The guest post below is written by King’s Water alum Barnaby Dye, who earned an MA in Environment and Development from the Department of Geography last year. In it, Barnaby reflects on his learning and engagement with the Water Security 2015 Conference held at the University of Oxford in December.

Water Security as a concept, invokes many definitions, from those focusing on basic human needs, to ideas of adaptation, to others of disaster prevention. It is also a core concept behind a recently created partnership between the University of Oxford, OECD and Global Water Partnership that aims to study the relationship between this concept and ideas of prosperity, growth and poverty. The project draws on a report proving a causal relationship between these factors and water security. It builds on a conceptual thought experiment, backed up by correlational analyses as well as econometric tests. The results show that there are significant relationships between water insecure areas, defined as areas with high variability of water runoff, and low levels of GDP. Water runoff in simplistic terms meaning the amount of water flowing over surfaces, primarily in rivers. This relationship is further exemplified through analyses of poor countries whose GDP tracks rainfall data and that a range of poor human development statistics are concentrated in these same supposedly water-insecure states.

As partly admitted by the study, what these results could actually be argued to show is the vulnerability of having an economy that is heavily dependent on agriculture, particularly one in a more arid climate. Furthermore, a more structuralist perspective on global economic trends, one that took in factors of history, politics and the unequal market barriers faced by primary producers, might avoid such assertions that verge on the environmentally deterministic idea of a country’s location being the primary reason for its poverty.

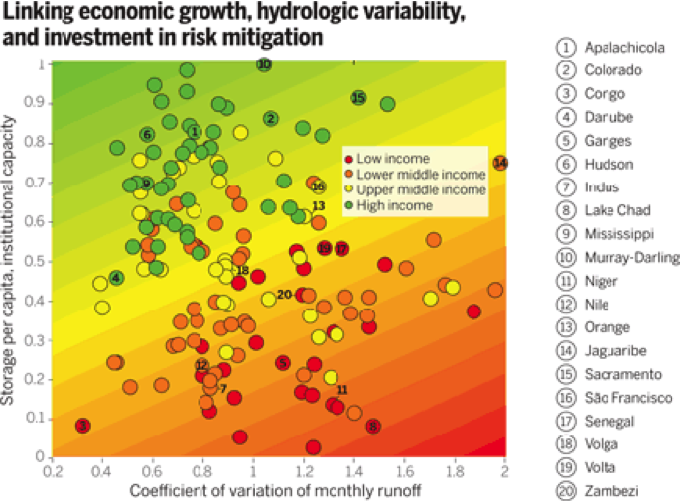

However, leaving that aside, the study proceeds with its conceptualisation of the causal link between water insecurity and poverty being related to quantities of water infrastructure. Such infrastructure is argued to end water insecurity by reducing water variability, thus breaking the ‘poverty trap’ and allowing sustainable growth with help from its irrigation, flood prevention and hydropower benefits. In order to become a good water-secure state then, one would have to see water as a resource to be utilised, a thing to be controlled for the good of society. A good state would want to make water legible then, understood, controlled and managed. The study indicates this would take the form of the ‘three Is’: Institutions, Infrastructure and Information. Through this water-legibility, water rainfalls can be better known, and most crucially, their flows influenced, so that economically productive activities can consistently take place. The relationship is crystallised in this graph which is supposed to show decreased variability and increased infrastructure are correlated with wealth. However, the lack of correlation and presence of middle income countries throughout the graph arguably suggests that water variability is not related to wealth but that merely richer countries have more infrastructure.

The outcome of this water security logic for states might resemble the thesis of James Scott, in that it would adopt modernist rationales of a state ordering society and the environment. A water-security conscious state would similarly seek to ‘read’ and govern water, shaping it to its preferred idea of what a society and its environment should embody. This would happen through the measuring of water by ‘rational’ scientists who would then design a benign set of infrastructures transforming the wild and irrational variable flow of water into a tamed, known and ‘productive’ one; more infrastructure and less variability is seen as an essential good. Such water security thinking seems to be based on inherently modernist principals. The first is that that a scientifically ordered environment of constant water flow is superior to presently existing irrational and unproductive variable flows. This ignores the socio-environmental systems and services inherently based upon water variability. Principally these might involve the fertilising and irrigating annual floods which underpin many agricultural systems and aquatic ecosystems (including riverine and coastal fisheries). An example that springs to mind here being the Rufiji in Tanzania, which is one of the country’s most productive farmland areas that also contains a significantly biodiverse mangrove swamp. The second is that it seems to presume that economically productive activities involve a farming system of predictable and managed irrigation. This can be argued to be markedly Eurocentric, favouring the agricultural systems of the ‘North’ that are premised on all year water, and modernist, in that it preferences scientifically-produced and technology-intensive agriculture without considering the merits of existing systems.

The outcome of this water security logic for states might resemble the thesis of James Scott, in that it would adopt modernist rationales of a state ordering society and the environment. A water-security conscious state would similarly seek to ‘read’ and govern water, shaping it to its preferred idea of what a society and its environment should embody. This would happen through the measuring of water by ‘rational’ scientists who would then design a benign set of infrastructures transforming the wild and irrational variable flow of water into a tamed, known and ‘productive’ one; more infrastructure and less variability is seen as an essential good. Such water security thinking seems to be based on inherently modernist principals. The first is that that a scientifically ordered environment of constant water flow is superior to presently existing irrational and unproductive variable flows. This ignores the socio-environmental systems and services inherently based upon water variability. Principally these might involve the fertilising and irrigating annual floods which underpin many agricultural systems and aquatic ecosystems (including riverine and coastal fisheries). An example that springs to mind here being the Rufiji in Tanzania, which is one of the country’s most productive farmland areas that also contains a significantly biodiverse mangrove swamp. The second is that it seems to presume that economically productive activities involve a farming system of predictable and managed irrigation. This can be argued to be markedly Eurocentric, favouring the agricultural systems of the ‘North’ that are premised on all year water, and modernist, in that it preferences scientifically-produced and technology-intensive agriculture without considering the merits of existing systems.

By removing the under-pinners of an existing socio-environmental system, this water security definition around variability and infrastructure could lead to States creating numerous dis-benefits that could lead many into less economically and water-secure lives. This argument is made not to dismiss the challenges that are presented by variability. Indeed they do not dismiss the idea that dam-infrastructure or other large scale interventions should never be considered. However, they do point to the fact that whilst necessarily fluid and less controllable, flooding can nonetheless be crucially beneficial. A narrow understanding of water security can consequently be argued to provide a justification for large infrastructure adhering to essentially modernist and statist agendas that ignore the values of existing agri-environmental systems and the people affected by such interventions. This point is perhaps most illustrated in the report’s stating of the benefits of water-security technology and infrastructure (read dams) without listing the comparable costs these infrastructure entail. A growing body of critical dam-literature[i] focuses not only on displacement of people but also the loss of agricultural income, ecosystems and on dam-made earthquakes and flooding. Such a glaring omission begs the question, who is ‘water security’ being created for?

A further question asked by this analysis of the water security agenda is how it should relate to the ‘small water’ agenda of hygiene and drinking water. Large infrastructure projects reducing variability may well be able to deliver tangible benefits in this area, but through the changes wrought by them, they can also endanger the flows that deliver ‘WASH’ (Water and Sanitation Hygiene) solutions.

Fundamentally it is important to think about whether water security means intervening in the environment to reduce variability and increase reliability, or whether it might entail accepting the challenges presented by extremes of water and building the physical ‘hard’ and more important ‘soft’ socio-cultural and aversion systems that allow people to adapt and live through them. Should we seek to impose solutions of universal increased infrastructure or base solutions on the knowledges, existing agri-environmental systems and participation of those trying to achieve water security?

The REACH program which has been recently launched in Oxford offers an exciting opportunity to tackle these issues in its aim to deliver ‘water security’ to 5 million people across three countries with the closer marrying of development practise and academia. And indeed many of the distributional, gendered and power related aspects were discussed at the Water Security Conference that took place in Oxford to launch the program in December. Crucially, discussion in the conference recognised that ideas of water security vary at different scales, going beyond the idea of mere water runoff to think about what it means for individuals, communities or regions. It is therefore hoped that REACH will engage in these fundamental questions, creating a broad, critical and policy-relevant idea of water security at its base for implementing a water security agenda.

[i] To name the most prominent: Reisner, 1986; Adams, 1991; McCully, 2001; Khagram, 2004; Scudder, 2005; Everard, 2013; Ansar et.al. 2014,