Why are donors so reluctant to fund protracted, slow onset, urban crises?

By Becky Murphy (Resilience Capacity Building Officer and Lead Researcher at Christian Aid and Kings College London University)

Becky is currently travelling to 8 humanitarian intervention sites to capture if and how emergency response can integrate resilience building.

“The further we let them fall, the heavier they are to pick up” (Field Staff).

“We need to educate the donor” (Field Staff).

Cash transfers work.

Cash transfers effectively empower vulnerable households struggling with the negative impacts of protracted, slow onset crises. They give the people a lift to tackle underlying vulnerabilities. At least this is what a recent Linking Preparedness Resilience and Response (LPRR) case study in Korogocho has highlighted.

So why is it so hard to find funding for them?

This is a question being asked not just by the LPRR consortium but the entire humanitarian sector. More importantly what do donors need from us to increase the likelihood of these programmes being funded?

LPRR is a START Disaster and Emergency Preparedness Programme (DEPP) Department for International Development (DfID) funded 3 year, consortium led project which is aimed at strengthening humanitarian programming for more resilient communities.

The consortium is led by Christian Aid and includes Action Aid, Concern Worldwide, Help Age, Kings College London, Muslim Aid, Oxfam, Saferworld and World Vision. The countries of focus include Kenya, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Democratic Republic Congo, Colombia, Indonesia and the Philippines and cover a multi-risk profile

Case Study

On the 28th February 2016 the LPRR team headed out to Nairobi to explore a joint intervention implemented by two of the consortia member agencies in Nairobi’s Korogocho informal settlement.

The aim was to critically analyse how resilience building could have been integrated into the response intervention, what lessons we can learn from it, what challenges stood in the way and what strengths and successes could be replicated in the future.

This trip makes up case study number three out of eight interventions being researched for the #LPRR project.

Korogocho & the Crises

“Sometimes it feels like hell on earth here, every day we battle to find work” (Community Member)

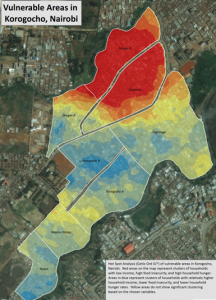

Approximately 200, 000 people live in Korogocho; an area of 1km squared. Life is tough here. A research project called IDSUE (Development for the Surveillance of Urban Emergencies) conducted by one of the LPRR organisations in early 2014 showed that conditions in Korogocho were rapidly deteriorating.

Residents of Korogocho were facing chronic food insecurity, malnourishment and related negative coping mechanisms such a higher amount of school drops outs, and higher prostitution and crime rates. The situation was described by participants as a ‘national disgrace’.

The Intervention

In direct response to this, two of the LPRR consortia member organisations decided that a response intervention had to be implemented. However, they were unable to secure international or institutional funding and so forced to mobilise as much of their own internal, unrestricted funding as possible.

Following a previous urban cash transfer program implemented here, the project utilized the mobile M Pesa system and worked with Safari-com to transfer 2000 Kenyan Shillings per month for four months to 200 of the most vulnerable and marginalized households.

What does resilience mean to you?

One of the aims of this research is to ask community members what resilience mans to them. It has become clear ones perception of resilience is dependent on the context in which they live and subjective to individual vulnerabilities and needs. For the residents of Korogocho resilience means employment and reliable livelihoods.

“Resilience means a job. It means secure employment and knowing where your next meal is going to come from” (Community member)

“If there were jobs and income for all of us then life would be okay and we could sort ourselves out” (Community member)

Success

“People had their eyes opened. They had a taste of what they could do and the life they could live. It gave us hope, that someone cared about us, valued us and believed in us, it still keeps us going today. Next time we would do even better with the support” (Community Member).

The project was hugely successful in tackling immediate needs, alleviating underlying issues and vulnerabilities and creating a higher standard of living in Korogocho. Household interviews and community discussions explained that not only did food insecurity and malnourishment drop but so did the levels of school drop outs, prostitution and violent crime. As soon as basic food needs could be met, health and wellbeing increased, crime rates declined and quality of life improved.

However after the four month project finished the situation gradually began to decline again.

The Challenges

Urban crises are extremely challenging, dynamic, ever changing contexts to work in. Field staff explained that it takes innovation, flexibility and creativity to work in these contexts. All of which the intervention, local partners and community leaders demonstrated.

Furthermore whilst participants clearly outlined that the project had been successful in meeting crucial food security needs and tackling subsequent negative coping strategies; the project timeframe was too short to make a long lasting and sustainable impact.

Once the project finished the situation began to decline again

Furthermore a number of additional challenges were identified:

- The lack of funding available for urban projects

- The levels of insecurity in the area

- The high population density

- The inability to work through local government

- The overwhelming level of need

- The lack of land rights

The Strengths

However despite these challenges the project showed some significant strengths and a clear opportunity for longer term resilience building.

The projects strengths included:

- The high level of participation on the implementation of the project

- The capacity of the elders and existing community leadership system that was in place

- Working through the local partner

All of which enabled a high level of trust to be developed between the community and partner prior to the crises. Furthermore a strong understanding of the risks, power dynamics and structures in place and an understanding of how to utilise these to strengthen the intervention were also highlighted as significant project strengths.

Ultimately it was found that working through the community elders’ leadership model enabled participation, empowerment, and integration of local knowledge and strengthening of community cohesion to be included in the response.

Recommendations from Korogocho

In light of this, the residents of Korogocho and the project field staff highlighted 8 core recommendations for implementing response projects that can incorporate and lead onto resilience building initiatives.

In light of this, the residents of Korogocho and the project field staff highlighted 8 core recommendations for implementing response projects that can incorporate and lead onto resilience building initiatives.

- Use cash transfers to empower the people, make them feel valued and capable

- Educate the donor to fund longer 2-3 year projects in urban, protracted slow onset crises contexts.

- Integrate livelihoods capacity building into the project for sustainability and empowerment

- Work with and through local partners and existing community leadership structures. Engage community leaders in a high level of participation and integrate local knowledge to support with security, beneficiary selection and community mobilisation.

- Work with and through the government from the offset

- Communicate clearly with the whole community throughout all stages of the project so that they know what to expect and why things are happening

- Help households develop hope and a vision for the future

- Develop and implement a well-planned exit strategy

So, tell us – why are donors so reluctant to fund urban, protracted crises interventions? How do we advocate for this to change?

“It worked so why can’t we find funding to continue the project?” (Field staff)

Next Steps

Next the LPRR team will be heading out to Indonesia to explore the Tsunami response and impact 12 years on….

For more information on the LPRR project and to read the full reports or policy briefs please contact Becky Murphy at rmurphy@christian-aid.org

Images: ©Rebecca Murphy