James Fuller is a Peer Researcher, Expert by Experience and a Support Worker at a Day Centre for people who are homeless in London. (1,200 words)

Brighton and Hove Safeguarding Adults Board recently published the key messages arising from a review. A Safeguarding Adults Review is held when an adult in the local authority areas dies as a result of abuse or neglect. In this case, the adult was sleeping rough and had been identified as ‘difficult to engage’. Chris Scanlon and John Adlam have written extensively about Diogenes, homelessness and what to do about people whose refusal to be included remains a problem for themselves and society as a whole. This review brought into sharp focus some of these same issues. Namely how can we safeguard Diogenes? According to the essayist Plutarch, the philosopher Diogenes the Cynic (412-323BC) lived in a barrel in Corinth and spent his time pouring vitriol on his fellow beings, who he roundly despised. One day, Alexander the Great invited Diogenes to a gathering, but the drum-dweller declined. Instead of having Diogenes executed, the usual outcome for disrespecting world conquerors, Alexander went down to see him. Having greeted Diogenes, Alexander asked him if he wanted anything. Diogenes replied: “Yes, stand a little out of my sunshine” (Plutarch, Alexander, 14 Cf.).

If, as a civilised society, we have a moral duty towards all mankind without fear or favour, how far does that burden extend in face of such dogged resistance? Or, is our proper duty to respect another person’s right to live as they wish, even to the point of killing themselves, slowly perhaps through substance abuse and/or self-neglect, or by a single act of suicide? If this is their choice, is it not also their responsibility, or should we, by default, not only take on the emotional burden, but also contribute to their demise by funding such a lifestyle, either as individuals, or through state subsidy?

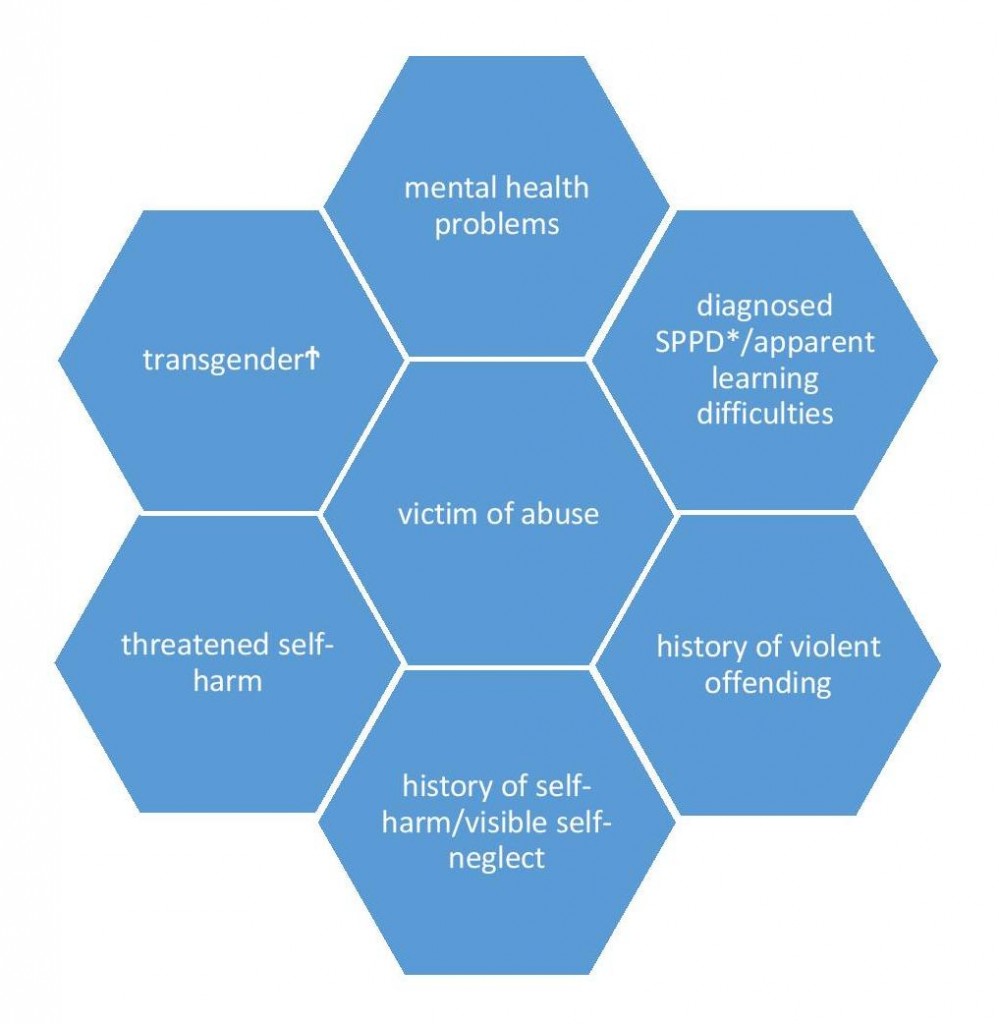

The purpose of safeguarding is to ensure that multi-agency professionals working with at risk adults do so in a coherent and coordinated manner, acting under a set of issue-specific policies and procedures, in order to achieve optimal outcomes. Although there is much rhetoric about the importance of working together holistically, this review brings into sharp focus how challenging this can be. To use the analogy of ten pin bowling, the bowling ball shown below is segmented by the issues and vulnerabilities presented by the person who was subject of this review…

*Serious Paranoid Personality Disorder

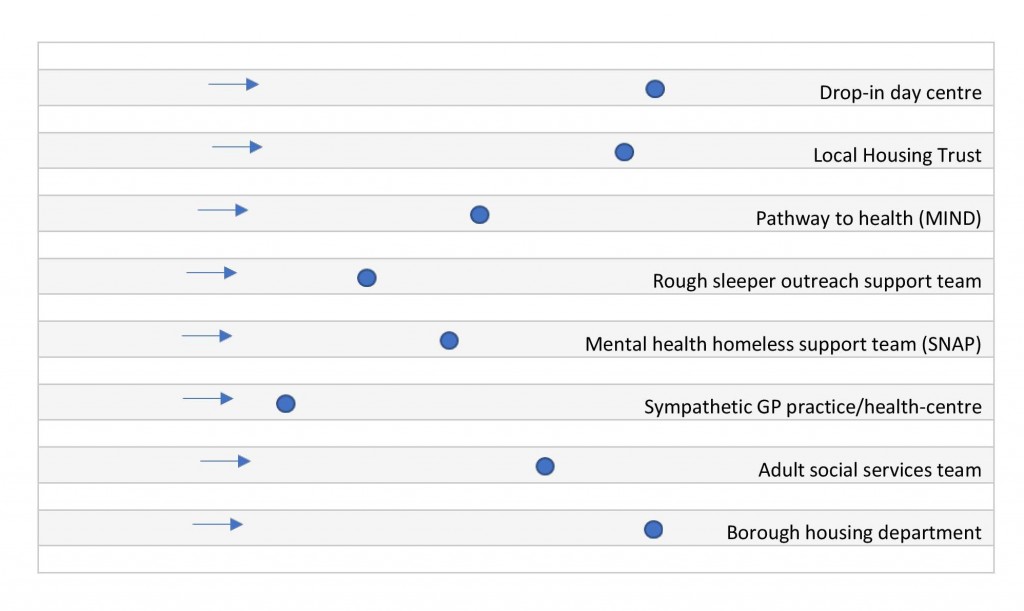

…and here are the lanes down which they are known to have travelled:

The arrows are significant because they highlight that this is a one-way system and like the ball, the subject must be returned or find their way back to the start in order to re-enter the same lane, or be directed down another one. As a front-line practitioner and someone with lived experience of this game, what is of concern is how to provide a coherent safeguarding response across these parallel lines. There are plenty of multi-agency policies and procedures, committees, case conferences and working parties who meet and discuss, but extending these conversations into consistent, combined activity, particularly when human as well as financial resources are scarce, can be exceptionally difficult.

The arrows are significant because they highlight that this is a one-way system and like the ball, the subject must be returned or find their way back to the start in order to re-enter the same lane, or be directed down another one. As a front-line practitioner and someone with lived experience of this game, what is of concern is how to provide a coherent safeguarding response across these parallel lines. There are plenty of multi-agency policies and procedures, committees, case conferences and working parties who meet and discuss, but extending these conversations into consistent, combined activity, particularly when human as well as financial resources are scarce, can be exceptionally difficult.

In the case outlined in the review, there was some coordination between services while the person resided in one county, but none of the accumulated narrative, or care plan was conveyed to their opposite numbers who attempted to engage with the person when they abruptly moved to an adjacent district. There appears to be no suitable network between local authorities through which file data could be passed, or national data-base from which the information might have been extracted – not even the Vulnerable Adult At Risk alert that had been raised in the first location. In any event, without a formal lead agency, who was to have taken on the search?

It is tempting to retort that the service user should have made known their circumstances and were it not for the mental health and learning difficulties, this might be a reasonable hypothesis. Even so, relying on self-reporting, as we must in many cases, often leaves services woefully ill-informed, or deliberately misled. Nonetheless, we are dealing with adults and in an environment replete with data protection, privacy and human rights legislation designed to uphold an individual’s civil liberties. There are lines we cannot cross, even when to do so would patently be in a person’s best interests. Instead, we must rely on our experience, ‘professional curiosity’ and emotional intelligence to build trust and encourage disclosure. This can take time and requires a degree of tolerance and continuity, which, as argued here, are in short supply in the current climate of austerity. Your blogger feels no shame in noting that in this particular review, staff from the charitable sector were singled out for their ‘person centred’ and ‘more flexible’ approach.

Despite the challenges inherent in the system, it is also the case that achieving meaningful engagement when mental health or psychoses are present is difficult, not least because by the time people are sleeping rough, they are often ‘self-medicating’, rarely taking their prescribed drugs and living in fear of being ‘sectioned’. In the case under review, it was acknowledged that this ‘was a difficult and potentially dangerous tenant to accommodate’. Specialist supported housing providers strive for maximum inclusion, but even they must routinely screen out applicants with a history of arson, or who are likely to be violent towards other residents or staff.

Tragically, this person deteriorated rapidly and exhibited such chronic self-neglect that local residents near the caravan where she was living sought to have her removed. The mental health team were alerted to her worsening condition, but following a rapid assessment concluded (once again) that she had capacity. This decision did not reduce the serious concerns that surrounded them, but soon afterwards she was found dead. A tube had been connected to a gas canister outside the caravan and run into her sleeping bag.

The coroner’s verdict was ‘misadventure to which self-neglect contributed’. No blame was laid at any agency’s door. That is surely right. Even so, the Safeguarding Adult Review that followed concluded that a failure to invoke prescribed safeguarding procedures robustly meant that ‘an integrated and coordinated multi-agency partnership led approach was not achieved’. There is a line tucked away in the review’s concluding remarks which struck a cord. We may not be able to solve Diogenes problems through our concerted offer of help and support, but respecting and listening to them is key:

“The determined focus on reconnecting [the person] with [their] local area, whilst understandable as it offered [them] the best chance of being housed, was done in such a way that risked [them] feeling unheard”.

James Fuller is a Peer Researcher, Expert by Experience and a Support Worker at a Day Centre for people who are homeless in London.

References

Brighton and Hove Safeguarding Adults Board: Safeguarding Adults Review Professionals Briefing (March 2017).

Scanlon, C and Adlam, J. (2008) Refusal, social exclusion and the cycle of rejection: A cynical analysis? Critical Social Policy 28(4) 529-449.