This post is written by and posted on behalf of Tom Mitchell, who undertook an internship in the Foyle Special Collections Library, as part of his MA History course at King’s. The internship ran from January to April 2022.

This post is written by and posted on behalf of Tom Mitchell, who undertook an internship in the Foyle Special Collections Library, as part of his MA History course at King’s. The internship ran from January to April 2022.

An introduction to the project

A country is much in the same boat as a shop. A visitor searches for something to represent its shop window; to tell him what its inhabitants are like, what is their attitude to life[?]…How easier to discover these secrets than by a study of the country’s newspapers and magazines! There, in cold print, lies the whole story.

These words from the editor’s foreword to the 1958 edition of the West African annual neatly encapsulate this year’s history internship project at the Foyle Special Collections Library. The West African annual is one of around 350 rare periodicals from the historical library collection of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, which was transferred from the government department’s longstanding library to King’s College London in 2007. It is fitting then, that this collection should be studied now, to uncover ‘hidden’ voices of the colonies where the periodicals were produced. My project uses these sources to explore themes of empire and colonialism, seeking African opinions on the colonial policy of development in the 1950s.

‘Development’ was a term used for the European policy of spending tax revenue on the provision of loans and grants to fund projects in what were considered ‘under-developed’ colonies. The aim of this policy was ostensibly to improve living standards, providing for schools, hospitals, and infrastructure among other things although, similarly to other imperial policies, purported altruism often masked self-interested motivations such as development’s role in post-war reconstruction and as a platitude to quieten calls for decolonisation. First introduced under Joseph Chamberlain’s Colonial Office at the turn of the 20th century, significant sums were not allocated to British development projects until the interwar years. However, the most dramatic increase in funds was approved during the Second World War in conjunction with an apparent shift in the policy’s focus towards ‘welfare’ and preparing colonies for independence.

Voices and perspectives in the material

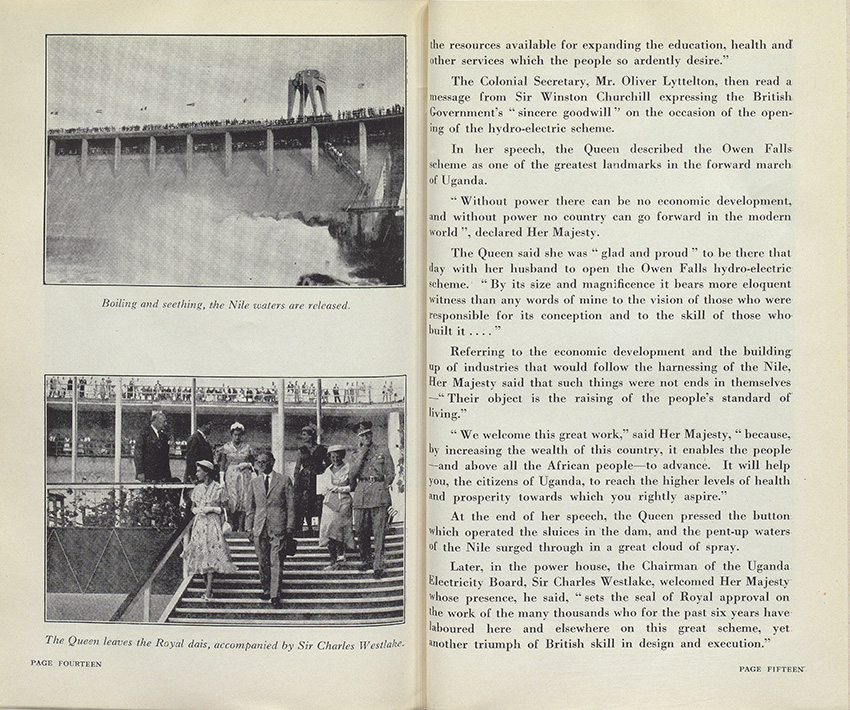

If the periodicals in the FCDO historical collection are shop windows into the African countries, through which attitudes towards development can be seen, the central display in all of them highlights their contemporary position as colonies subject to continued British rule. Although many of the periodicals were aimed at a mostly (though not exclusively) African audience, the dominance of British perspectives is plain. For example, the report from the Uganda review on the opening of the Owen Falls Dam (a flagship development project), quotes British sources. No Ugandan views are represented.

Nonetheless, through persistent research, occasional representations of African voices can be traced, albeit with varying degrees of credibility. A particularly rich extract from an earlier issue of Uganda review portrays an evolution of responses to development in Uganda:

Many parents refused to send their children to school. New crops like cotton and coffee were unpopular. Chiefs and Government officers had persistently to urge the people to plant these crops. Now things are greatly changed. People often complain that the coffee seedlings and cotton seed issued to them are not sufficient. Everywhere the people want more schools and more dispensaries. In short, the people are now eager for improvements in their standards of living.

In short, initial reluctance was replaced with enthusiasm as the fruits of development became clear. The suggestion of willing and even eager acceptance of British direction and development must, of course, be read with some caution. In this case and in others within the periodical, a positive attitude towards development has been imposed upon Ugandans who could not exercise their own voices directly on the same pages. As the project progressed, further research illuminated the validity of this view, or at least the degree to which it represented popular opinion within or across the colonies. Conclusions are to be published in the online exhibition referred to below.

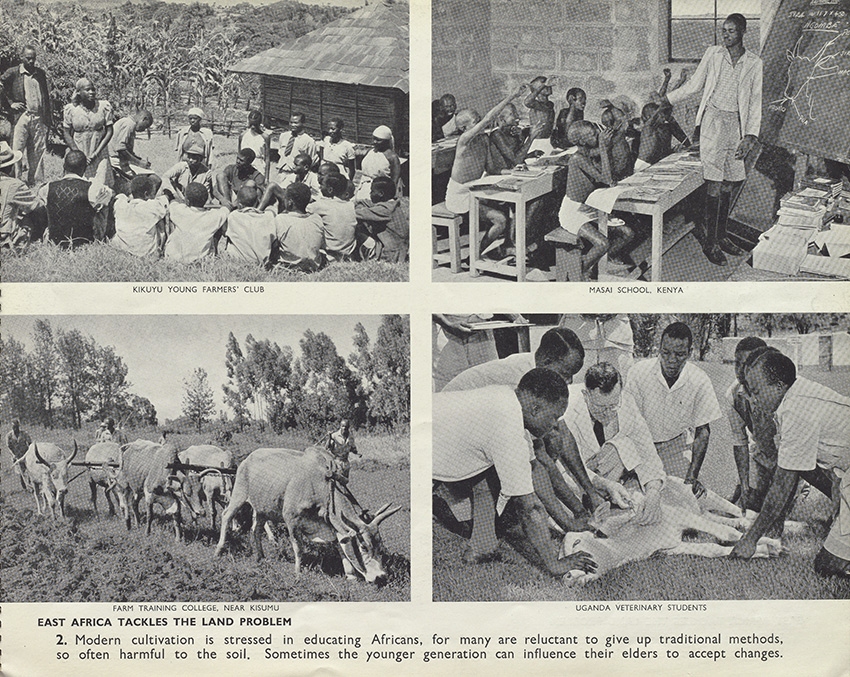

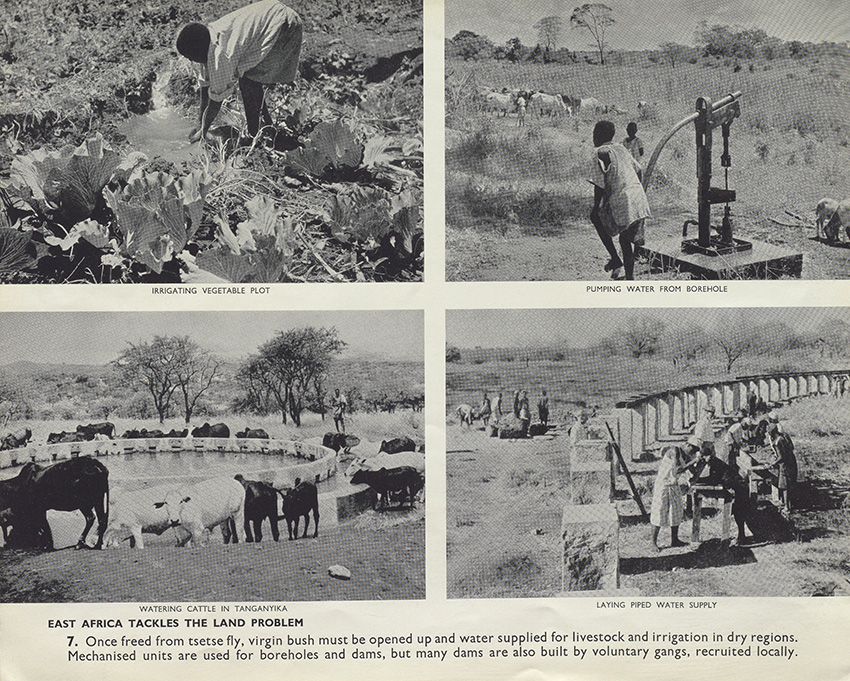

The other view represented by this quotation – a reluctance to engage in unfamiliar British practices is, at this stage, more supportable. The theme of younger people convincing their parents of the benefits of development is recurrent in Uganda review and in educational materials produced by the Central Office of Information in London. Likewise, nostalgia for traditional practices is encapsulated in paraphrased notions that: ‘All that a man had to do was cultivate his piece of land…why not just let things remain as they were?’. The idea that Ugandans were apathetic or annoyed at development may additionally be read into the very existence of so many pieces in the periodicals designed to inform them of project progress. The colonial administrators and periodical editors clearly thought this propaganda necessary, and these attitudes are a likely explanation as to why.

If you ask me …

A final African attitude towards development discernible from the periodicals is scepticism around Britain’s self-proclaimed altruistic motivations for development projects. Somewhat ironically, although perhaps unsurprisingly, this scepticism is more clearly detectable in a periodical aimed at a British audience than those aimed at African people. “If you ask me …“ was a Colonial Office periodical which provided sample answers to questions which it was thought may be posed to colonial administrators, often submitted by readers who had been faced with the same enquiries. A small number of questions notably support the historical theory that post-war development was primarily a means to exploit natural resource-rich colonies such as Nigeria and the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana) in order to bridge the so-called ‘dollar gap’ resulting from the enormous debt Britain owed to the United States. For example:

Is it true that the colonies are making up Britain’s dollar deficit instead of using all their dollar earnings for their own needs?

Of what benefit to my country is the Sterling Area? Now that we are approaching self-government, would it not be better for us to be independent from the financial aspect as well?

To my mind ‘development’ means spending money, yet in my country which badly needs development, we are always being called on to save money. Why is this?

Combining my interest in development and wider academic debates on representations of the colonial experience, my research project sought indigenous African reactions to development, such as those discussed here. They ranged between the positive and the critical; and many were also highly nuanced, such as in the last example which expresses a healthy scepticism, while openly referring to development’s necessity as if it were an uncontroversial statement. The results of my study will soon be published in the form of an online exhibition which will be available to view here. I also gave a talk to Libraries and Collections staff at King’s about my research.

Bibliography

Principal sources cited:

Great Britain. Central Office of Information. East Africa tackles the land problem: set of 12 plates. London: Central Office of Information, 1953 [FCDO Historical Collection OVERSIZE D11 GRE]

“If you ask me…” London: Colonial Office, 1952-65 [FCDO Historical Collection Periodicals]

Uganda review. Entebbe: printed by the Government Printer, 1950-55 [FCDO Historical Collection Periodicals]

West African annual. Zaria, Nigeria: Gaskiya Corporation, 1949-1960 [FCDO Historical Collection Periodicals]

Secondary reading:

Michael Havinden and David Meredith, Colonialism and development: Britain and its tropical colonies, 1850-1960 (London: Routledge, 1993)

Dorothy L Hodgson, ‘Taking stock: state control, ethnic identity and pastoralist development in Tanganyika, 1948-1958’, Journal of African history, 41 (2001), 55-78

Gerold Krozewski, ‘Sterling, the “minor” territories, and the end of formal empire, 1939-1958’, Economic history review, XLVI (1993), 239-65

Sarah Stockwell, The business of decolonization: British business strategies in the Gold Coast (Oxford: OUP, 2000)

NJ White, ‘Reconstructing Europe through rejuvenating empire: the British, French, and Dutch experiences compared’, Past and present, 210 (2011), 211-36

Really interesting to read about your research, and I look forward to the talk and exhibition.

Hi Dawn. Many thanks for you comment, and for reading. I will forward it to Tom and make a note to update you. Best wishes, Adam

A refreshingly critical glimpse into British overseas ‘development’ in Africa post-war and the decline of Empire. I look forward to the exhibition.

Hi Belinda. Thank you for your thoughtful comment on Tom’s work. We hope you’ll enjoy the talk and the online exhibition, when it is published. Best wishes, Adam