The medical books, pamphlets and periodicals held in the Foyle Special Collections Library reflect the rich tradition of medical teaching and research across King’s Health Partners. Many of these items have significant provenances relating to medical figures who have worked for, or been connected with King’s.

The medical books, pamphlets and periodicals held in the Foyle Special Collections Library reflect the rich tradition of medical teaching and research across King’s Health Partners. Many of these items have significant provenances relating to medical figures who have worked for, or been connected with King’s.

In this article, Brandon High, Special Collections Officer discusses some of these that he has noted in his recent cataloguing.

A 1716 treatise on the eye, written in Latin and entitled Tractatus de circulari humorum motum in oculis, is part of the St. Thomas’s Historical Collection and bears the inscription of the physician and popular versifier Nathaniel Cotton (1705-88). His principal claim to fame is that he looked after the poet William Cowper (1731-1800) for two years in his private asylum during one of Cowper’s bouts of mental illness. Cotton’s treatment was apparently successful, as the regime in his asylum was humane, unlike the practices of some of the more notorious privately-owned ‘madhouses’ of that era. There are four other books in the historical medical collections with Cotton’s bookplate or inscription.

Other provenances in the historical medical collections with literary connections include the collection of books with the inscription of the St. Thomas’s surgeon and King’s professor of surgery Joseph Henry Green (1791-1863). Green was a close friend of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and was his amanuensis for several of his prose works. Joseph Henry Green’s ideas on the role of medical practitioners in society paralleled those of Coleridge on intellectuals, and both agreed on the importance for social and political order of higher education institutions (like King’s) with strong connections to the Anglican Church.

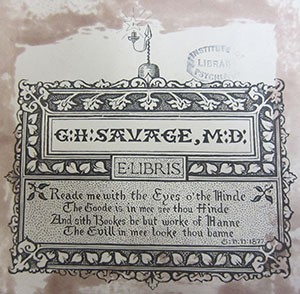

A number of books which bear the bookplate of the psychiatrist George Henry Savage (1842-1921) are now in the Institute of Psychiatry Historical Collection at the Foyle Special Collections Library. Savage was one of Virginia Woolf’s doctors during her frequent periods of mental distress, and was very unfavourably portrayed as the psychiatrist Sir William Bradshaw in her landmark modernist novel Mrs. Dalloway (1925), who lamentably fails in his duty of care for Septimus Warren Smith, a veteran of the First World War.

A number of books which bear the bookplate of the psychiatrist George Henry Savage (1842-1921) are now in the Institute of Psychiatry Historical Collection at the Foyle Special Collections Library. Savage was one of Virginia Woolf’s doctors during her frequent periods of mental distress, and was very unfavourably portrayed as the psychiatrist Sir William Bradshaw in her landmark modernist novel Mrs. Dalloway (1925), who lamentably fails in his duty of care for Septimus Warren Smith, a veteran of the First World War.

The St. Thomas’s Historical Collection also includes a limited edition copy of W. Somerset Maugham’s first novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897), published to mark the fiftieth anniversary of its first publication. This novel is heavily based on Maugham’s experiences as a St. Thomas’s medical student, caring for pregnant women. He qualified as a medical practitioner, but never practised.

All these provenances can be searched on the King’s Library catalogue using the drop down menu and selecting the ‘Former owners, Provenance’ search option, and typing the name of the relevant person

You can also read detailed guides to the medical collections and other Special Collections Special Collections homepage