- Why the FARC peace deal does not mean the end of conflict for Colombia & what displaced communities would recommend for future humanitarian work…

By Becky Murphy & The Linking Preparedness Response and Resilience (LPRR) project

Kings College London is leading a piece of research under the START DEPP LPRR project exploring crises survivors and first responders’ recommendations for improved humanitarian programming for community resilience building.

On the 25th August, 2016 the president of Colombia announced a peace deal had been agreed with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia guerrilla group (FARC). Tackling the 50 years of conflict, this news has been illustrated throughout the international media as a huge step towards a more peaceful Colombia and portrayed as the beginning of a new era for Colombia. However, on the 2nd of November 2016 the people of Colombia voted ‘No’ to the Peace deal. The president promises not give up on his hopes of peace and that negotiations will continue.

In September 2016, the LPRR team headed out to a rural area of Colombia under FARC control to hear from displaced community survivors living in humanitarian peace zones what they think and feel about the ongoing peace negotiation. The team headed deep into the Colombian jungle to Cacarica, a village located in the department of Choco, 10km from the Panama boarder. For the community members of Cacarica, the FARC peace talks bring uncertainty, fear and an increased risk of violence.

The LPRR project asks why? Surely peace negotiations are a positive thing, so why are the community survivors so afraid of what will happen next? Here, we ask 5 crucial questions.

1. Cacarica: the crises 1997 – today what has happened?

Between 24 and 27 February 1997, under “Operación Génesis”, a military operation was undertaken in the North-West of Colombia officially intended to attack and capture members of the FARC. In the development of these operations there were killings, torture, disappearances and forced displacement of the Afro-Colombian civilian population, including the brutal murder of civilian Marino Lopez Mena.

Around 3,500 people were displaced and, of these, approximately 2,300 settled provisionally in the municipality of Turbo and in Bocas del Atrato (both in the department of Antioquia), around 200 people crossed the border into Panama, and the others went to different parts of Colombia (IACHR, 2013). 83 were killed or disappeared (Peace Brigades International, 2010).

2. Why did this happen?

According to various investigations the massive displacement that occurred during Operation Genesis has directly benefited large palm cultivator businesses in this region and the involvement of the government, military and paramilitary in these atrocities has been central to Christian Aid’s human rights advocacy work.

In August 2012, General Rito Alejo del Río was sentenced to 25 years in prison for his role in the violent displacements and forming a “macabre alliance” with illegal paramilitary death squad. In July 2013, a total of 16 businessmen were each sentenced to over ten years in jail for crimes of conspiracy, forced displacement, and the invasion of ecologically important land through the removal of the communities of the nearby collective territory of Curvaradó and Jiguamiandó, in Chocó. (El Tiempo, 2013).

In December 2013, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) ruled that the Colombian State was responsible for the forced displacement of the communities of Cacarica in Chocó and obliged to ensure proper reparation.

3. What has Christian Aid done?

Christian Aid Colombia has been supporting its local partners, Inter-church Commission on Justice and Peace (CIJP) and Peace Brigades International to engage in protection and advocacy on human rights and land issues of forcibly displaced people.

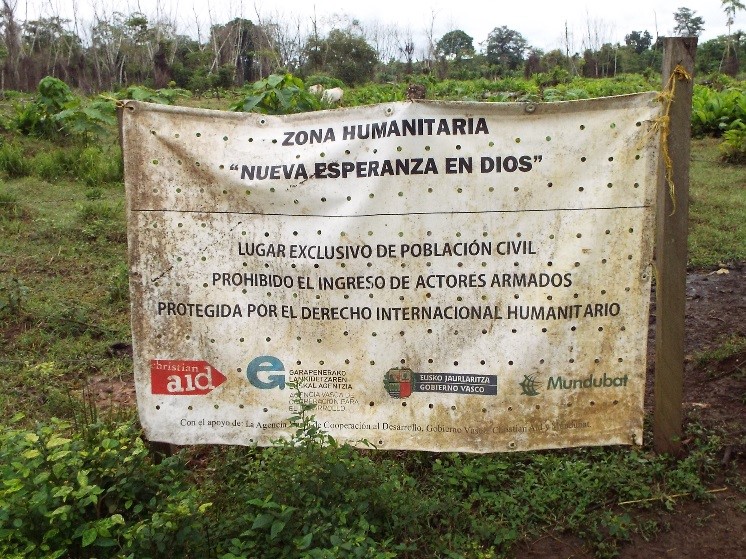

This particular intervention, sought to accompany communities in the Cacarica River valley (Chocó) to inform them about their rights and take their cases to national courts and to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR). This has led to international acknowledgement of humanitarian zones, where returnee community survivors can live and feel safe.

Despite the IACHR ruling being a notable step forward in obtaining justice for survivors, those who have returned to the region report continued threats and harassment by paramilitaries (Peace Brigades International, 2010).

4. Why are the community survivors so scared of the peace talks?

The residents of Cacarica explained that there are three overarching reasons that they fear the peace talks and what will happen next.

- The FARC have respected the peace zones. Not many other armed groups do.

Since returning to their land and establishing their humanitarian peace zone principles, the FARC have respected the peace zones, the communities’ request for civilian rights and to be kept out of the conflict.

- The FARC are not the only groups responsible for crimes

The FARC are by no means the only threat to the community. Several other dangerous rebel groups, paramilitary and private corporations have interest in their land. Since the ceasefire was agreed, the community survivors have seen the paramilitary and other rebel groups coming closer and closer to their humanitarian peace zones.

Through their presence in the area, the FARC have kept other rebel groups, the paramilitary and private corporations away from their land. Therefore, the FARC have created a certain level of stability to the community’s peace and security.

- The community fear the international community will walk away.

Lastly, the community survivors fear that the international community will presume peace with the FARC means peace in Colombia. The survivors are very frightened that the international community will walk away from the people of Colombia when much more needs to be done and the situation may become even more fragile for those living along the Cacarica river basin. Many more actors beyond the FARC need to be involved in peace negotiations, demobilised, disarmed and reintegrated before Colombia has peace and these communities are safe to build a resilient future.

What advice do humanitarian field staff and the community survivors have for the international humanitarian aid sector and others living at risk?

- Communities must organise and unite

- Donors must enable flexible funding

- Community survivors and first responder field staff should conduct ongoing risk assessment sand be empowered to adapt programs according to changing risks

- Train community members to raise awareness, build confidence and develop advocacy skills

- Allow a high level of community ownership and project participation – let the community run the projects.

- Let the women be in charge of the money

- Implement advocacy and protection from the offset.

- Denounce everything.

- Ensure human rights defenders are present in the community with ongoing accompaniment, 24 hours, 7 days a week

- Connect to the national and international domain, media and courts of law. Raise awareness.

The need for peace…

The conflict in Colombia over the past fifty years has led to a quarter of a million people being killed and, alongside South Sudan is home to the world’s largest population of internally displaced peoples.

The survivors of the displacement urge the government to take responsibility and international organisations be there to support and protect them in times of change.

The survivors explain that more than anything they want peace. They feel they cannot truly build resilience nor recover from the atrocities that they have faced until peace has been established and safe access to their land achieved.

However, whilst an important step in the right direction, peace with the FARC does not mean peace for Colombia nor Cacarica. With the Colombian people’s ‘no’ vote and the ongoing negotiations more support is needed to support the protection of the humanitarian peace zones in this volatile period of transition.

The survivors ask the world not to leave them or give up on them.