Yes! It’s here! It’s out!

Greenfoot 2.0 has just been released. After a lot of hard work, and about a month behind schedule, we finally completed the work on Greenfoot 2.0. Even though it may not be immediately obvious, this is one of the largest updates we have ever produced for Greenfoot. A lot of work has been done internally, and users will discover the effects of many of them over time.

The Greenfoot 2.0 splash screen

New features are available in the editor, for processing and recording sound, for editing images, debugging your programs, and more. Here, I will summarise the most interesting changes (at least those that users can directly see – there are many internal improvements to performance and stability that I won’t discuss here).

The first thing users will notice after upgrading is a new splash screen. (Yes, we are now supported by the good folks at Oracle, instead of Sun Microsystems, after Sun was swallowed up by Oracle.)

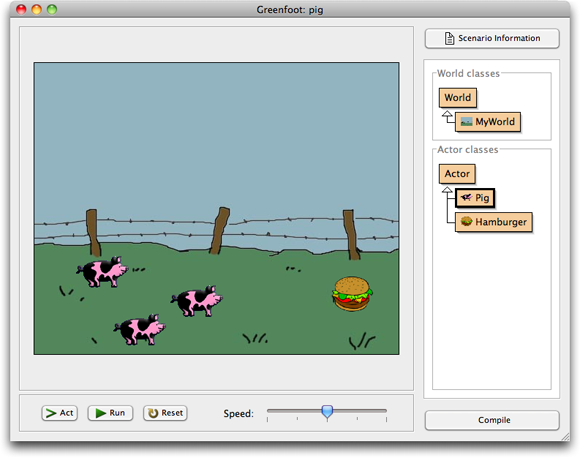

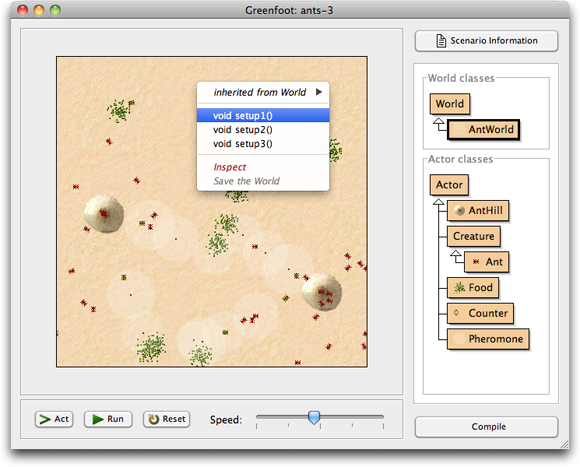

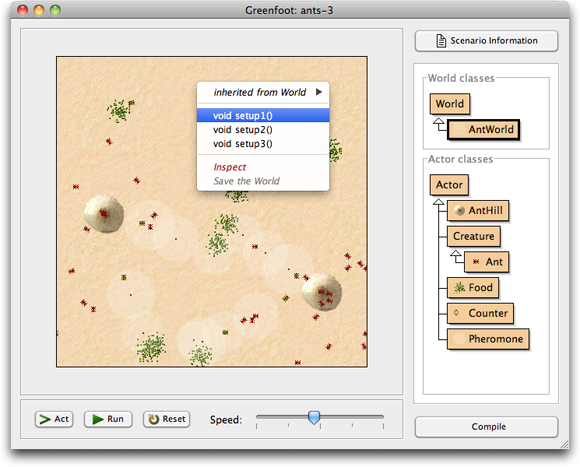

But after that, it all might look rather underwhelming at first. The Greenfoot main window looks pretty much as it used to look before. “Where’s the new stuff?”, I hear you ask. Sharp-eyed users may notice one small change: the world name, that used to be shown above the world in the main window, is not there anymore.

The name of the world used to serve as a placeholder to represent the world object itself. It had a right-click functionality, that let you access the world object’s context menu to invoke instance methods on the world object itself. The problem was that this functionality was quite hidden, and many users never discovered it. It was bad UI design, since nothing in the name indicated that this was clickable. It had, in fact, almost easter egg-like quality.

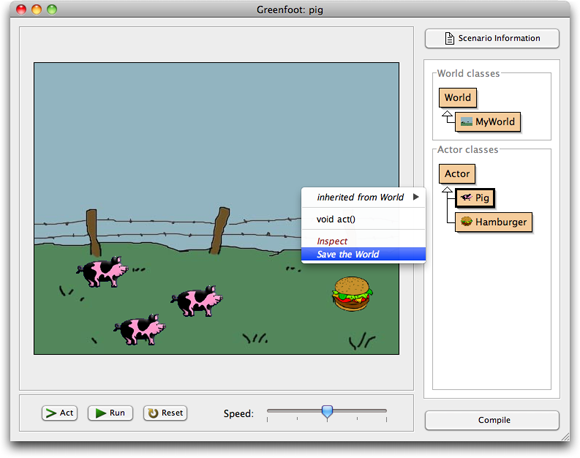

We have now removed this name, and instead made the whole world area right-clickable. Right-clicking the world itself (or indeed the grey background behind it) will show the world object context menu and lets you invoke the world methods.

The main window

Right-clicking in the world itself is more natural (more conforming to user expectations and more discoverable) and we expect that users will find this menu more easily now. (By the way, the reason that this was not done like this in the first place is that early versions of Greenfoot had different functionality attached to mouse clicks in the world.)

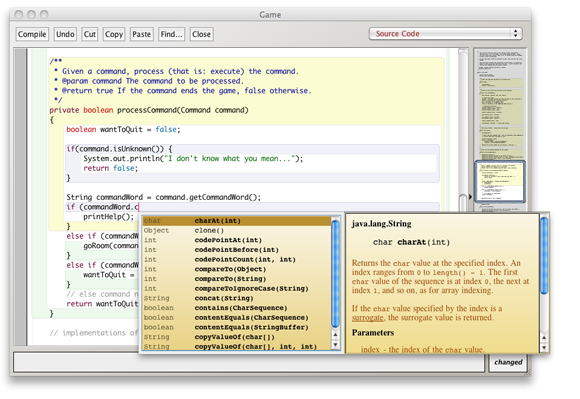

The next thing many users will discover is the new look of the editor.

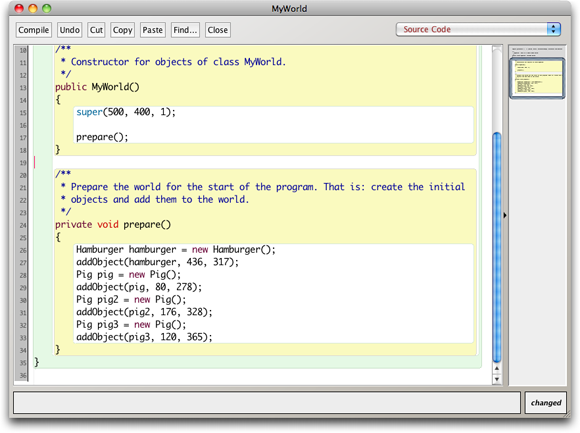

The new editor

Greenfoot now incorporates the same editor that is used in BlueJ since the BlueJ 3.0 release earlier this year. The new features include scope highlighting, a new navigation view, better Find and Replace and code completion. (Code completion is activated by pressing Ctrl-Space.) I have described these features in more detail in an earlier blog post, when they came out with BlueJ – read them there if you want to know more..

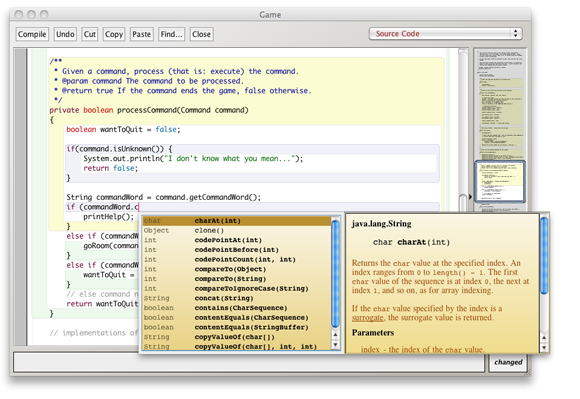

The new Greenfoot editor

We expect that the new editor, especially the availability of code completion for Greenfoot API calls, will be a substantial improvement to the user experience. (I have been using it for a few months now, and I wouldn’t want to work without it anymore!)

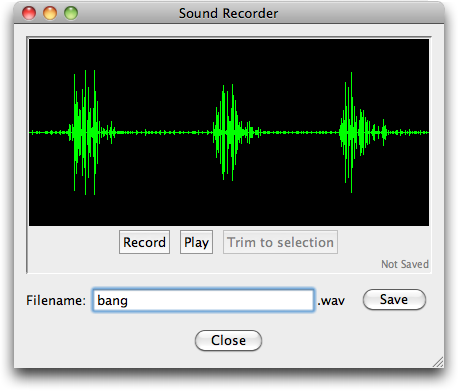

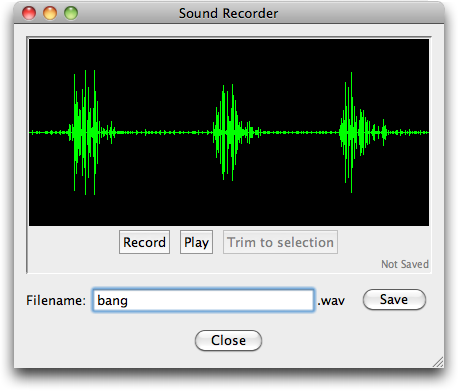

Sound recording

The sound recorder

Greenfoot now has a built-in sound recorder. It can be found in the Controls menu, and you can now record your sounds directly from within Greenfoot. The functionality is very simple — just recording and trimming is supported — but this is what you need most of the time. If you want more sophisticated sound editing, you can still use third party applications (such as Audacity). However, the built-in recorder should be sufficient in many cases.

There is unfortunately a Java bug that cases problems with sound recording on some USB connected microphones. It works, however, with most microphones, and we hope that the remaining problems will be fixed in a future Java update.

But sound recording is not all that’s new with sound. You now also have more control over sound playback.

MP3 support

Yes, mp3 support! Greenfoot can now play mp3 files! Really. So go on and write your first MP3 player.

The GreenfootSound class

In previous Greenfoot versions, programmers had little control over how sounds are played. They could be started, but that’s all. Now, Greenfoot has a new class called GreenfootSound. It has method for starting, stopping and pausing sounds, as well as looping. This makes working with sounds much more flexible.

For short, simple sounds (such as sound effects), the Greenfoot.playSound(…) method is still the best to be used. But if you need more sophisticated functionality, create a GreenfootSound object and you can control the sound in more detail.

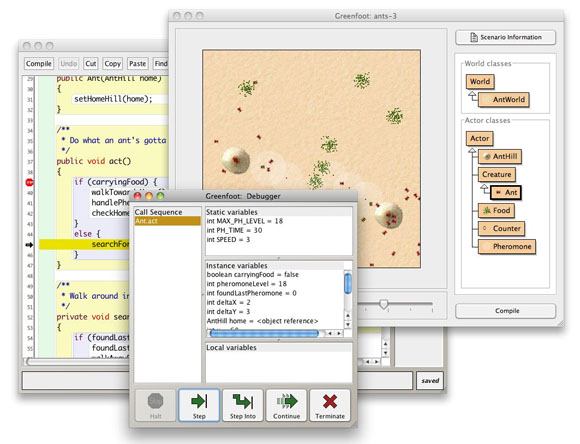

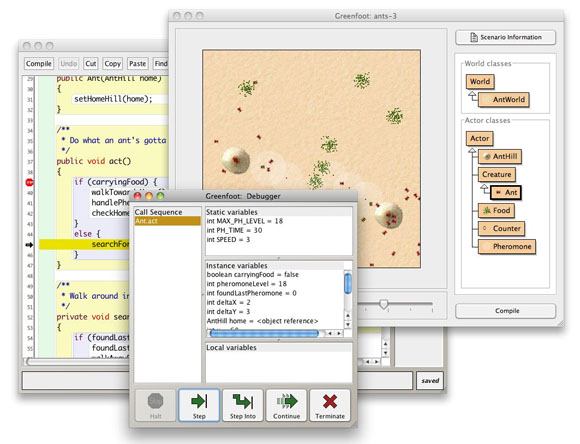

The debugger

Greenfoot now has a debugger built in. As some of you had discovered before, the code for the debugger has been there under the hood for some time (and there were ways to make it come up), but it was not working well, not supported, not finished, and had no proper interface.

The Greenfoot debugger

Now you can open the debugger window from the menu, set breakpoints, stop the execution, single step through your programs and monitor your variable values. Especially for illustrating the working of control structures, this should be a useful help.

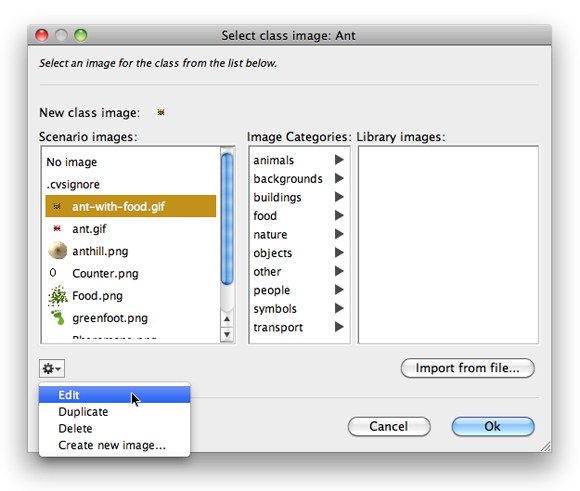

Image editing

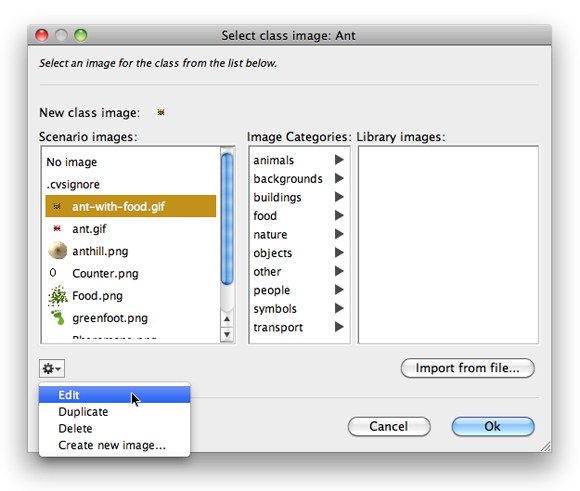

Creating or editing images is a task that is very often part of developing Greenfoot scenarios. Now you can start creating or editing images directly from within the Greenfoot image dialogue.

Editing images

The action menu under the image list offers functions to edit, delete or create an image. This will happen in external applications. By default, Greenfoot will open the default application for the chosen file type on any platform. This behaviour can also be configured to select a specific application. (I will write in more detail about some of these new functions in separate posts soon – I’ll discuss how to do this then.)

When images are created, they are automatically placed into the scenario’s images folder, so that they are immediately available for use in Greenfoot.

Unbounded worlds

The last bit of functionality I’ll talk about today are unbounded worlds.

As you know (if you have used Greenfoot in the past), actors cannot leave the world. When they try to move beyond world boundaries they are simply placed at the edge of the world. Breaking out is impossible for them. This has good reason: if actors were to leave the visible world, it can be very hard to get them back. You cannot interact with them anymore, and you don’t really know where they are. In fact, you may not even be aware that they are still there. This has great potential of confusion and difficulty for beginners.

This behaviour remains the default in Greenfoot 2.0 — but you can now configure your world to allow actors to leave the visible area for specific scenarios, should you want to do that. (And we know that some of you do: many of you have asked for this for some time!)

The world is then essentially infinite in all directions, and the visible world in the Greenfoot window is just a viewport into a small part of this eternal universe.

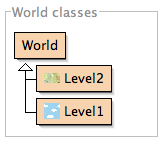

The World superclass now has a second constructor that allows the bounds to be removed:

| Constructor Summary |

World(int worldWidth, int worldHeight, int cellSize)

Construct a new world. |

World(int worldWidth, int worldHeight, int cellSize, boolean bounded)

Construct a new world. |

The first constructor is as before. Thus, you old code will work unchanged. For example, a world constructor

public AntWorld()

{

super(500, 400, 1);

}

will work as before and create the usual bounded world. However, you can now also use

public AntWorld()

{

super(500, 400, 1, false);

}

In this case, actors will be allowed to leave the visible world and walk as far away as they like. For some type of games this will be very useful. When out of the visible world, they will still act, cause collisions, etc. You just cannot see them.

And so…

So, plenty of new stuff in Greenfoot 2. The last thing to tell you is where to get it. And that is, of course, where it has always been: www.greenfoot.org.

Install it, take it for a spin, and let us know what you think. We’d love to get your feedback. Bug reports, of course, but also things you like. You comments are one of the inputs that drive our future development.

And most of all, as always: Have fun programming!

Update:

I forgot to mention one new feature: Saving the world. I have now described this in a separate blog post.