by Yuchen Zhang, MA in Comparative Literature 2021/22

This blogpost offers a glimpse into a seminar of the MA module 7ABA0016 Queer Connections: Male-Male Desire and the Classical Past. For more information about this module, please visit: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/abroad/module-options/queer-connections-male-male-desire-and-the-classical-past

Gustav von Aschenbach is an established writer with an established public persona. Well into his fifties, he has dedicated most of his life to disciplined work and rigorous writing, holding himself to impeccable personal and social standards. How is it possible that a character like him should end up, at the close of Thomas Mann’s now canonical novella, collapsed in a hotel chair, his head sunken upon his breast, his writing materials cast aside? Feverish, delusional, and scandalously, fatally obsessed with a boy, he watches the perfect form of the youth even with his final breath.

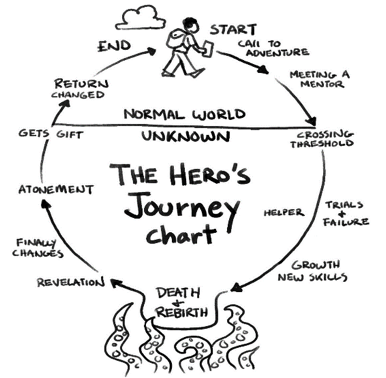

Exploring the connections between death, creativity, and homoeroticism in Mann’s beautifully controlled yet ultimately self-destructive narrative, our seminar in the MA module Queer Connections: Male-Male Desire and the Classical Past recontextualised Death in Venice in the history of European homoerotic literature. By drawing comparisons through time, we found fresh insights into the protagonist’s transformation from self-restrained writer to near-deranged lover, and how his journey, intended to cure a creative block, ended up leading him to the heart of cholera-ridden Venice.

Controlled suffering has, since classical times, been valorised as a masculine ideal in literature and in visual art. Winckelmann memorably described the essence of Greek male beauty as a “tranquil grandeur,” or calmness despite the raging turmoil beneath. Aschenbach’s own ideal of male perfection is symbolised in Death in Venice by the figure of Saint Sebastian (depicted below by Botticelli). Bound and penetrated with arrows, yet poised in elegant, passive martyrdom, Saint Sebastian embodies the noble restraint that forms one half of an important duality: the Apollonian, in Nietzsche’s view on classical Greek literature and culture, means restraint, order, and form, while the Dionysian entails passion, chaos, and formlessness. In Death in Venice, we can see Aschenbach—a modern Saint Sebastian of the writerly profession—transitioning from one extreme to the other.

In Nietzsche’s explanation of the Apollonian-Dionysian dynamic in his The Birth of Tragedy, he describes how art emerges from a careful balancing of the two. Art gives form (the Apollonian) to chaos (the Dionysian) and provided the Greeks with a way of dealing with the abyss of life. What Death in Venice shows is not balance, however, but the mesmerising yet deadly consequences of extremity.

By studying Mann’s modern text through this lens, the development of Aschenbach emerges as a loss of self-control, with fatal consequences. On his way into Venice, he encounters a stranger whose extravagant clothing and makeup clash grotesquely with his age, an effect cast into relief by the youthful company he keeps, and Aschenbach responds to it with revulsion. Yet towards the end of the book, Aschenbach himself dons makeup in a love-sick state, hoping to mask his age and attract the attention of his beloved boy. As passion takes hold, Aschenbach neglects first his writing, then his ideal of masculine dignity, and his reputation. He undergoes a sort of degeneration, mental and physical health declining until, beckoned by a hallucination of love, he meets his demise.

The journey from Aschenbach’s solid life on Munich’s firm ground into the watery archipelago of Venice is itself a journey into dangerous fluidity, and in that formlessness Aschenbach’s fate lies waiting: the idea of travelling first strikes Aschenbach as an imagined vision of a humid, tropical land and the language used to describe this mental image overlaps significantly with Mann’s later characterisation of cholera as a disease that emerged from the swamplands. Bringing Aschenbach’s journey—and his life—to rest in Venice, the city of water, Death in Venice betrays wider anxieties about the slipperiness and slipping away of control, about fluidity and exchange of fluids, and about desire and formlessness that ripple through from classical Greece into the twentieth century.

I am a third-year Liberal Arts student from London, majoring in Comparative Literature and minoring in Classics. My academic interests centre on the spread of syncretic transnational social and cultural forms, most recently including anti-colonial and black liberationist movements and the development of Ethio-Jazz and UK Grime. Whilst in sixth form I won the Mary Turner award, given to female students for their academic achievements and contributions to the wider school community. For my dissertation, I am analysing 20th c. Anglophone Caribbean authors’ use of Classical Graeco-Roman texts in order to reframe their post-colonial identities. I am particularly interested in the use of English within the colonial project as a culturally destructive tool and the feelings of rupture that this has engendered. I also teach as a part-time Swimming and Lifesaving instructor and wish to continue working with children in developmental settings in the future.

I am a third-year Liberal Arts student from London, majoring in Comparative Literature and minoring in Classics. My academic interests centre on the spread of syncretic transnational social and cultural forms, most recently including anti-colonial and black liberationist movements and the development of Ethio-Jazz and UK Grime. Whilst in sixth form I won the Mary Turner award, given to female students for their academic achievements and contributions to the wider school community. For my dissertation, I am analysing 20th c. Anglophone Caribbean authors’ use of Classical Graeco-Roman texts in order to reframe their post-colonial identities. I am particularly interested in the use of English within the colonial project as a culturally destructive tool and the feelings of rupture that this has engendered. I also teach as a part-time Swimming and Lifesaving instructor and wish to continue working with children in developmental settings in the future.  Tonje Beisland is a Norwegian third-year Liberal Arts student majoring in Comparative Literature and minoring in English literature. She is the sub-editor of the independent online publication NUET which offers a wide range of topics centred on self-expression, art and sustainability. She received ‘Garborgprisen’ and the first prize in the Humanities section of ‘Young Scientists’ hosted by the Research Council of Norway for her research on feminism, intersectionality and patriarchy. After starting her BA at King’s College London, her most recent interests have extended to the postcolonial and transnational context of the Caribbean. She is currently working on the application of Greek and Norse mythology in contemporary Caribbean and Norwegian literature for her dissertation and intends to enter the publishing industry after graduating.

Tonje Beisland is a Norwegian third-year Liberal Arts student majoring in Comparative Literature and minoring in English literature. She is the sub-editor of the independent online publication NUET which offers a wide range of topics centred on self-expression, art and sustainability. She received ‘Garborgprisen’ and the first prize in the Humanities section of ‘Young Scientists’ hosted by the Research Council of Norway for her research on feminism, intersectionality and patriarchy. After starting her BA at King’s College London, her most recent interests have extended to the postcolonial and transnational context of the Caribbean. She is currently working on the application of Greek and Norse mythology in contemporary Caribbean and Norwegian literature for her dissertation and intends to enter the publishing industry after graduating.