Peter Littlejohns, deputy director of the CLAHRC and public health theme lead, reflects on the ethics of disinvestment, and whether they should be seen as separate from the ethics of investment.

“Ethics” workshops appear to be like buses – they never seem to come and then two arrive at once. My blog last month described a workshop addressing the ethics of improvement science.

This month Gry Wester, Catherine Max and Vicki Charlton of the King’s College London / UCL Social Values group organised a workshop on the ethics of disinvestment. I have blogged about this tricky issue before. While social scientists have always said that “taking something away from someone is different to having not given them it in the first place”, do ethicists concur?

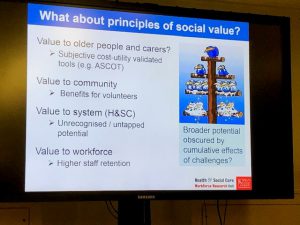

While most people agree that disinvesting is difficult, the day started with Jill Manthorpe, Professor of Social Work at King’s College London, describing how day centres bucked the trend and were de-commissioned (inappropriately so) with remarkable haste. Discussion centred on whether social care was different from health or merely that social care was in an even bigger financial crisis than health (councils have lost 50% of their budget since the crash and some are on the verge of bankruptcy. There is also an issue of how to measure costs and benefits and Jill raised the challenge of measuring social value.

The next two speakers explored international approaches to disinvestment (Janet Bouttell – University of Glasgow) and how English CCGs have approached the challenge (lestyn Williams – University of Birmingham). Both suggested that the efforts have been greater than the results. The final speaker of the morning Scott Greer (from Michigan University, USA, but currently visiting LSE) highlighted his research on how systems approach disinvestment. With the catchy title of “Change for, with or against the public: three logics for service redesign in the UK“) he described how these challenges are faced in England, Wales and Scotland. He concluded there were three logic models of change, and that we should not be surprised how difficult it is to bring about major change, but we should identify some pitfalls to avoid.

After lunch the next set of speakers (Mark Sheehan (University of Oxford) and James Wilson (UCL) addressed the specific question of whether disinvestment raises unique ethical issues or whether they are similar to those of bringing new interventions into the health service. They debated the concept of “ethical equivalence” and its application to “grandfather clauses” in NICE guidance. Judging by the level of delegate discussion, this debate, particularly with James introducing the concept of “reasonable expectations” is to be continued – I feel another thought paper coming on. The day concluded with a “real” commissioner Jim McManus, Director of Public Health from Hertfordshire County Council, describing the dilemma of stopping services on a day-to-day basis.

So what did I get from the day? Well I think that my starting position that disinvestment should not be treated differently from investment, and that they are paired aspects of a single prioritisation process still stands. Over the years I have been involved in three major initiatives to mainstream disinvestment activities. I was a part of group informing the initial Australian attempt – the Astute Project:

- Identifying existing health care services that do not provide value for money.

- The ASTUTE Health study protocol: deliberative stakeholder engagements to inform implementation approaches to healthcare disinvestment.

- Disinvestment policy and the public funding of assisted reproductive technologies: outcomes of deliberative engagements with three key stakeholder groups.

I also worked with a Canadian group – who decided to coin a new name “technology reassessment”: Health technology reassessment: the art of the possible.

And, of course, during my time at NICE, when I was responsible for NICE’s attempt to support disinvestment. These included working with the Cochrane Collaboration Reducing ineffective practice: challenges in identifying low-value health care using Cochrane systematic reviews and developing the NICE “do not dos” within the guideline programme: Disinvestment from low value clinical interventions: NICEly done?

I still need to be convinced that disinvestment (or whatever the current favoured word is) should be considered a separate activity, and not part of guidance development at an individual level and prioritisation and commissioning at a regional and national level.

Setting up programmes to concentrate on “taking away” just galvanises the losers. It will be interesting to see if the latest NHS England approach has more success. See: Sarah Markham: Evidence-Based Interventions Programme—quality improvement via evidence efficacy.

However, the issue will not go away as commissioners faced with increasing demands and limited resources continue to make controversial commissioning (and decommissioning) decisions to balance the NHS books. The latest controversy being around the variation in the decommissioning of cataract surgery.

The workshop concluded with a series of questions that need answering:

- What kind and quantity of evidence should inform disinvestment decisions?

- Are there ‘reasonable expectations’ with respect to ongoing service provision which should inform disinvestment decisions, and are these proprietary to health and social care?

- What is the pertinence of psychological and emotional factors, such as feelings of loss or regret?

- Is there an ethical core to ‘good commissioning’ and should this, by definition, embrace good decommissioning?

- Whose ethics are we talking about? Policy makers, commissioners, providers, end users?

If you are interested in joining this conversation, please contact Gry Wester.

Leave a Reply