This post is written by Jack Gleeson, Special Collections Assistant, who is currently working on the Eric Mottram collection.

Presented to King’s College by his siblings in 1996, and now held in the Foyle Special Collections Library, the library of Professor Eric Mottram (1924-95) is a wide-ranging and varied collection, reflective of an academic with diverse tastes and scholarly interests.

Professor Mottram spent much of his life teaching both English Literature and American Studies, lecturing in numerous places throughout the United States and the world, and holding the position of Professor of English and American Literature at King’s from 1982 to 1990. As a result, a significant portion of his extensive collection is devoted to American novels and poetry, and, in particular, poetry from the Beat scene.

In the 1960s, Mottram met and corresponded with a number of figures in underground literary movements, and at the close of the decade he befriended and spoke with key Beat personage William S Burroughs (1914-97), who was living in London at the time.

In the 1960s, Mottram met and corresponded with a number of figures in underground literary movements, and at the close of the decade he befriended and spoke with key Beat personage William S Burroughs (1914-97), who was living in London at the time.

Burroughs was of particular interest to Mottram, who around this time wrote The algebra of need, one of the first critical works to look at Burroughs’s output up to that point. This piece was initially published in Intrepid magazine’s special Burroughs issue of 1969-70, which was edited by Mottram, and then later as a monograph in 1971.

With this background and context in mind, Mottram naturally amassed a large number of books by Burroughs, and in cataloguing the collection we have so far come across signed copies of his later works Cities of the red night (1981) and The western lands (1987). Most captivating as a piece of literary and social history, however, is a first edition of Burroughs’s first published novel, Junkie (1953).

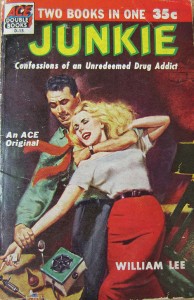

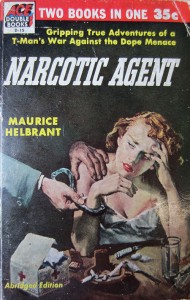

Later retitled Junky by Penguin in 1977, though even today never published under Burroughs’s intended title, Junk, the first edition of Junkie was put onto drugstore shelves under the pseudonym ‘William Lee,’ and was published as an Ace Double Book, bound together with the previous decade’s Narcotic agent by Maurice Helbrant, the ‘gripping true adventures of a T-man’s war against the dope menace’.

Later retitled Junky by Penguin in 1977, though even today never published under Burroughs’s intended title, Junk, the first edition of Junkie was put onto drugstore shelves under the pseudonym ‘William Lee,’ and was published as an Ace Double Book, bound together with the previous decade’s Narcotic agent by Maurice Helbrant, the ‘gripping true adventures of a T-man’s war against the dope menace’.

Chiefly autobiographical in nature, a work entitled Junkie was unsurprisingly full of references to opiate use and drug dealing, not to mention ‘alcohol depression,’ ‘crustacean horror’ and ‘junk sickness’; and additionally delved into pickpocketing, and homosexual relationships between Burroughs and others.

Tethered by the much stricter social mores of the 1950s, Ace Books set to work editing and censoring Burroughs’s manuscript, going so far as to insert a number of editorial notes, intended to protect themselves from legal liability for, or moral association with, the writer’s statements that they did not cut out.

These notes are inset throughout the text to rescue the reader from the world of drugs, asserting that Burroughs’s declarations that ‘Sex is more enjoyable under the influence of weed’ and that ‘Weed is positively not habit-forming’ (p. 33) are ‘contradicted by recognized medical authority’ (p. 34). Solomon and Ace Books likewise distance themselves from Burroughs’s disparaging comments about the United States justice system later in the book.

While a number of Burroughs’s remarks about junk and justice were included but accompanied by disclaimers, references to the author’s homosexuality were removed entirely from this first edition, and entire paragraphs and pages detailing relationships between Burroughs and other men were not seen until Penguin restored the complete manuscript in 1977. Further text, taken from letters written to Allen Ginsberg, was reinstated by scholar Oliver Harris for Penguin’s 2003 edition of Junky.

Carl Solomon, a friend of Allen Ginsberg, and nephew of AA Wyn, the founder of Ace Books, assured the readers in his publisher’s note that the text was published purely with noble intent: to ‘forearm the public’ against the ‘drug menace’ and to ‘discourage imitation.’

This seemingly honourable resolve and the social mores of the period did not however stop the publisher from unleashing the book with a lurid, attention-grabbing image on the cover, along with a vivid subtitle: Confessions of an unredeemed drug addict, both of which seem to capitalise on the plight of individuals suffering from drug addiction, and appear unambiguously aimed at a thrill-seeking reader base. It is worth noting that nothing quite as melodramatic as the scene depicted in the cover illustration actually happens in the novel.

The Junkie of this double books edition is a revealing item: we are now able to look back at the Ace Books censored novel, featured in this article, with the 2003 edition of Junkie in hand, and know exactly what was removed. We can witness the trajectory of Burroughs from the author of a throwaway subway paperback, advertised with the slogan, ‘TWO BOOKS IN ONE – 35c,’ to heavily-studied, hugely influential novelist and writer, whose personal life, far from having entire components cut out of texts by publishers, has been thoroughly exposed and explored through countless biographies and collections of letters.

Both of the eye-catching covers of this double book edition are shown here, courtesy of Penguin Random House.

Special Collections staff continue to sort and catalogue the Eric Mottram collection and are happy to answer enquiries on this or other areas of the collection.

Bibliography and references:

Jed Birmingham, ‘Eric Mottram and The Algebra of Need,’ RealityStudio, [http://realitystudio.org/bibliographic-bunker/my-own-mag/the-my-own-mag-community/eric-mottram-and-the-algebra-of-need/, accessed June 21, 2017]

William S Burroughs, Junkie (New York: Ace Books, 1953)

William S Burroughs, Junky: the definitive text of ‘Junk’ (London: Penguin Books, 2003)

William S Burroughs. Rub out the words: the letters of William S Burroughs, 1959-1974 (London: Penguin Books, 2012)

Maurice Helbrant, Narcotic Agent (New York: Ace Books, 1953)

Barry Miles, William S Burroughs: a life (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2015), 491