The four speakers at the King’s Climate event ‘Governing Climate after Paris’ on 24 February presented their perspectives on the outcome of the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties in Paris, 2015. They touched upon different aspects of the negotiations but the 2 °C temperature limit articulated in Article 2 formed the underlying theme of discussion. The following areas of interest subsequently emerged:

- The political role of temperature targets

- Framing, and the significance of textual ambiguity

- Pluralism and collaborative effort

- The passing of the superhero narrative

- The question of development

The Paris Agreement is no stranger to the charge of vagueness, or as one of the speakers stated, to the characteristic of ‘constructive ambiguity’. This permits the concerned parties to expand their timelines for implementation, while also functions as an exercise in framing, and demonstrations of the performance of power.

In contrast to the thematic ambiguity of the document, the temperature targets are (relatively; what does ‘well below’ mean?) clear and concrete. Yet they too are problematic and contested. They may have been adopted by the world’s governments, but are they feasible? The near-impossibility of achieving either target is confirmed by energy-economic modelling: simulation studies have to rely on the benefits of yet to be engineered ‘negative emissions’ technologies to even get close. The world appears poised to come up well short of its 1.5°C or even 2°C target.

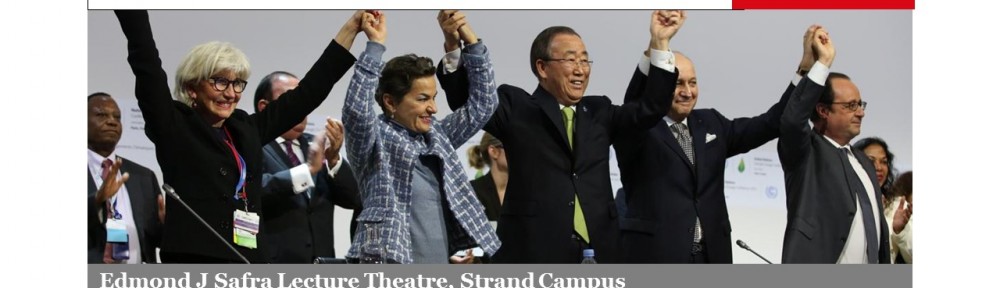

The celebration that followed the Paris negotiations created an atmosphere of anticipation. Politically, temperature targets function as devices of legitimation, creating ways for responsibility to be claimed and adopted by politicians. Their subsequent incorporation into political storylines has not been a matter of uncritical acceptance. A plural approach to the phenomenon of climate change is perhaps rather what is needed. Pluralist interpretations also create a space for the constructive engagement of different actors who are always ‘located’ and/or ‘situated’. They validate different ways of seeing.

The portrayal of climate change as a collective action problem has, in the past, led to the endorsement of top-down approaches to climate governance. A prominent outcome of the Paris Conference, however, was the emphasis on collaborative effort of the bottom-up type. It extends the responsibility of climate governance to parties external to national governments.

Political imagination and broad civic collaboration were recognised as integral to future action on climate change. And the Paris Agreement allows for this. In so doing, it undermines the superhero narrative of climate salvation, whether that be the UN, a legal treaty or silver-bullet technologies. The message is clear: the notion of a single solution and the actor-hero is misplaced.

Responses to the phenomenon of climate change are often conflated with objectives of sustainable development, justice and equality. Climate governance thus ultimately serves a key instrumental purpose – as a means to other ends. And the Paris Agreement gives scope for this creative utilisation of the idea of climate change.

Concluding Remarks:

- The panel recognised that despite action at both the highest and lowest levels of governance, political action in the ‘messy middle’ was limited.

- A re-engagement with political possibilities, imagination and existing tools is imperative.

- Additionally, the panel distinguished between the notion of a ‘solution’ and that of a ‘resolution’. Paris was about the resolution to enact change, not about the implementation of a solution.

- A multiplicity of sites and stakeholders invested in the causes and responses to climate change calls for a pluralistic approach to climate governance and the recognition of local knowledge.

- The panel believed that the Paris temperature targets serve a primarily symbolic purpose; they continue the tradition of aspirational targets adopted by the United Nations.

- It is important at all times to be aware of the impossibility of delivering targets of this kind, while simultaneously recognising the importance of action.

- Viewed in the context of sovereignty, the negotiations and final agreement may be interpreted as signifying the ‘return of the state’, but this is a matter that is open to interpretation.

Finally, and as expressed by one of the speakers, “Paris is better than we expected, but not enough”. COP22 at Marrakesh later this year will continue the climate change story.

Blog by Ramya Kannabiran Tella

Year I, MPhil/PhD Geography

Governing Climate After the Paris Agreement took place on 24 February 2016

The event hosted by King’s Climate was chaired by Professor Mike Hulme.

The speakers were:

• Dr Oliver Geden, Head of EU/Europe Research Division, SWP (German Institute for International and Security Affairs)

• Professor Harriet Bulkeley, Professor of Geography, University of Durham

• Dr Eva Lövbrand, Associate Professor, Department of Thematic Studies: Environmental Change, Linköping University, Sweden

• Professor Mark Pelling, Professor of Geography, King’s College London.