Christy Burzio, LLB, BVC , LLM, ACIARB, PhD Researcher at King’s College London

British Telecommunications Plc (Appellant) v Telefónica O2 UK Ltd and Others (Respondents) [2014] UKSC 42 (Supreme Court)

The parties to this case were British Telecom’s (BT) who appealed a decision which found in favour of four mobile network operators (MNO’s).[1] This case raised issues of great importance to the telecoms industry, to its regulators, and indirectly to millions of consumers.

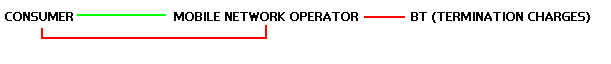

The Green line of telecommunications represents a consumer dialling a standard phone call which is provided by the Network Operator.

The Red line of telecommunications was at issue in this dispute. Here the Network Operators must, pay charges to BT where calls to 080, 0845 and 0870 numbers are called.

The difference in charges:

| FIXED LINE CALLERS | MOBILE CALLERS |

Normal Charges from fixed line callers are as follows:

|

In this instance the Terminating Communication provider will collect termination charges from the Communication Provider from which it received the call. However where calls originate from a mobile network operator, that operator will commonly charge the consumer more than standard local/national rate as shown to the left. |

The Facts

In 2009, BT notified the MNO’s of its revised scheme of termination charges for 08 numbers. The issue was that:

MNO’s would be charged at a rate which varied according to the amount which the originating mobile network charged the caller. The higher the charges to the caller, the greater the termination charges. [2]

The new tariff was not welcomed by the MNO’s and the dispute gained momentum; the action continued for 5 years. In response to the MNO’s pleas, The Office of Communications (Ofcom) had disallowed BT’s introduction of ‘ladder pricing’. The Competition Appeal Tribunal (CAT) overturned this decision, whilst the Court of Appeal (CoA) upheld Ofcoms assessment. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court and a judgement was reached on 9 July 2014.

The Law

1. What was Ofcoms remit to scrutinise the Termination Charges?

The dispute resolution jurisdiction of Ofcom can be found in both Article 20 of the Framework Directive 2002/21/EC[3] and Article 5 of the Access Directive 2002/19/EC.[4] This is further enforced by Sections 185 to 191 of the Communications Act 2003.[5]

Price control, with intervention from regulatory bodies, is important to such a market where there is inefficient competition. It cannot however be imposed by regulation against a mobile network or communications provider without Significant market power (SMP).[6] Regulators can nevertheless intervene, where the emergence of a competitive market is liable to be hindered by a communications provider implementing prejudicial terms into their intercommunication agreement. However, to achieve scrutiny under these provisions one has to bear in mind the regulatory remit of Ofcom which can be found in Art 8 of the Framework Directive as, effective competition, promotion of open markets and the protection of consumers.

2. The Interconnection Terms

BT had, as a prima facie basis, a contractual right to vary its charges. Clause 12 of the Standard Interconnection Agreement, which all parties signed, confers a unilateral power to BT to fix or vary its charges, within the limits of the agreements objectives and directive policy objectives (as above).

The Judgement

Giving high regard to the contractual rights of BT, Ofcom at first instance, found that it could not disallow the variation unless it finds that such terms were inconsistent with the Article 8 objectives. The test was therefore whether interconnection terms are ‘fair and reasonable’ in the sense of having appropriate regard to the regulatory objectives. This seemingly tied the hands of Ofcom, as it was made somewhat clear that the interpretation of Ofcoms role was not to impose what it thought was the best regulatory solution, but to adjudicate upon the parties contractual rights and then determine whether there is any positive regulatory reason to depart from the contractual position.

On the basis of this legal foundation the Supreme Court found that there was no justification to disallow BT’s ladder pricing. BT had a contractual right to introduce it, and there was no sound evidence that such an introduction was inconsistent with Article 8 objectives.

In applying the welfare test, Ofcom did not find conclusively that such a change could result in a disbenefit to consumers. It stressed that the welfare assessment was inconclusive, not that consumers would be harmed, adding that an undue fetter on BT’s commercial freedom itself is a disbenefit to consumers. The Supreme Court upheld the finding of the CAT, which stated that it was not enough for the welfare analysis to be inconclusive, it must demonstrate, and demonstrate clearly, that the interests of consumers would be disadvantaged. In addition, the burden of proving such a finding was not on BT, therefore it had no initial obligation to justify its charges.

Conclusion

The most interesting aspect of this case is the unknown. What if, there was no contractual provision between the parties? Unfortunately, Lord Sumption failed to clarify this point, to which BT argued that there was no ‘third party regulatory restraint’ and that it is only on SMP grounds that Ofcom may disallow charges which a party has the contractual power to impose.[7]

The four MNO’s will now be subjected to the new charging regime of BT, who to date are foreseen as a seemingly unstoppable force. Not even a remit of ‘fair and reasonable’ can dampen BT’s right to pursue aggressive charges which are no doubt going to be borne by the consumer, either in upfront bills or through other ancillary charges MNO’s use to recoup such an increase in cost.

Whilst it is true that BT must comply with the objectives of the regulatory environment in which it operates, a word of caution should be heeded by Ofcom and appealing MNO’s – If such an institution is to challenge an interconnection agreement, it better come with an arsenal of legal weapons at its disposal. Unfortunately, even with artillery, the legal test is essentially a market orientated and permissive approach; therefore to challenge a contractual right on this basis is going to be no easy feat in the future.

To view the judgement read by Lord Sumption go to: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CPtFQliWgR0

[1] Telefonica O2 UK Ltd & Ors v British Telecommunications Plc & Anor [2012] EWCA Civ 1002[2012] EWCA Civ 1002, found at: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2012/1002.html

[2] [Paragraph 3]

[6] Found at; http://blog.justcite.com/case-digest-british-telecommunications-plc-v-telefonica-o2-ltd-and-others

[7] [Paragraphs 47 and 48]