreciation point of view, is priceless.

Moving forward

For my own PhD the next step is to run a field-trial testing variants of zai under higher than normal rainfall conditions. The trials will monitor soil moisture, climate (using our FreeStations) and the health and final yield of the crop – maize. Simultaneously, I’ll be conducting a social study investigating the potential for creating climate data collection networks amongst farmers. Finally, on completion of the field trial, WaterWorld will be used to model the impacts of zai at larger scales, and predict what the large-scale adoption of the technique will mean for basin-wide hydrology.

References

1. Mulligan, 2016. Results from the WaterWorld Policy Support System [v2].

2. Google Earth Pro 7.1.7, 2016. Volta River Basin, 9°30’28.16“N, 0°46’05.90”W, (accessed 7.14.16).